Australia’s distributed energy networks, normally seen as little more than the local poles and wires that deliver electricity to homes and businesses, have made a pitch to play a greater role in the green energy transition, including soaking up and sharing solar, and installing more storage and EV chargers.

The pitch comes in the form of a new report from the network lobby group, Energy Networks Australia, called “Getting smarter with the Grid” that has been released this week.

Its basic premise is that the opportunities within local networks have been largely ignored in the push for large scale projects and big transmission lines, but it has a lot to offer in creating local energy hubs and excess capacity that can be used for wind, solar and storage projects.

“The distribution grid is under-utilised,” says Dom van den Berg, the CEO of the ENA. “It can do more of the heavy lifting.”

That would make sense, if only because the cost of local networks are the biggest part of most consumer bills, accounting for nearly half of costs.

Part of that is because of the sheer size of the country, and the networks, but it is also partly due to the infamous “gold plating” of the networks that occurred more than a decade ago when local grids were upsized for demand that never materialised.

Now, with the shift to electrification, and EVs and other electric appliances, and the need for local storage, it’s time to actually use that capacity.

There’s only one problem – many of the proposals made by the local network companies, such as sharing solar, battery storage, and providing public EV chargers – are currently outside their remit.

The way that the Australian electricity market is regulated means that the networks have been prevented from investing in or owning anything that looks like generation or storage. And many of the regulations are yet to catch up with the technology.

The networks have been trying for years to break down some of those barriers, and figure that the economic benefits in this plan is a new opportunity. But there is no doubt that the big generators and “gentailers” that dominate that side of the market, and protect it fiercely, and will suspect or fear a Trojan horse, and potentially stand in their way.

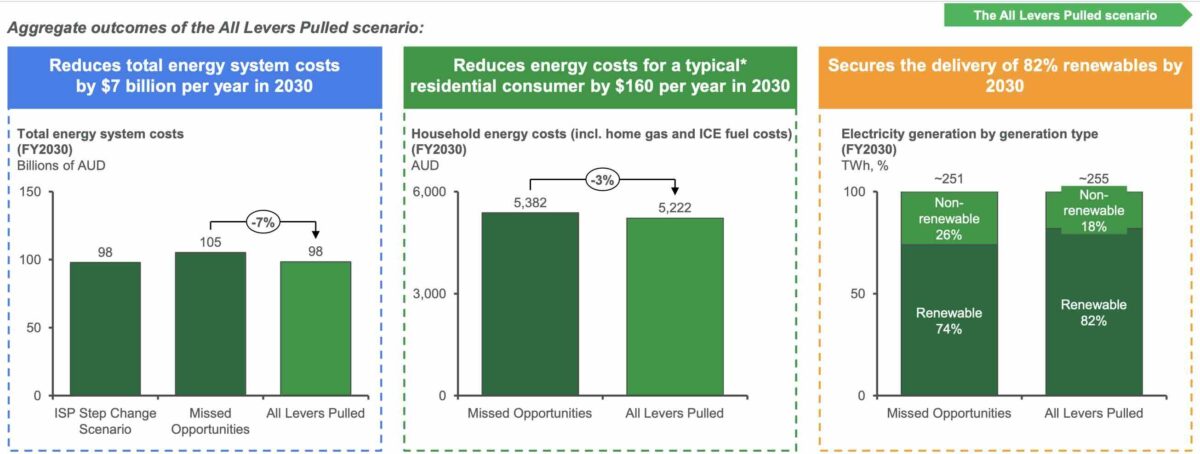

The ENA estimates that the changes outlined in its report could save around $160 a year per consumer and would collectively avoid $7 billion in overall system costs by 2030. And it says they will be crucial to help Australia reach its now very ambitious target of 82 per cent renewables by 2030. It might not get there on time without it.

The proposal includes a number of initiatives that are impossible under the current regulatory environment, either because networks are not allowed to be involved, or because the right incentives simply do not exist.

Among these proposed changes are the ability for networks to plug in more EV charging infrastructure, which currently do not come under their regulatory remit, and to allow them to share storage with third parties, which is currently also not allowed, and which would enable them to help soak up more solar.

“Current regulation prevents DNSPs from sharing battery capacity with third parties that participate in wholesale

electricity markets, with all current pilots and programs only possible under limited waivers,” the report notes.

“A holistic and long-term solution is needed. Current network investment regulations do not properly value the time-shifting ability of batteries to increase the value of a customer’s solar output by absorbing it during the day and re-exporting it during the peak.”

Other initiatives include having a good look at local networks for the creation of local energy hubs – as is occurring in Queensland, where the networks are still government owned – rather than focusing only on transmission based renewable energy zones.

The report also recommends introducing incentives for larger rooftop solar systems – particularly for businesses, which the networks say they can help connect quickly – and getting consistency on connection policies, rules around flexible devices, and getting better and consistent standards on all behind the meter devices.

And the networks want changes to the current five-year regulatory cycle, which they say is unwieldy, and they also want local network considerations to be included in the next Integrated System Plan, the long term blueprint delivered every two years by the Australian Energy Market Operator.

“There needs to be a flow of technical information on grid status, as well as price signals, between parties,” it says.

“There is a lack of technical standards and many devices currently on the market lack the capability to receive coordination signals. Changes to customer tariffs and connection agreements are difficult to make within a

five-year regulatory period, which limits the ability of DNSPs to provide economic signals to customers.”

The ENA reckons that with the right policy and regulatory settings it could unlock at least 5 GW of

additional rooftop solar, 7 GW of additional front-of-meter generation by 2030 and 5 GW of additional distribution-connected battery storage, and enable at least 4 million EV’s on the road by 2030.

“The time is now to change the way we think of the distribution grid, what we ask of it and the types of services it can provide customers,” it says.