Batteries come in different sizes and their owners are motivated to install them by different factors. Each ownership model has implications for the income streams that it can access.

The business case for each battery category (big, mid, and small) depends not only on the capital cost but also on how the battery is operated and the income streams that can be accessed. Batteries can help stabilise the power grid, reduce power costs for households, and help reach our renewable energy targets.

Battery business model

Different battery business models are emerging. The technology has the potential to dominate the trade in demand flexibility at all market levels and disrupt the National Energy Market (NEM), including the frequency and ancillary services market.

The battery business model needs to be understood from the perspective of ownership and connection point, the customer base, and how and to whom the revenue accrues.

The NEM rules define who can access value, which has revenue consequences for each of the battery ownership models. Each of these ownership models has implications for how capital costs can be recovered and how value can be shared.

Each ownership model impacts electricity bill affordability differently and how the battery owner is positioned in the market will also define how costs are passed on to the end consumer.

Big Batteries connected to the transmission level are predominantly owned by third parties and operated for profit. They earn income from energy arbitrage (buy low and sell high) and power system (frequency) support.

Small household batteries are located behind the meter and owned by the end consumer. They earn income from electricity bill savings by energy banking, shifting demand, and maximising self-consumption from rooftop solar.

Mid-scale batteries are in front of the meter and connected to the distribution network and can power about twenty houses.

The options of ownership are third-party owned and operated for either profit or for the benefit of the community. Third parties such as a local government, Aggregators or Virtual Power Plant (VPP) operators. Otherwise, they can be owned by the distribution network (DNSP) and operated for profit as a ‘Network Support Battery’.

Current market rules in competition with consumers

The technical beauty of batteries is they can provide multiple power system services at once. They can provide active network management, allow for more solar to be hosted on the grid, intra-day shifting of energy.

The challenge for energy market reform bodies is to amend the NEM rules and develop tariffs that value the full value stack that ‘Community Batteries’ can offer.

There is an ambit claim by DNSPs to own and operate all ‘Community Batteries’ and restrict third party access to the grid. Efforts by DNSPs to control the operation by third party owners of a mid-scale battery has big implications to the operation of the market and electricity bill affordability.

Under current NEM rules the DNSP has the potential to not just double dip but quadruple dip. That is access to taxpayer funding to pay for the capital cost of the battery, benefit from the use of it and operate it for profit, include it in their Regulated Asset Base to derive an annual dividend for the life of the assets, and finally charge for it through electricity bills.

As regulated monopolies, the market bodies oversee and seek to manage DNSPs’ structural advantages that would otherwise allow them to dominate the market.

However, without changing the NEM rules firstly around the DNSP current business model and secondly to allow third party ownership of ‘Community Batteries’, the DNSPs will compound the current situation of super profits as monopoly power networks exploit system failures and will fail to deliver value for energy consumers, or reduce bills.

Network storage tariff

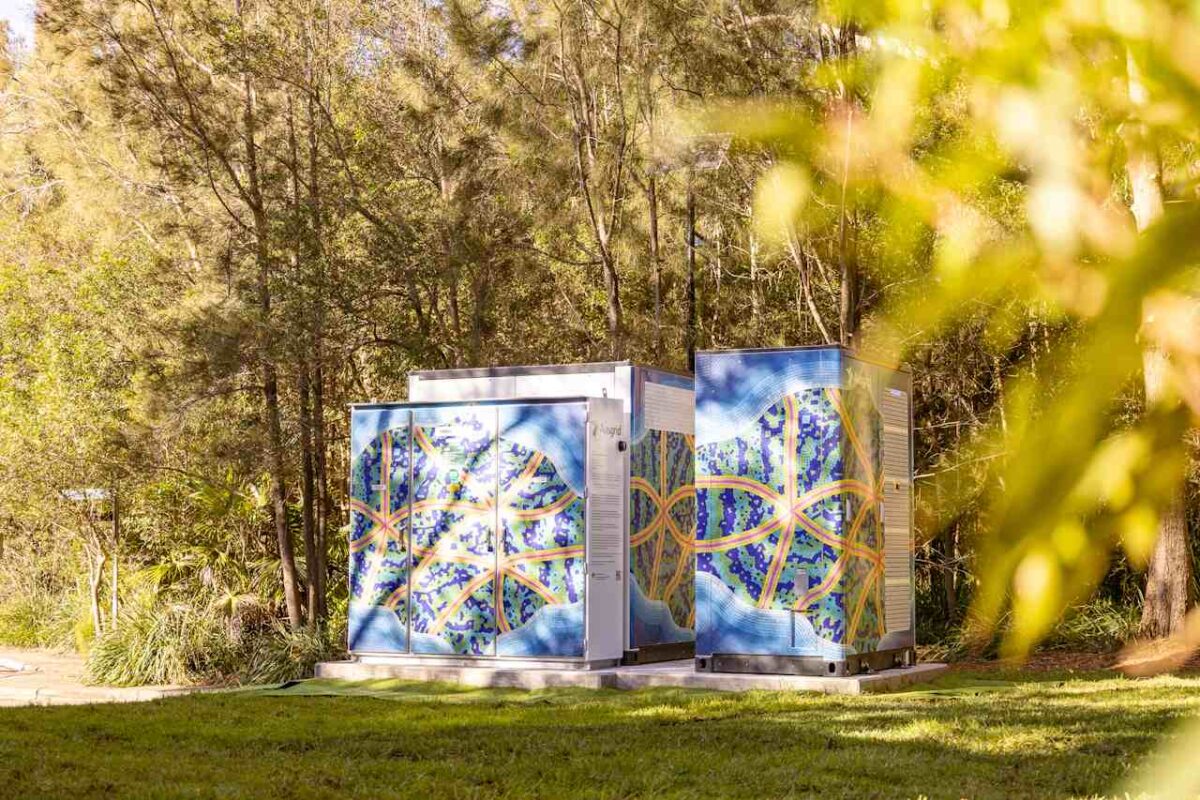

This situation is playing out in Noosa, where the Shire Council, with support from the community group Zero Emissions Noosa, successfully received an Australian government grant for a Community Battery.

The Noosa battery is anticipated to deliver a battery twice the size at a comparable cost to the less cost-effective Energy Queensland batteries. The Noosa Shire Council battery will provide network services and additional services to their community.

However, Energy Queensland’s recent move to introduce a Storage Network Tariff of $6,500 per year is argued to be anti-competitive. It is not tied to a service. It is much higher than any charged by any other DNSPs across Australia. It applies to non-Energy Queensland batteries only and significantly impacts the financial viability of third-party-operated batteries.

Furthermore, the DNSP has a financial incentive to purchase services from its own batteries and no regulatory obligation to purchase services from third-party-owned batteries and even from its own customers.

Allowing such a ‘battery storage tariff’ will penalise new market participants, and will increase electricity bill costs to households and businesses.

Future system operation

Many have questioned the ability of the current market arrangements to deliver the clean energy transition at the lowest cost to the consumer.

As the Integrated System Plan document outlines, by 2035, there will be a need for 33 GW / 514 GWh, or a twelvefold increase in capacity from today’s levels. Achieving this requires policy and regulatory settings that compensate end consumers for allowing their energy assets (solar, hot water systems, batteries, electric vehicles) to benefit the electricity system.

The options to achieve this is to move toward ‘Demand flexibility Markets’ and ‘Local Electricity Markets’. This will require the break-up of the DNSP to manage market conflicts of interest and the introduction of a Distribution System Operator (DSO). The DSO could then acquire network support and power system support services on a cost-competitive and technology-neutral basis to ensure the operational safety of the distribution network.

Local governments have an important role in operating a future energy system. They are well placed to work with the end consumer to transition to Local Electricity Markets’ operation. They are key to unlocking local economic benefits of aggressive efficient electrification and the roll out of Local-Renewable Energy Zones. They are key to putting ‘Community’ back into ‘Community Batteries’.

Dr Vikki McLeod is Rewiring Australia’s energy market reform – expert adviser