Australia’s main scientific body and the country’s energy market operator have again underlined the fact that “integrated” wind and solar – including the cost of storage and transmission – is still by far the cheapest source of new electricity generation in Australia.

The 2022 version of CSIRO’s annual GenCost report also points to a rapid fall in the cost of hydrogen electrolysers, which will increase hopes that Australian can use its abundant and cheap wind and solar energy to become a global hydrogen and renewable superpower.

The latest GenCost report is important because it emphasises the point that wind and solar, including the cost of storage and transmission, is still by far the cheapest form of generation, even up to a 90 per cent share of total generation.

It also underlines some important principles about a renewables grid. Solar and wind do not require additional investments in storage and transmission until their share of generation reaches around 50 per cent.

Once they do, and even including the added cost of storage and transmission, wind and solar remain the cheapest sources of electricity up to a 90 per cent share, mostly because far less storage is necessary than many people believe.

From levels of around 90 per cent wind and solar, other renewables such as hydro power, biomass and green hydrogen will be required to make the leap to a 100 per cent renewables system.

The GenCost report also makes some other key observations: Cost reductions in widely touted technologies such as carbon capture and storage (CCS), nuclear Small Modular Reactors (SMRs), solar thermal, and ocean energy are lagging and would require stronger investment to realise their full potential.

And, despite intense pressure from the nuclear lobby and many in mainstream media (News Ltd, Nine/Fairfax and others), the CSIRO says the status of nuclear SMR has not changed, and it sees no prospect of projects in Australia this decade, given the technology’s commercial immaturity and high cost.

Worse, the GenCost report says nuclear’s best chance of deployment around the globe is only if the world does not take climate change seriously.

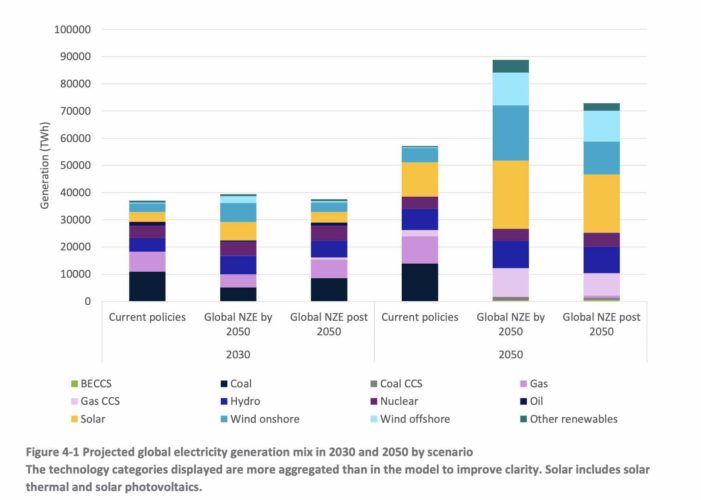

If the world is looking to meet Paris targets of limiting average global warming to 1.5°C, then other technologies will rule because they are cheaper and quicker to deploy and nuclear’s share of generation will diminish significantly. (See table below).

That’s important to note, because the Australian Energy Market Operator’s 30-year blueprint known as the Integrated System Plan assumes a share of renewables of around 80 per cent by 2030, as does the newly elected federal Labor government. All brown coal generators are expected to close by 2032.

CSIRO’s observation that hydrogen electrolysers are experiencing a “rapid” fall in costs, and could accelerate the uptake of green hydrogen, will also encourage many to believe that the likely core scenario of AEMO’s ISP will soon become the “hydrogen superpower” scenario.

That hydrogen superpower scenario assumes an even more rapid switch to renewables – in the high 90 per cent within a decade, and no coal generators in the fleet of any sort.

Another major new aspect of this GenCost report is the ditching of the “diverse technologies” scenario. This echoes the decision by AEMO to dump the “gas led recovery” championed by the previous Coalition government, mainly because virtually no one thought it was plausible or took it seriously.

“Stakeholder feedback received during AEMO’s 2020-21 Australian scenario development process found that it was unlikely that alternative technologies will be able to compete in a significant way with renewables,” the report notes.

“This reflects relatively uncompetitive gas prices, a lack of confidence in the future cost competitiveness of CCS technologies and abundant low-cost renewable resources.

“Some of these concerns about a Diverse technology scenario are specific to Australia’s circumstances. However, there are countries with similar energy resource profiles where the Diverse technology scenario also lacks plausibility. This scenario has been removed.”

However, CSIRO notes that the cost reductions of wind and solar are likely to pause this year because of the supply constraints and higher material costs, but CSIRO says this is difficult to quantify (even though the likes of BNEF have recently pointed to rises of 7 per cent to 14 per cent in average capital costs).

“We don’t have a lot of good evidence for projects that will be built in the next year,” CSIRO’s Paul Graham, the lead author, told RenewEconomy. “It will have to affect projects eventually – so you’d expect no further decreases in real terms next time, it’s just that we don’t know by how much. It might be in line with inflation.”

However, the cost increases next time round for gas and coal may be considerable, particularly because of the sharp increase in commodity prices that have already flowed through to wholesale electricity prices in Australia.

This is where the CSIRO’s estimates get interesting. It puts cost of a renewables-based grid in the low $70s/MWh, including storage and transmission. Even in Western Australia, with an isolated grid with limited options for transmission, the increase is only marginal, to the high $70s/MWh.

Compare that with the prevailing prices of Australia’s still fossil fuel dominated grid, driven by soaring coal and gas prices. Prices have averaged more than $500/MWh in the country’s most fossil fuel dependent grid, Queensland, so far in July.

As the CSIRO notes, lowering emissions goes hand in hand with lowering costs to consumers. It is just unbelievable that the opposite is still being peddled by vested interests and lazy media.

CSIRO also notes the falling costs of offshore wind – further reinforced by the landmark auction held by the UK last week – which will encourage those seeking to develop more than 20GW of osffshore wind projects off the coast of southern Australia, and Victoria and NSW in particular.

“Both onshore and offshore wind costs have fallen faster than expected,” the report says.

“Onshore wind cost changes reflect Australian projects. Offshore wind is yet to be developed in Australia however, cost reductions achieved overseas mean that Australian projects are expected to be lower cost than previously expected.”

Graham says he had expected offshore wind costs to be even lower, but he says it is clear that offshore wind is the “most economic technology after (onshore) wind and solar.”

See also: Why Australia doesn’t need so much storage in a wind and solar grid

And: Slow, expensive and no good for 1.5° target: CSIRO crushes Coalition nuclear fantasy