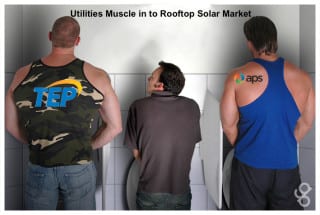

In the past five years, rooftop solar has revealed the limitations of the archaic electric utility business model, as customers have found generating their own power more cost effective than taking 100% of their energy from the incumbent monopoly. For years, utilities have fought back by trying to make competition less cost effective, at a substantial cost to their image (and ratepayer’s own money).

In the past five years, rooftop solar has revealed the limitations of the archaic electric utility business model, as customers have found generating their own power more cost effective than taking 100% of their energy from the incumbent monopoly. For years, utilities have fought back by trying to make competition less cost effective, at a substantial cost to their image (and ratepayer’s own money).

Now they want a piece of the action.

It was only a matter of time until electric monopolies realized that co-opting would be less costly than confronting, and several utility companies are now planning to own solar on their customers’ roofs. Southern Company CEO Tom Fanning put it bluntly, “If distributed generation is eroding your growth, own distributed generation!”

The big question is: Will utility-owned rooftop solar add to or replace customer ownership of solar? And secondarily, is this a good deal for utility customers?

Two Pilot Utility-Owned Rooftop Solar Programs

Tucson Electric Power, based in the sunniest part of the U.S., received regulatory approval for a residential solar program in 2014. The 600 arrays they’ve proposed will average 6 kilowatts. The cost of TEP’s program is estimated at $10 million for a cumulative capacity of up to 3.5 megawatts of solar capacity. The utility says it will be between $2.85 and $3.50 per Watt.

Customers pay a one-time $250 application fee and a monthly fee equivalent to their average utility bill payment over the past 12 months. Customers receive the electricity from the solar array as bill credits, with the system sized to their annual average use. Thus, the only savings for customers will be if utility rates rise (they have by 2.8% per year since 2008).

ILSR’s analysis suggests that it will take customers about 5 years to pay back the program application fee, and that the net benefit to the customer over 25 years will be about $6,800.

Arizona Public Service has also planned a residential solar offering. It’s program will provide 1,500 customers a $30 monthly credit over 20 years, with no upfront fee. The program is anticipated to cost $28.5 million for 10 megawatts of solar, for an average installed cost of $2.85 per Watt.

ILSR’s calculation of net benefit suggests that customers will gain about $5,600 over 25 years from the APS program (adjusted for the time value of money and inflation), with no payback period because the customer has no upfront costs.

Convenient, but Costly to Customers

How do utility-owned residential solar arrays compare to customers owning their own array? Using the National Renewable Energy Laboratory’s System Advisor Model, we find that the cost of energy averaged over 25 years for an APS customer who buys their own system at $3.50 per Watt is just 7.1¢ per kilowatt-hour, with a net present value to the customer of $19,400. A similar array in Tucson would have a levelized cost of energy of 6.9¢ and net value of $14,900. The difference is based on the value of electricity purchases that are avoided, at the different utility rates (other assumptions explained at the end of this piece). The following chart illustrates the substantial difference

Rewarding to Utilities

Although the utility companies argue otherwise, customer ownership of solar is typically a net benefit to the utility. A 2013 study in Arizona suggested that APS would be ahead $34 million from net metering of customer-owned solar in 2015. In other words, the utility-owned solar program makes money for the utility: over $13,000 per solar customer over 25 years, in addition to the already-booked benefits from privately-financed solar added to their grid.

Part of a Plan to Kill Competition

Part of a Plan to Kill Competition

The dollar data is damning enough, but both APS and Tucson Electric Power have been trying to make customer-owned solar less lucrative. APS has asked to quadruple an existing fee on solar customers and the Tucson utility has proposed changing compensation for solar producers that would reduce the average monthly savings for customers by $22.

It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to see what happens when utilities offer their own solar installation program at the same time they are quashing competition.

The Camel’s Nose

Attracted by the opportunity to divert customers from independent ownership and bank more of the revenue from distributed solar, other utilities are also considering offering residential solar services.

On the website of its regulated monopoly arm, Georgia Power encourages visitors to talk with one of their “solar experts.” If the customer chooses to move ahead, Georgia Power Energy Services (an unregulated subsidiary) can provide the solar installation. But if the company uses the website of its regulated business to drive customers to its unregulated affiliate, it may be in violation of state law. So far, Georgia Power’s unregulated arm does not provide financing or a solar lease, though the company hasn’t ruled it out.

CPS Energy, a municipal utility serving San Antonio, TX, has also expressed interest, with a request for proposalreleased this February. It intends to install about 1 MW of solar in a model similar to APS, where the customer is paid a roof rental fee over 15 years, with no access to the solar energy produced on their rooftop. Prices haven’t been released.

The idea of utility-sponsored solar is actually 20 years old, but in Sacramento, the municipal utility saw it as a way to create a vibrant non-utility market, not co-opt it. In fact, a staff person from that utility suggested in an interview earlier this month that utilities looking to own customer-sited solar are “waving the white flag” in their inability to encourage an independent market

Implications

As Sacramento’s experience highlights, there are ways for utilities to aid in the development of a robust distributed solar market. But the utilities moving most quickly toward utility ownership of solar on customer rooftops have a history of fighting customer ownership, and their move into the distributed solar sector seems likely to undermine the opportunity to rapidly deploy rooftop solar and spread its attendant economic benefits.

Source: ILSR. Reproduced with permission.