New prime minister Malcolm Turnbull wants Australians to get excited about the new “disruptive” technologies that are sweeping through the global economy – in energy and transport in particular.

New prime minister Malcolm Turnbull wants Australians to get excited about the new “disruptive” technologies that are sweeping through the global economy – in energy and transport in particular.

If that’s really his goal, then he should be pushing hard on those technologies that can help Australian households generate and store their own power, because they are likely to play a critical role in an energy system that relies heavily on renewables. And that appears inevitable, government policy or not.

Labor has already spoken of its ambition for a 50 per cent renewable energy target by 2030. The Coalition, so far, has refused to look beyond 2020, but it is unimaginable that Turnbull would repeat the Tony Abbott line that the current target, equivalent to around 23.5 per cent of total generation by 2020, is “more than enough”.

In reality, Australia could probably aim a lot higher than 50 per cent even by 2030, given that Tasmania is already at 100 per cent, or near enough, the ACT aims to get there by 2025, South Australia aims to get to 50 per cent by 2025 (but will do so much earlier), and Queensland has a 50 per cent target by 2030.

The conservative governments in Western Australia and NSW have no such targets, but recently WA energy minister Mike Nahan said that within a decade, all daytime demand in the state could be met by rooftop solar, and NSW has spoken enthusiastically, but somewhat opaquely, about being Australia’s equivalent to California.

Investment bank UBS recently produced a report on how a 50 per cent national renewable energy target might be met. It spoke of the need to build around 20,000MW of wind energy, and 26,000MW of solar energy. Most interesting, though, was the critical role that households could play in knitting these technologies together.

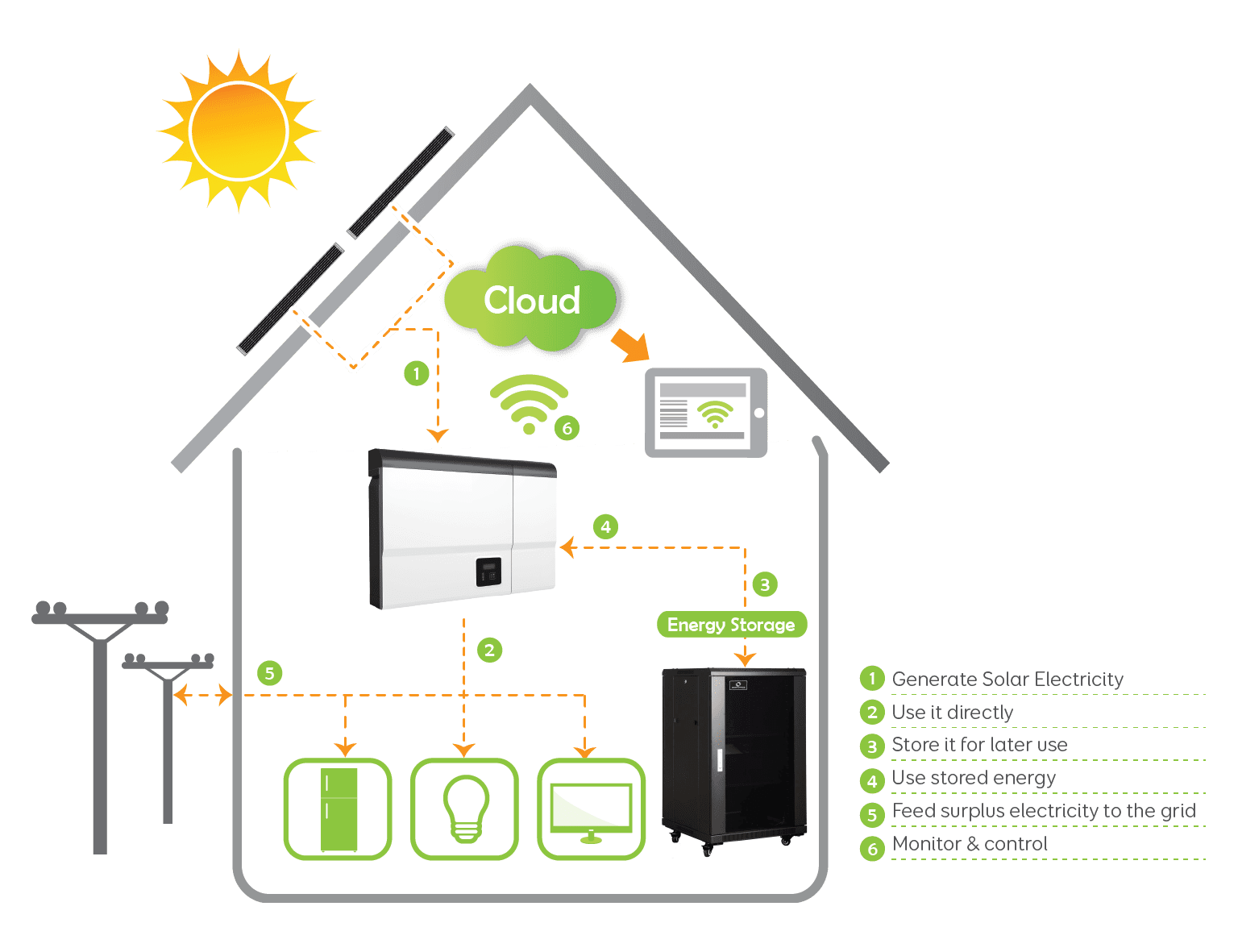

UBS, like other analysts and observers, and some market operators, predicts a massive take-up of solar PV in the coming decade. The number of houses with rooftop solar is expected to jump at least four-fold within the next 10-15 years, and businesses will add solar too. The difference with the last few years is that this will be accompanied by battery storage, which will be delivering attractive paybacks of 5-6 years by 2020, and quite possibly earlier.

In its report, UBS suggests that if one million households – just over 15 per cent of the 6.6 million households in the National Electricity Market (which excludes W.A., the Northern Territory, Mt Isa and the like) – had a battery of around 7kWh, then that would be capable of providing about 2-3GW of power at any given time.

“Household storage and utility storage should be sufficiently economic in 5-6 years to give some confidence that storage will be a “tool” to help deal with the volatility for higher renewable penetration,” it notes.

“Storage also helps to manage the swing in capacity as utility-scale PV output drops in the afternoon and prior to the pickup in wind generation.”

The attraction to this is that much of the investment would come from the households themselves, or it could be an incentive for the retailers and others to come in and provide services.

“Unlike PV, household storage does not need a detached house,” UBS writes. “If utility-scale solar was priced low enough in the middle of the day, we think households would be incentivised to charge the battery in the middle of the day and consume in the evening.”

UBS also notes that having storage widespread in the community does not mean large numbers disconnecting. But it will mean less investment in the grid in terms of peak and largely unused capacity, and more investment in the “intelligence” of the grid.

Some of these ideas are already being pursued. Ergon Energy, the network operator and retailer in regional Queensland, is trialling a “virtual power plant combining the output of 30 homes with solar, storage and smart systems. CSIRO have conducted similar trials.

The idea is to see how the output of the aggregated solar arrays, or their energy stored in batteries, could be used to respond to peaks in demand and manage the network, and reduce the cost of upgrades.

The idea is to see how the output of the aggregated solar arrays, or their energy stored in batteries, could be used to respond to peaks in demand and manage the network, and reduce the cost of upgrades.

One contact who works in network management suggested recently that just 15,000 electric vehicles could potentially be combined to provide up to 300MW of capacity that could respond to demand requirements. The same principle can be applied to battery storage systems in the home.

Imagine that, then. A grid not reliant solely on centralised generation, and those peaking plants that sent up the price of electricity when demand surged on the big summer temperature spikes. Already, solar PV has delayed or even removed many of these spikes. Battery storage could clear them altogether.

This idea of the “decentralised grid” is gaining credence each week in the energy industry. Most see it as inevitable, even big coal fired generators like Engie. The WA and the South Australian markets are expected to meet their daytime demand with rooftop solar only.

The concept of a grid relying mostly on “base load” such as coal or nuclear is rapidly being replaced by a “flexible” energy system. A high renewable grid in Australia would not just mean a lot of wind and solar farms and the like, it would be a system reliant on, and supported by, consumers themselves. And they would get a financial benefit from doing so.

Indeed, this week, head of the main grid operator in the UK said “the idea of baseload power is already outdated”. He said the system needed to be look at the other way round.

“From a consumer’s point of view, baseload is what I am producing myself,” Steve Holliday, CEO of National Grid, told Energy Post in an interview.

“The solar on my rooftop, my heat pump – that’s the baseload. Those are the electrons that are free at the margin. The point is: this is an industry that was based on meeting demand. An extraordinary amount of capital was tied up for an unusual set of circumstances: to ensure supply at any moment.

“This is now turned on its head. The future will be much more driven by availability of supply: by demand side response and management which will enable the market to balance price of supply and of demand. It’s how we balance these things that will determine the future shape of our business.”

That should give Turnbull plenty to think about. One thing we can hope from the new Liberal leader, along with Labor and the Greens, is that having more wind and solar does not mean giving up our lifestyle, as the Luddites on the right and the pro-nuclear lobby would have us believe.

There are a lot of exciting technologies out there, Australia just needs to think smarter about how it implements them.