A new report by the Öko-Institut, commissioned by Greenpeace, shows that unregulated data centre development could serve as a boost for fossil fuels and limit renewable energy development, and that strict new guidelines are required to ensure artificial intelligence doesn’t threaten climate goals.

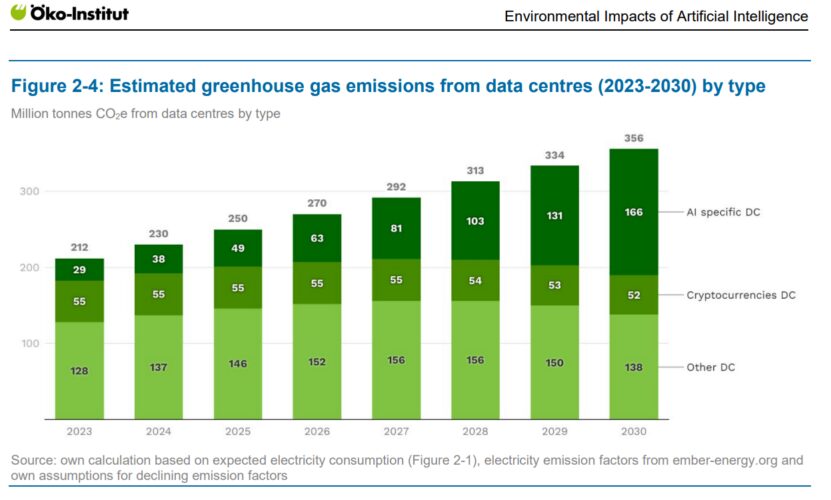

The study projects the power consumption of data centres servicing the needs of various applications of AI will be 11 times higher in 2030 than in 2023, with a subsequent increase in emissions from 29 MTCO2-e in 2023 to 166 MTCO2-e in 2030 (a calculation that factors in an increasing share of renewables).

Other environmental burdens include the water required for cooling, which will almost quadruple to 664 billion litres, and the additional electronic waste generated by the expansion of data centres and AI capacity, which will amount to up to 5 million tonnes, over the same period. In addition, 920 kilotonnes of steel and around one hundred kilotonnes of critical raw materials will be required.

While major data centre operators such as Amazon, Meta and Google have played a central role in signing power purchase agreements with many renewable energy facilities, incentivising their growth, the vast power consumption of these companies generally far exceeds deals done with clean power providers, resulting in a net addition of greenhouse gases thanks to their new demand.

The result, says Jens Gröger, Research Coordinator for Sustainable Digital Infrastructures at Oeko-Institut, is that ‘in the years ahead, data centres will continue to rely on fossil fuels such as natural gas and coal – with correspondingly high environmental costs.’ The major technology companies are also investing in nuclear power plants and small modular reactors (SMRs).

The projected climate impacts of AI-specific applications for data centres overtake cryptocurrency mining in 2026, and other data centre applications (such as file storage and streaming) in 2030, in the study’s projections:

Australia’s power grids are facing material growth in data centres in the coming years, to the extent that the grid operator is considering the issue and specifically modelling its impacts in the assumptions used in system planning.

There is also rising evidence of conflict between the companies building data centres and renewable energy interests.

A recent study published for The Technology Collaboration Programme on Energy Efficient End-Use Equipment (4E TCP) found that:

“In Australia, data centres currently use an estimated 8–12 TWh (3–5% of national electricity use) according to investment banks Morgan Stanley and UBS (Hannam, 2024; Kitchen, 2024). Both banks project a rapid increase to 2030, with UBS projecting a more than doubling to 28 TWh by 2030, while Morgan Stanley projects a range of 14– 43 TWh”

Of the approximately 230 terawatt hours of electrical energy consumed in Australia in calendar year 2023, the study estimates that 8 to 12 TWh related to data centres, around 3 to 5%.

If that number climbs significantly, it could show the same effects in Australia as it has in more data-centre heavy regions such as Ireland and the US, where fossil fuel generators facing exit find new life in the new demand.

The Greenpeace study suggests three key pathways to ensuring data centres help rather than hinder:

- – The introduction of binding transparency and accountability requirements for providers of data centres and AI services, including the collection and publication of key figures relating to data centres, the introduction of an efficiency label for data centres and key figures on their environmental footprint that are specific to AI services.

– Ensuring grid integration and adaptation to renewable energy generation volumes by covering the loads at suitable times with capacities from clean energy or with their own battery storage systems.

- – An update of the legal framework to take into account the environmental impact of artificial intelligence. This includes, for example, an impact assessment that provides for a structured and specific environmental assessment of AI systems.

It will be increasingly important for the Australian government to consider these options, and it is urgent.