A report released today has called for reform surrounding Australia’s electricity network tariffs, arguing that households pay too much for power.

The Grattan Institute has released, Fair Pricing for Power, detailing how inefficiently Australia charges its electricity, as well as recommending strategies to improve the market that will save consumers a large chunk of their quarterly bill.

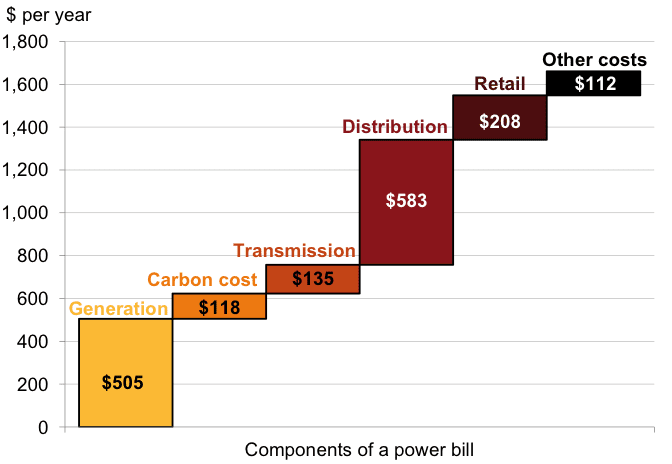

Since 2006, the average household power bill has risen 85 per cent, from $890 to $1660 a year. Network charges, such as power retailer costs, power generators and compliance costs, make up around 43 per cent of the $1660 the average Australian household pays for power each year. (See graph below).

Grattan proposes that this percentage of the bill that goes to fund the network should no longer be based on total energy use. Consumers should insteadpay for the maximum load they put on the network.

Furthermore, this method of charging customers also has implications on where a person choses to reside – with large discrepancies been seen in electricity bills state to state (see graph to right) depending on how much retailers choose to invest in their distribution networks.

Furthermore, this method of charging customers also has implications on where a person choses to reside – with large discrepancies been seen in electricity bills state to state (see graph to right) depending on how much retailers choose to invest in their distribution networks.

Despite what popular media and some politicians would have consumers believe, carbon costs account for approximately seven per cent of an average yearly electricity bill.

Historically, electricity is charged by sending a representative to read meters at the home. This meter is measured at the ‘standard’ amount of power used at the home without regard for when during the day, week or year it is consumed and is then multiplied by the unit cost of power to get the total bill.

This type of calculation is both unfair on some customers and does not reflect the cost to distribution businesses of running the network. According to the Grattan Institute, the average customer subsidising others pays around $150 too much for electricity each year.

Using a new air conditioner, as an example, added $1550 to the cost of running an electricity network to provide the additional load, whereas the household owner will only pay around $53.40 extra a year, with the remainder of the cost borne by other consumers.

Additionally, customers who consumed most of their electricity outside of peak demand times, typically late afternoon and early in the evening, may pay substantially more than their fair share or costs the report found, while others effectively received a subsidy.

If the tariff was in operation over the past five years, the Grattan Institute believed $7.8 billion of the $17.6 billion spent on new infrastructure, could have been saved.

Types of meters range from accumulation, two-rate and interval to smart meters with smart being remotely viewed in real-time and accumulation being the typical and historical meter.

The Institute recommends all Australian households install either interval meters, recording energy use ever half an hour, or smart meters that could more accurately record the homes’ maximum capacity. Currently, Victoria is the only the only state that has smart meters installed in every home, with a mandatory rollout between 2009 and 2013.

The report recommended, until all houses can be installed with smart meters, they should substitute with interval meters, meaning that consumers would be charged a rate closer, but not exact, to their maximum capacity.

Furthermore, when consumers request it, electricity retailers should be required to supply them with an interval or smart meter to enable billing based on actual maximum usage.

To make these recommendations ‘policy friendly’ the report suggests that policymakers and businesses need emphasise the fact that the proposed reforms will not increase the revenues of distribution businesses but rather, the short-term losses some customers face will go towards reducing the bills of other customers who use the network more efficiently.

Not only will this direction encourage electricity users to switch off appliances during peak periods but it will also create an incentive to use smarter, money-saving technologies such as timers that allow dishwashers to run late at night.

Australian businesses, including electricity retailers, will have an incentive to introduce new technologies – particularly batteries that can be stored and used at off-peak times – to help reduce household’s maximum capacity requirement.

Interestingly, solar has somewhat inadvertently increased the uptake of more accurate electricity reporting methods. The widespread adoption of rooftop solar has required the installation of interval meters to measure inflows and outflows of power, so that households can be paid for electricity sent from the home.

To paint a picture of meter uptake in New South Wales, Ausgrid supplies power to around 1.6 million customers; over half a million of these customers have interval meters, 3000 customers have advanced interval meters andnearly 18,000 have smart meters.

Internationally, the British Government has adopted a mandatory rollout of smart meters by 2020. This move is expected to provide £6.2 billion of net benefits to the UK over the years to 2030, costing £10.9 billion but expecting to deliver £17.1 billion in benefits