Recently, I wrote at RenewEconomy about how Australia’s government’s resources department, the Office of the Chief Economist within the Department of Industry, Sciences, Energy and Resources (DISER) has been very noticeably over-forecasting thermal coal exports over the past few years.

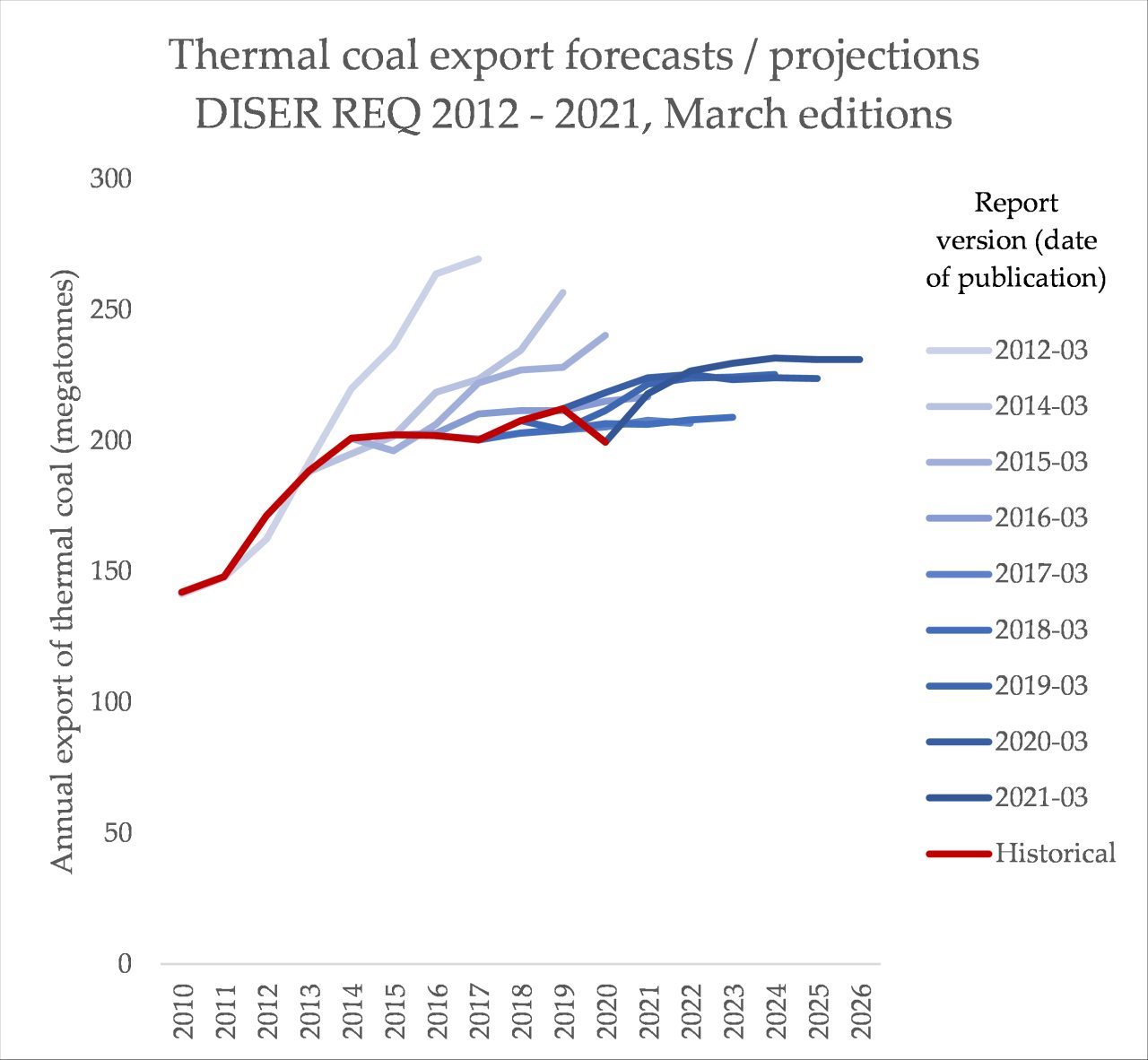

In that post, I compared the March ‘Resources and Energy Quarterly’ (REQ) report’s forecasts each year to historical data on the amount of thermal coal that Australia has exported to other countries. With a few exceptions, the reality has mostly ended up noticeably lower than the prediction:

It’s a significant problem, for Australia. Yesterday, the new Deputy Prime Minister, Barnaby Joyce, said “No one likes big holes in the ground … but the point is, you like your health system, you like your education system. This money has to come from somewhere. From the red rocks – iron ore. From the black rocks – coal”.

Putting aside the paltry amount of money that actually flows into government coffers from the fossil fuel industry relative to the profits that flow to the companies, will the cash from black rocks keep flowing? Even the government is starting to have doubts.

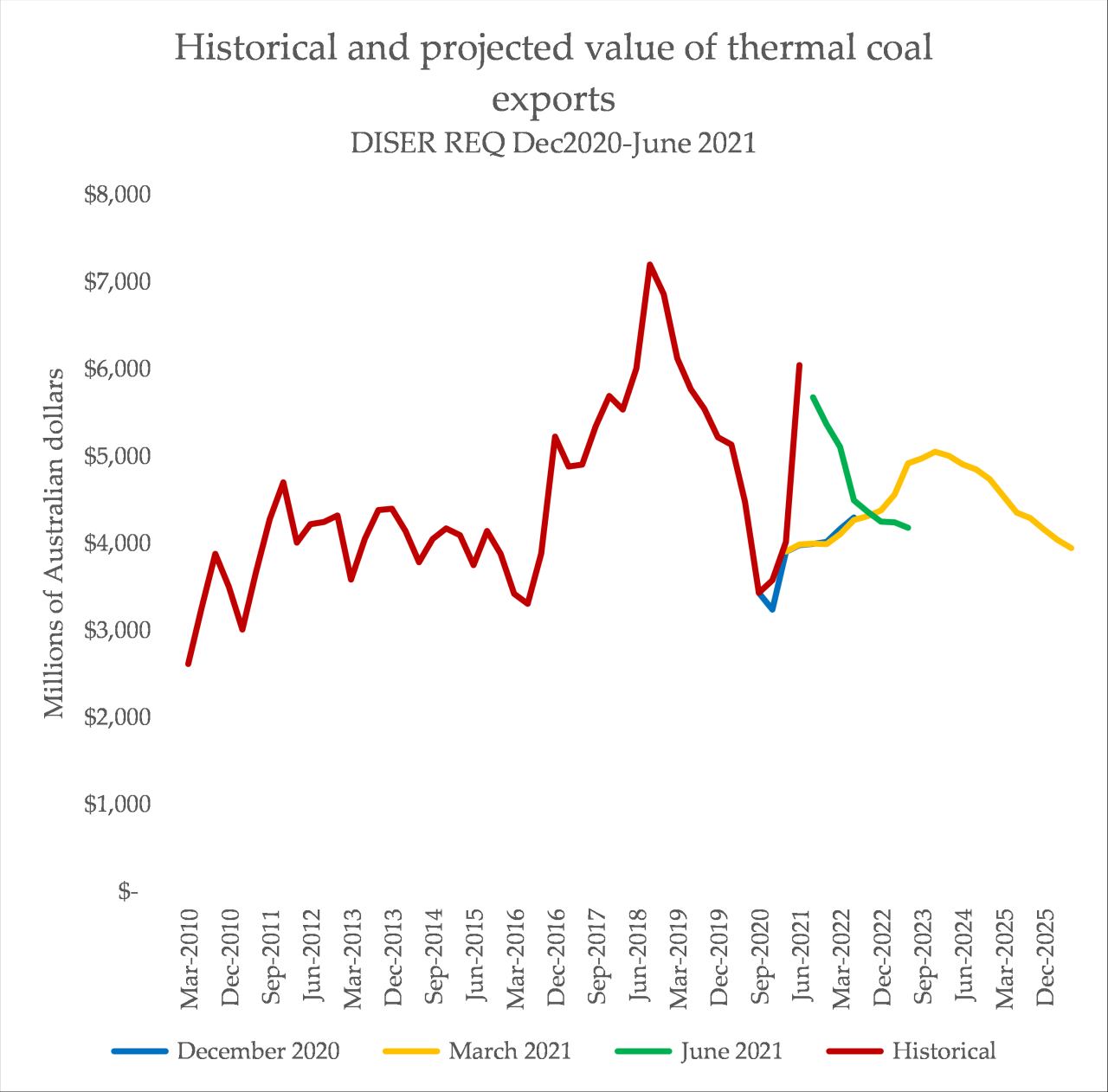

Outside of March, the Quarterly REQ only publishes a shorter-term forecast; only a few years instead of around six. The latest update, the June 2021 REQ, includes a very significant and notable adjustment to the forecast of thermal coal export volumes made in the previous report – a forecast of volume of 674 megatonnes of thermal coal exports from 2021 to 2023 has been revised downwards to 623 megatonnes over the same time period, a reduction of around 50 megatonnes.

This is quite significant, because this particular forecast has, as mentioned above, a bad habit of over-predicting coal export volumes. To demonstrate this, we can overlay the two most recent forecasts to the long history (blue shades) of thermal coal forecasts:

It’s worth noting that though thermal coal exports are flattening, the value of those exports have increased, thanks to a noticeable rise in thermal coal prices. But that price spike is expected to fade, meaning the forecast for Australia’s thermal coal export value in 2023 has fallen quite noticeably from the previous forecast:

What is going on here? Why the sudden pessimism about the future of coal exports?

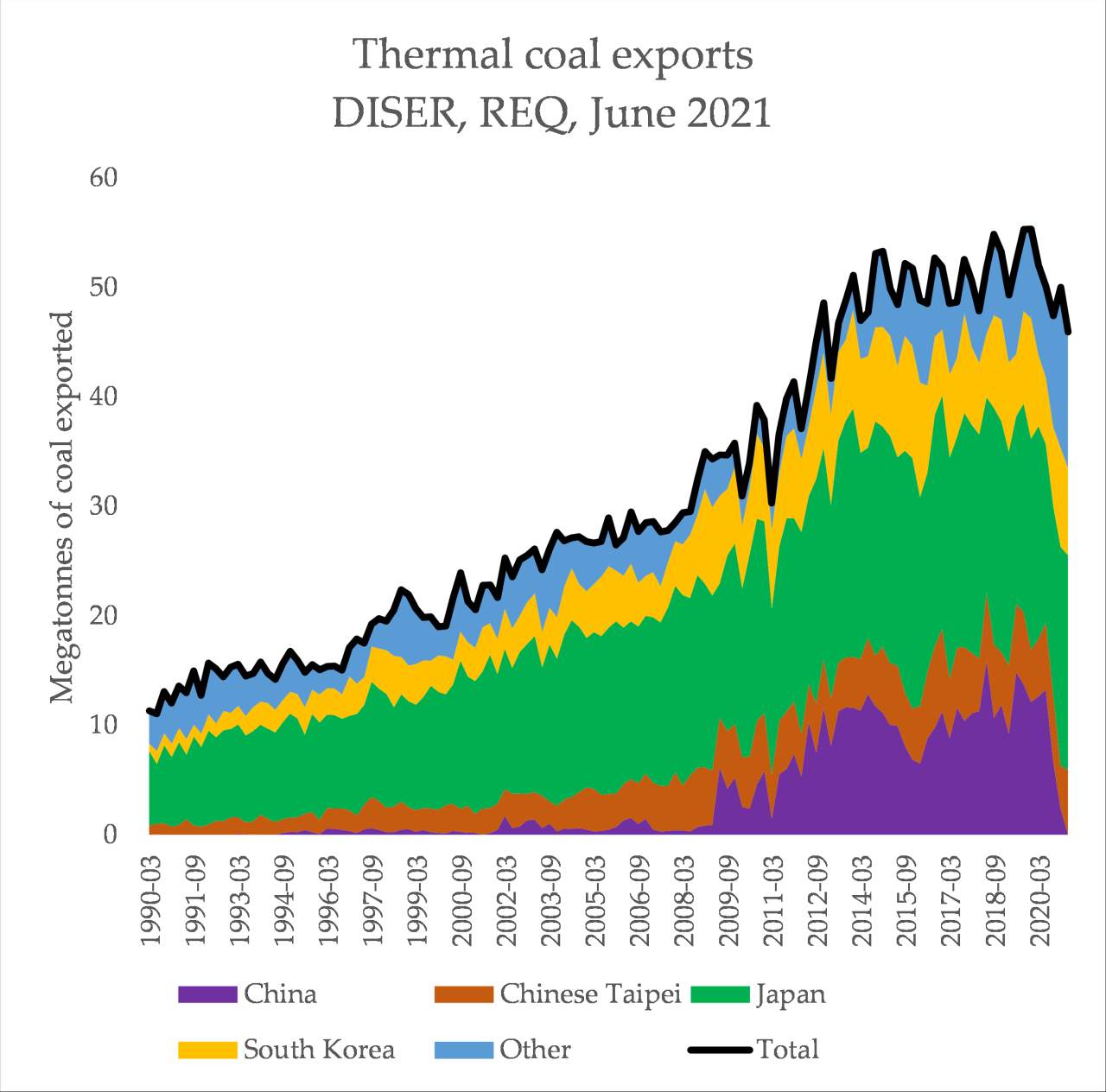

“The downgrade is largely because of a slower than previously expected increase in coal imports into India and faster falls into Japan and South Korea”, wrote Argus Media, a resources analytics company. “These countries have supported Australian exports during Beijing’s unofficial ban on Australian imports into China since October, with the weaker buying activity to drag on Australian exports over the next 2½ years”.

China’s ban on Australian thermal coal is really something to behold. Despite pleas that other customers would increase purchases to fill the gap, it’s had a noticeable impact on total thermal coal exports out of Australia:

Perhaps the realities of shrinking global demand for thermal coal are beginning to materialise. Both Japan and South Korea are seeing declines in the output of their coal-fired power stations – Japan, since 2013 and South Korea since 2018. China’s coal growth is decelerating, and will likely peak within the next five years.

Of course, Australia’s coal exports should fall. If it doesn’t, it means global climate targets are failing badly, and that the impacts of climate change, such as heatwaves and extreme bushfires, will be significantly worse, including in Australia. Every shipment of fossil fuels extracted in Australia and sent overseas is burned, and when it’s burned, damage to every country in the world is locked in.