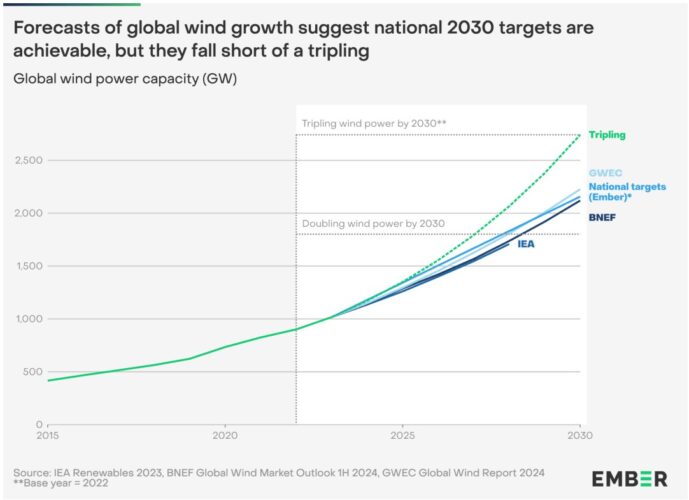

Global wind energy capacity is currently on track to more than double by the end of the decade, with national targets set to add over 2.7 terawatts (TW) by 2030, but this remains short of the tripling of capacity required by the agreement reached at last year’s COP28 climate change conference.

World leaders agreed at the UN’s COP28 climate change conference in December 2023 to an historic goal of tripling global renewables capacity by 2030 – seen by both the International Energy Agency (IEA) and International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) as the optimal pathway to keeping a 1.5°C warming within reach.

A new report published this week by independent global energy think tank Ember analysing national wind targets finds that current wind capacity targets amount to 2,742GW worth of new capacity by decade’s end.

This, while a mammoth achievement if successful requiring massive funding, still only represents a 2.4 times increase from the 901GW worth of wind energy capacity in operation at the end of 2022, leaving a gap of 585GW which would achieve the necessary tripling of wind energy capacity (2,742GW).

The report analyses 2030 national wind targets in 70 countries plus the European Union, which collectively represent 99% of current global wind capacity.

It found that the current trend towards a 2.4x increase is due almost entirely to China which is expected to “over-deliver” at the same time as “the rest of the world in aggregate is on course to under-deliver.”

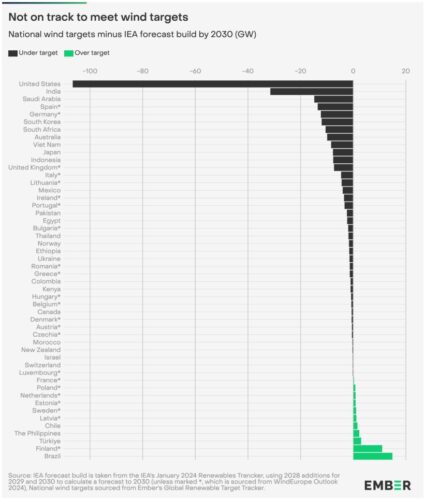

According to Ember, large wind markets such as the United States, India, and the European Union have a large gap between forecast installations and what’s needed to meet their current 2030 targets. Australia is also well under target (see table below).

“Of the 51 countries with forecast data and targets, only six are projected to meet or exceed their 2030 wind target, while 45 are expected to fall short,” said Ember. “Those gaps are biggest in large wind markets such as the US, India, and the EU.”

As can be seen below, though the second largest wind market in the world after China, the United States is also “the country with the largest GW gap between forecast installations and what is needed to meet their 2030 target.”

In fact, according to Ember, wind energy capacity additions in the United States are well behind where they need to be.

Only 6.4GW of new capacity was added in 2023, well behind the IEA’s main forecast of 16.5GW per year between 2024 and 2028, which itself is only half of the necessary 32GW needed to meet even the country’s implicit renewables target.

Similarly, India – the fourth largest wind market globally – has the second largest gap between forecast installations and what will be needed to meet a 2030 tripling of capacity. Currently, the current build rate of new wind capacity in India sits at only 2.8GW in 2023, well below the required 9.3GW needed.

Conversely, countries like Brazil and Turkey are both on track to exceed their 2030 wind energy targets.

But with wind and solar expected to provide over 90 per cent of the growth in renewables capacity for a global tripling, more is needed across the board.

“Governments are lacking ambition on wind, and especially onshore wind,” said Dr Katye Altieri, electricity analyst at Ember. “Amidst the hype of solar, wind is not getting enough attention, even though it provides cheap electricity and complements solar”

Ember’s analysis concludes that rapid growth in a few key countries and the upward revisions of forecasts in other regions indicate that, with the right combination of policy, regulatory, and financial support, rapid and large-scale growth is possible.

“Wind energy must be at the heart of the energy transition, every gigawatt installed is another step towards a confident green world,” added Ben Backwell, CEO of the Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC).

“Targets play a key role in setting out a direction of travel, but the only thing that truly fights climate change, delivers clean industry, and provides secure energy is genuine action that delivers on those targets.”