“Give us more load. And, please, switch off that rooftop solar.”

These are not instructions you hear every day, but they have been the “cri de coeur” from Australia’s Energy Market Operator this week as it battles to deal with a South Australia grid isolated by storms from the rest of the market, and one of the world’s highest penetrations of rooftop solar.

AEMO has ordered local authorities to switch off as much rooftop solar as they can, and encourage as much electricity use as possible, as it seeks to create enough “load” to give it control of a grid that fears could spin out of control if struck by another major event.

It’s quite the turnaround for the state’s solar households.

It was only a few weeks ago that SA Power Networks, which owns the local poles and wires in South Australia, was boasting of a fantastic new achievement – rooftop solar had met all local demand for more than five hours in a row in the middle of a sunny Saturday.

It was indeed, a major milestone, and a sign of things to come: This is the state with the largest share of wind and solar of any gigawatt scale grid in the world – 66 per cent of local demand in the last 12 months. And rooftop solar is a major part of that.

It is also a sign that Australia’s grid is rapidly changing from a centralised, fossil fuel based system to a renewable and increasingly distributed grid. Consumers are now producers too, and rooftop solar is chasing base-load coal and other fossil fuels out of the grid.

This week, though, SAPN had to temporarily change its tune, and has been desperately trying to cut off as much rooftop solar as it can, by sending signals over wi-fi, tripping inverters through increased voltage, and sending out public pleas for customers to switch off their rooftop solar systems, and switch on anything they can.

What has changed?

When rooftop solar reached more than 100 per cent of local demand in late October it wasn’t a problem because the grid in South Australia was connected to Victoria and could send excess power to its neighbour.

That meant there was still enough “load” in the grid, and AEMO could use a small amount of gas generation for grid security, and be comfortable in the knowledge that it had enough leg room and levers to deal with any unexpected events.

The storm that blew through South Australia last Saturday afternoon changed all of that. It tore down one transmission tower, triggered a trip in multiple circuits and “separated” the state grid from the rest of the National Electricity Market.

The state is now on its own, and large amounts of rooftop solar threaten to become more of a liability than an asset, because if rooftop solar can meet all or most of local demand, it would leave few or no levers for AEMO to pull if another major incident affects the grid.

Which is why the call went out from AEMO at the start of the week to “Give Us More Load.” It asked major energy users to turn on whatever they could during the middle of the day, and called on SAPN and the state government to switch off small solar farms.

Signals were sent to all the recently installed rooftop solar systems (about 100MW) that are fitted with new inverters that can be “orchestrated” – or switched off – by remote control. Voltage control from SAPN might have tripped inverters in another hundred or so thousand homes, removing another 300MW.

On Thursday, expected to be mild and sunny – a day when rooftop solar might well account for nearly all of domestic demand in the middle of the day in normal circumstances – the remaining households (who have older inverters that can’t be controlled remotely) were asked to switch off their solar systems.

They were also asked to switch other things on, anything – pool pumps, vacuum cleaners, electric vehicle chargers, anything that could create new load and give AEMO the head room to switch other controllable generators on.

Is all this the result of rooftop solar PV being a bad thing?

Not at all, rooftop solar and other distributed generation and storage will be a key component of a modern grid, and will also increase reliability, particularly when paired with battery storage in local communities.

But it does underline why AEMO is insisting on new inverter standards that allow it to “orchestrate” rooftop solar, turning it into a visible asset that can be controlled rather than an invisible wildcard that can derail its best laid plans. Some are calling on measures to control legacy rooftop solar systems installed years ago.

It also underlines the need for more transmission lines, such as the one that is being built now between South Australia and NSW, and will allow the state to shoot past its unofficial target of 100 per cent (net) renewables within the next few years.

And, of course, it underlines the need for more storage to help soak up excess solar, act as a “shock absorber” to any disturbances for the grid, and for new big loads such as hydrogen electrolysers that can act as big batteries, soaking up power when needed and switching off too if required.

The irony is that if this event occurred in the middle of summer, AEMO would be quite happy to have the rooftop solar injecting more supply into the grid, and might be more likely to send out instructions to consumers to reduce load rather than increase it.

That’s because – with the heat – there would be plenty of load in the grid as air conditioners are switched on, which means AEMO would have no problem finding generation assets it can control and use as levers if any unexpected events occur.

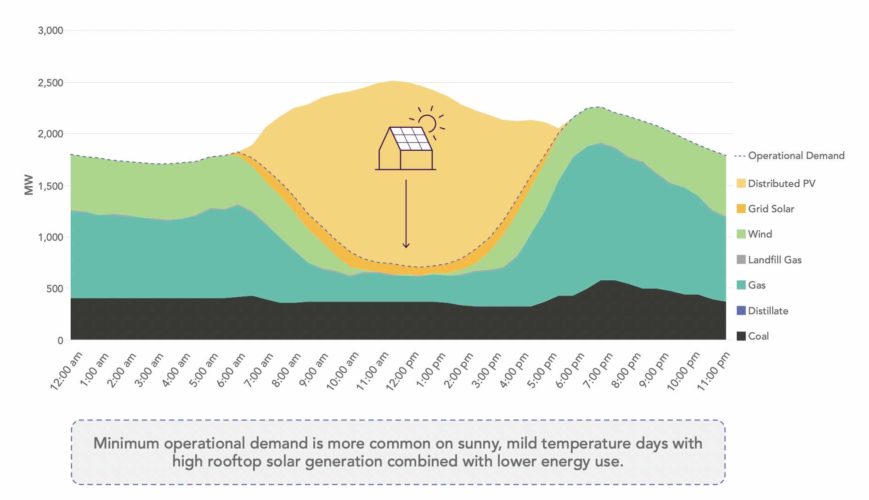

But the stunning growth of rooftop solar means that AEMO is probably less worried about peak demand events than minimum demand events, when the output of rooftop solar soaks up all or most of domestic demand.

“When rooftop solar generation is high, the need for grid-scale supply naturally becomes extremely low, which displaces grid generators,” AEMO writes in a recent explainer on the issue.

“At present, these generators provide a range of essential system services, including frequency control, system strength, voltage management, inertia, and so on.

“In periods of very low operational demand, these services need to be sourced from elsewhere or, if that isn’t possible, AEMO must intervene to keep the grid in a secure operating state.”

Over time, battery inverters are expected to supply those essential services, but the technology is still being tested and rolled out. In the meantime, AEMO is working with several states to provide more flexibility over how they manage rooftop solar.

Some of the state projects, including in South Australia and Western Australia, the technologies being deployed are relatively sophisticated. In Queensland, less so, sparking great frustration from those in the industry.

See our story: “Industry slams antiquated, brutal” solar switch-off plan in Sunshine State.”

The problem in South Australia this week is that – given the unique circumstances – not enough solar has been able to be dialled down, so AEMO has had to resort to using more brutal methods to protect grid stability and minimise the likelihood of a state-wide blackout.

Its main concern – because the state is isolated – is “trip risk” – i.e. if there is another big event that trips another transmission line, or another generator, then this could flow through to all the solar inverters it hasn’t been able to control.

Which is why it wants to have controllable assets at its disposal. Contingency plans are in place, but fingers are still crossed.

See also: Western Australia sets new renewables record of 81% – in world’s biggest isolated grid