The federal Coalition government’s gas-led transition plans have again been questioned, this time by the Australian Energy Market Operator, which says overall gas consumption is likely to fall over the next 20 years and may virtually disappear in the grid because it can’t compete with renewables or green hydrogen.

Prime minister Scott Morrison and energy minister Angus Taylor have put great store in their so-called “gas-led” transition, an idea (some would say a fantasy) driven by the gas industry and its lobbyists within the Coalition. It is the only identifiable energy policy the federal government has.

But critics say it is a plan built on a false premise. The critics say that gas is not only too polluting for the emissions reduction task, it is also too expensive to compete against rival technologies, particularly those driven by cheap wind and solar.

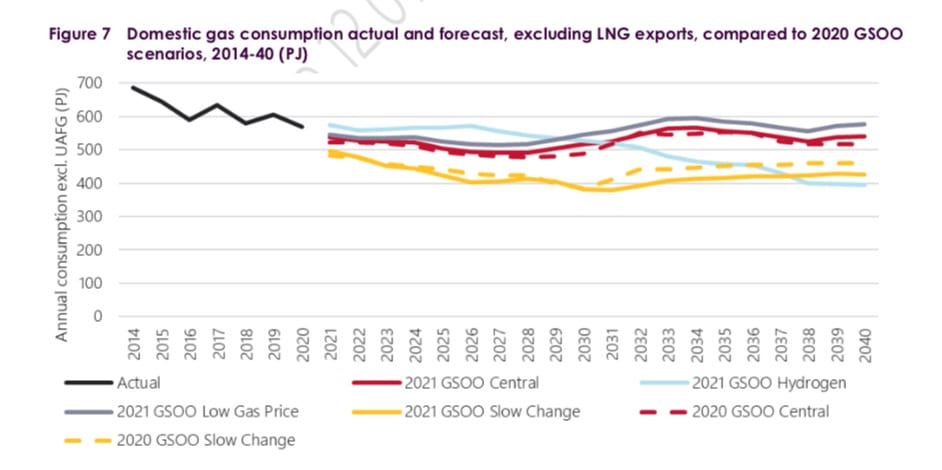

AEMO, in its annual Gas Statement of Opportunities, a detailed annual analysis of future demand based on input from the industry itself, fails to produce a single scenario where gas demand increases over the next 20 years.

Instead, the risk is heavily on the downside: from energy efficiency and fuel switching as large and small consumers choose cheaper renewable-powered electric options over gas, and the anticipated switch to hydrogen. Even a potential fall in gas prices is unlikely to boost gas demand.

“Industrial users indicate their demand is unlikely to increase, even if prices fall,” it says. “By 2040, in a future world where economic production of hydrogen is strong, gas consumption for direct use could decline by as much as 20% (based on scenario assumptions), with an even faster decline then projected to 2050.”

“Industrial users indicate their demand is unlikely to increase, even if prices fall,” it says. “By 2040, in a future world where economic production of hydrogen is strong, gas consumption for direct use could decline by as much as 20% (based on scenario assumptions), with an even faster decline then projected to 2050.”

In the electricity grid, where the federal government is trying to force at least one major gas generator into the system, the reduction in gas use is even more dramatic. Gas consumption is forecast to fall in all scenarios, even though the value of that gas will increase because of its importance in filling gaps from wind and solar production and meeting peak demand, particularly in winter.

AEMO notes that in 2020, gas generation in the country’s main grid fell 23 per cent to their lowest levels in the decade – sidelined by increasing amounts of large-scale wind and solar and rooftop solar PV.

It says this trend will accelerate – in all scenarios – in the short to medium term, as more wind and solar joins the grid, as more storage and transmission lines are built, and despite some short-term boosts from the exit of coal fired power stations.

Gas consumption in the grid is expected to fall another 40 per cent in 2021, and could be almost entirely eliminated by 2038 as green hydrogen enters the market, with the operation of the grid switching to a focus on managing demand rather than supply.

“While electrolyser loads will increase the electricity demand, the assumed flexibility of these facilities may provide a substitute for the balancing services from GPG (gas powered generation), with demand more capable of moderating to match available supply, rather than requiring GPG to operate and balance VRE variation.”

AEMO points out that gas demand – even in NSW – is expected to differ little in terms of maximum daily demand from current levels. Because of this, it emphasises that any new gas generation investment must be in fast-start equipment such as reciprocating engines, which are used sparingly.

The utility industry appears to have understood this, but the Coalition government and conservative commentators have not, still locked in the old “baseload” paradigm that has dominated theirs and the industry’s thinking for the past century. Even Labor has jumped on the gas bandwagon, because it has no confidence in its ability to carry the argument for the clean energy transition.

In the short term, AEMO says fears of gas shortages have been largely relieved by planned investments, such as new pipelines and a gas import terminal proposed in Port Kembla by billionaire Andrew Forrest.

The irony is that Australia’s gas supplies are largely dictated by its ability to meet its huge export commitments, and so the best short-term solution is to import LNG from elsewhere.

But AEMO underlines why this makes sense. It warns against too much investment in long-term infrastructure, because of the likelihood that gas demand will fall significantly.

“Australia’s energy sector is going through a rapid transition, driven by changes in consumer behaviour and efforts to decarbonise the system,” says AEMO’s head of forecasting Nicola Falcon.

“This report recognises the potential of electrification, fuel switching to hydrogen, the Australian government’s vision for a gas-fired recovery and LNG imports to all influence investment opportunities in the gas sector.

“Investments to address forecast supply gaps in the second half of this decade need to consider the transformation underway and be adaptable to manage changes in gas consumption.”