Last night, the French Parliament adopted a law to do what President Hollande proposed years ago: reduce the share of nuclear power from 75 to 50 percent by 2025 and double the share of renewables in the next 25 years. But the devil is in the detail.

Recently, my colleague Arne Jungjohann and I reviewed the overlapping between Germany and France’s energy transitions based on a study by the Friedrich Ebert Foundation. In preparation for the upcoming climate talks in Paris, the French government has now made these plans the law of the land. Here’s what you need to know about the law:

- Energy consumption will be cut in half by 2050. Fossil fuel consumption is to be reduced by 30 percent relative to 2012 by 2030. This consumption is measured in terms of primary energy, which makes these seemingly ambitious targets easily attainable – a simple matter of definition.

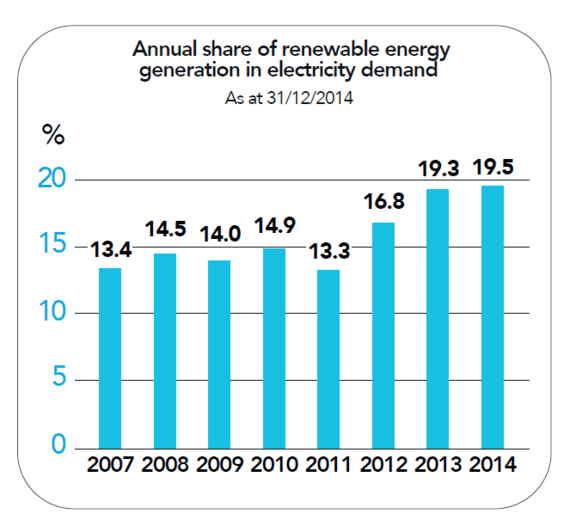

- The law makes no sense in one respect. By 2025, the share of nuclear is to drop by 25 percentage points. Yet, the share of fossil fuel is to drop. The only thing left is renewables, which made up nearly 20 percent of power supply in 2014. If renewables are to make up for the reduction in nuclear, they would have to increase to 45 percent of supply by 2025 – yet, the target for renewable electricity is 40 percent by 2030.

- France is not ramping up renewables fast enough, so it will not reach that target anyway. Furthermore, it will not reach its target for the reduction in nuclear power, which is completely unrealistic – the country would have to shut down a third of its reactors over the next 10 years.

In reality, the nuclear sector is hoping that overall power consumption will skyrocket, thereby leaving the country’s nuclear fleet untouched. The law specifies that the current fleet’s output is the maximum for the country, for instance. In other words, if the EPR reactor in Flamanville is ever completed, roughly the same capacity would need to be shut down. Turn this around, and you can see the wishful thinking: old reactors will not have to be shut down unless they are replaced with new ones.

In the end, everything about this law is unlikely, including the hope that power consumption will increase by 50 percent in order to save the existing nuclear fleet. Power demand has risen in France over the past few decades (whereas it has remained more stable in Germany, for instance), so the expectation has historic justification. It may also be over, as the charts below show. Overall, it simply too early to tell whether this new French law marks a real change in direction or simply some window dressing for the upcoming climate conference that France will host.

Source: Renewables International. Reproduced with permission.