Sunshine Hydro, a company proposing to combine pumped hydro with green hydrogen production, says it has has sold a 20 per cent option in its landmark flagship Queensland project to a First Nations group.

Sunshine Hydro says it hopes that the deal with the First Nations Greentime Energy Group (FNGEG) can be supported by financiers such as NAIF and CEFC.

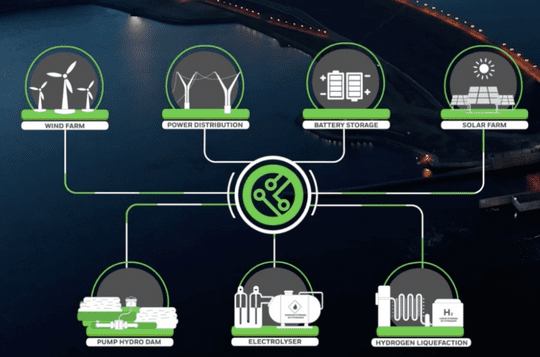

The Djandori Gung-i (Spirit in the Water) Superhybrid clean energy project at Miriam Vale, also known as the Flavian Superhybrid project is a unique proposal to deliver up to 600MW of pumped hydro capacity and up to 300 MW of hydrogen electrolysers.

Sunshine Hydro chairman Michael Mye says he expects FNGEG will become a long term partner in the project and that it will bring a team of experienced tunnellers who are currently working on Genex’s 250 MW Kidston project and the power station fit-out.

He hopes it can create a model for other renewables companies in Australia.

“We’re trying to create a platform whereby this model could be seen to be one that could work for proponents and for First Nation stakeholders around the country,” Myers told RenewEconomy.

“It’s about creating a model. These are intergenerational assets and their [FNGEG’s] motive was we want to create intergenerational assets and wealth, and this is the way we’ve gone about it.”

Myer says his company’s prospective backers, one from European and one from Asia which have experience in pumped hydro, were very supportive of the move.

FNGEG director Tony Martens says securing an equity stake is a first for them and they’re looking to roll out the model.

‘We see ourselves as a key advocate, consultant, and broker to assist other First Nations groups wanting to enter into arrangements with project proponents who are proposing clean energy projects on their country,” he told RenewEconomy.

“I suspect there will be other traditional owner groups in Queensland that start approaching us, to say how did you do and how can you help us achieve similar outcomes.”

Sunshine Hydro and its shareholder Energy Estate unveiled the “world first” super-hybrid green hydrogen project in 2022. It was valued at up to $5.5 billion and will combine as much as 1.8GW of new wind generation and 600MW of pumped hydro with 18 hours of storage.

The project components could include 300MW of hydrogen electrolysers, 50MW of liquefaction, and a 50MW hydrogen fuel cell, and would have the capacity to produce 65 tonnes of green hydrogen a day.

Commissioning is expected in 2029.

Business partners first

The Sunshine Hydro-FNGEG model replicates that already pioneered in Canada and moves beyond the royalties, jobs and training opportunities that is the business-as-usual option in Australia for resources companies.

Martens says jobs in the mining sector haven’t created intergenerational wealth — you can’t pass a job on to your children — and royalties haven’t created long-term sustainable wealth.

“I think First Nations people across the country are now becoming better informed around wanting to participate in the broader Australian economy more effectively and are wanting to engage in sustainable wealth creation opportunities,” he says.

“They’re seeing what is happening overseas in countries like Canada, where it’s mandatory for First Nations peoples to have equity stakes in energy and mining projects. Indigenous Australians are becoming more informed of those types of arrangements.”

The shift towards seeing First Nations groups as business partners, as opposed to interest groups, is appearing more in the renewable energy space.

Yindjibarndi Energy Corporation signed a green power deal with Rio Tinto in October to explore energy sales from solar, wind and battery projects on Yindjibarndi country in the Pilbara region of Western Australia to the miner.

Rio Tinto needs about 600-700MW of renewable power to displace most of its gas use from four gas-fired power stations in the Pilbara. The initial focus for the green power agreement is for a 75-150MW solar farm.

The First Nations Clean Energy Network is advocating for ownership, enabled by new financial structures, of First Nations groups in Australia’s renewable energy industry.

And renewable energy developer Octopus Australia struck a revenue sharing deal with the Larrakia Nation and the Jawoyn Association in the Northern Territory, which led to the creation of Desert Springs Octopus, a majority Indigenous owned company backed by Octopus Australia, and with a $1 billion near term pipeline of projects.

When asked why business partnerships like Sunshine Hydro’s haven’t been tried in the past, Myer says there is — following the failed Voice referendum on Indigenous recognition in the Constitution — a lot of enthusiasm for First Nations groups taking ownership stakes, but a disconnect on how to get there.

“In this case we were approached by people who have successfully built a business over time. The thing about Tony and Ash [Martens] is they’ll go into banks and people like NAIF and they still get given a short shift. It’s almost like they have to get some endorsement from white fellas first. And from the white fellas’ side it’s like, who do we talk to. I’ve always taken the view, you sit down and talk,” Myer says.

“We sat around and talked for hours about shared vision. You’ve got to do it socially. You’ve got to do it where you build trust. And the most important thing is you’ve got to do what you say you’re going to do.”

Expanding on East Coast

Sunshine Hydro is midway through a $500,000 crowdfunding exercise, which Myer says was to create an opportunity for unsophisticated investors who were keen to buy in to the company.

“We wanted to get some extra working capital as we move forward with the projects. Secondly we’re a B2B business and there are a lot of people saying we want to invest in something that can make a difference at scale. There are not a lot of opportunities to do that,” he says.

“We picked up a lot of like minded, some sophisticated investors and unsophisticated investors and gave them an opportunity to get in.”

The Djandori Gung-i is the company’s flagship project, but it is also planning a 300 MW pumped hydro project in northern NSW near the state interconnector, and they are negotiating over land near Gladstone for a 600-800 MW project dubbed Juliette which is co-located with a wind farm.

“We can contract wind and solar long, and can sell carbon-free energy long, but when we contract wind there is no curtailment risk for them and we can share transmission costs etcetera,” Myer says.