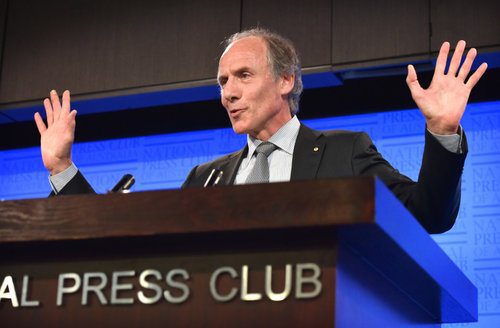

Australia’s chief scientist Dr Alan Finkel has used a speech to the National Press Club to argue – again – that Australia should use its coal and gas resources in the production of hydrogen, saying that it would provide an easier pathway to establish a hydrogen industry.

In the speech to the National Press Club, Finkel made a case for kick-starting Australia’s hydrogen industry by focusing on production from fossil fuels combined with carbon capture and storage technologies, rather than focusing on wind and solar.

Finkel said it was important that Australia did not cut itself off from the resources altogether, and that such a pathway could help avoid potential constraints on other resources if Australia was to instead focus on hydrogen produced using wind and solar.

Finkel served as the architect of the National Hydrogen Strategy released last year that appeared designed navigating the fine line between promoting the role hydrogen could play in decarbonising Australia’s energy system and delivering a proposal that federal energy minister Angus Taylor and now former resources minister Matt Canavan could live with.

Hydrogen has been touted as a potential solution to many of the challenges faced by a transitioning energy system, given its potential to be produced using electricity produced from wind and solar, the ability of the gas to be stored and transported and role for hydrogen to play a crucial balancing role to variable renewable energy sources.

Several major European industrial companies are exploring how hydrogen can be used to replace coal in the steel production process and substantially reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the manufacturing sector.

Australia also has an abundance of high quality wind and solar resources, providing an opportunity for Australia to reorientate itself from being the leading global supplier of fossil fuels, to becoming the leading supplier of zero-emissions energy exports through green hydrogen production.

The likes of Professor Ross Garnaut has promoted the use of renewable hydrogen, as has the South Australia government, and ARENA boss Darren Miller suggests Australia could produce 8 times its electricity needs through wind and solar to satisfy the hydrogen potential.

However, citing the currently higher costs of producing hydrogen through electrolysis, Finkel has advocated for using hydrogen produced from gas and coal as a way to get an early start on a establishing a hydrogen sector.

“We can use coal and natural gas to split the water, and capture and permanently bury the carbon dioxide emitted along the way,” Finkel told the National Press Club.

“I know some may be sceptical, because carbon capture and permanent storage has not been commercially viable in the electricity generation industry. But, the process for hydrogen production is significantly more cost-effective for two crucial reasons.”

“First, since carbon dioxide is left behind as a residual part of the hydrogen production process, there is no additional step, and little added cost, for its extraction. And second, because the process operates at much higher pressure, the extraction of the carbon dioxide is more energy efficient and it is easier to store.”

Hydrogen can generally be produced in two ways; using electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen, a process that can easily be adapted to use wind and solar power, or by splitting hydrocarbons sourced from coal, gas or oil, leaving hydrogen and carbon dioxide.

Recently published research commissioned by the global Hydrogen Council, and prepared by McKinsey, found that the cost of hydrogen produced using wind and solar could halve by 2030, allowing renewable hydrogen to be produced at a lower cost than hydrogen produced using unabated fossil fuels.

The findings led McKinsey to predict that by 2030 as much as 15 per cent of the world’s energy consumption could be served at lowest cost by renewable hydrogen.

In his speech, Finkel argued that the processes used to produce hydrogen from fossil fuel sources lend themselves to being integrated with carbon capture and storage, and that the most important focus was outcomes.

“I have always maintained that the focus needs to be on outcomes. The outcome in this case is reduced atmospheric emissions. We should use whatever underlying technologies achieve the goal,” Finkel said.

Finkel went on to claim that producing hydrogen using wind and solar election would place additional pressures on Australia’s electricity networks, as well as demands on Australian resources used in the production of renewable energy technologies.

“Returning to the electrolysis production route, we must also recognise that if hydrogen is produced exclusively from solar and wind electricity, we will exacerbate the load on the renewable lanes of our energy highway,” Finkel said.

“Think for a moment of the vast amounts of steel, aluminium and concrete needed to support, build and service solar and wind structures and the copper and rare earth metals needed for the wires and motors. And the lithium, nickel, cobalt, manganese and other battery materials needed to stabilise the system.”

“What if there was a resources shortage? It would be prudent, therefore, to safeguard against any potential resource limitations with another energy source,” Finkel added.

At the core of Finkel’s argument is that it would be beneficial for Australia to continue exploiting its coal and gas resources, provided it is paired with sufficient carbon capture and storage facilities, as it would maintain access to two additional energy sources and that this would be good for energy security.

It is an argument that was first flagged by Finkel at last year’s Clean Energy Summit.

The National Hydrogen Strategy was delivered to, and subsequently adopted by, Australia’s energy ministers at a meeting of the COAG Energy Council late last year.

Efforts to prevent a scenario where Australia built a hydrogen industry, as led by ACT Greens minister Shane Rattenbury, were immediately blocked by federal energy minister Angus Taylor. The COAG energy council however did agree to establish a regime for ‘labelling’ hydrogen produced in Australia with its source of origin and emissions intensity.