Planning approval for one of Australia’s most hotly contested wind projects has been delayed yet again, this time as the developer fights for the right to install more turbines, arguing that the project is not viable without them.

The Hills of Gold wind project, near Nundle in the New England region of New South Wales, has been the centre of a bitter dispute between supporters and opponents that has dragged on for years.

It appears to have divided the community down the middle, sparking a “Not in Nundle” campaign that has been adopted and imitated around the country, and featured in a recent ABC 4 Corners investigation into wind planning issues.

Hills of Gold finally won approval from the state government planning department late last year, but the approval was for only 47 turbines, and a shrunken capacity of 290 MW, down from 64 turbines in its final application and the 97 turbines originally contemplated.

The project owner, the French energy giant Engie, welcomed that decision when it was handed down last year, but argued that the turbines removed by the planning department ruling were the most productive and the project would not be viable without them.

It has asked the Independent Planning Commission – to whom the project was referred because of the high number of objections – to approve 62 turbines in all. The IPC has called for new submissions in light of the proposal.

The Hills of Gold planning approval has been closely watched by the industry, both because of its threatened derailment by the use of so-called “phantom dwellings” by its opponents, and also because planning approvals for wind projects, particularly in NSW, have been the subject of heavy delays, with only a few approved in recent years.

Engie had said that the removal of the turbine situated near the “phantom dwelling” – produced via a relatively easy to obtain Complying Development Certificate (CDC) – would set a “dangerous precedent” for other proposed wind farm developments in NSW. There are more than 22,000 MW of wind projects in the pipeline.

It appears that the department has given its approval and recommended that the company propose to buy that piece of land. The IPC is seeking more submissions on the updated proposal and has extended the deadline to July 15.

One of the most surprising and revelatory aspects of the new application is the assumed levelised cost of energy (LCOE) for the Hills of Gold project, which is revealed in a detailed report completed last month by an independent panel commissioned by the state’s planning department.

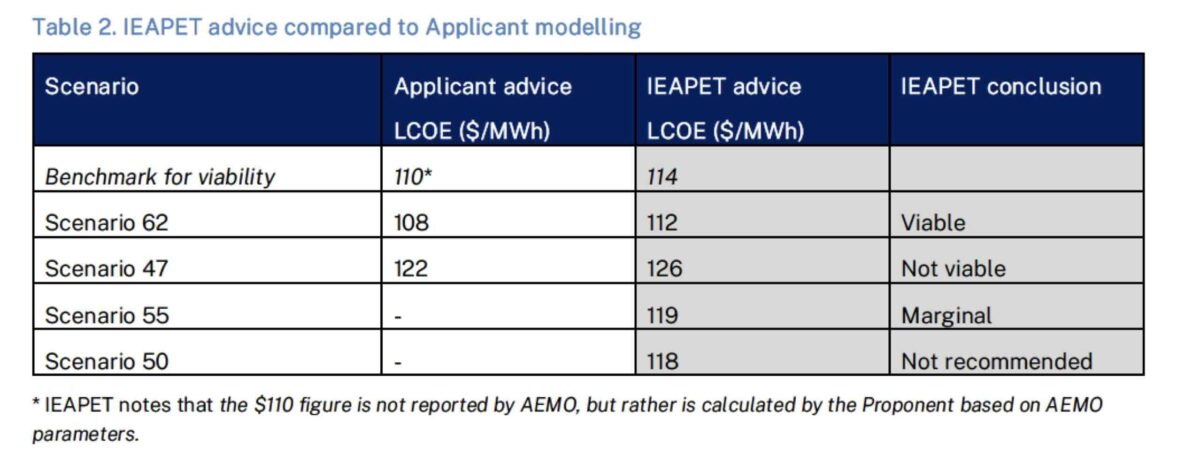

This report was commissioned because Engie argued that the LCOE for the Hills of Gold project under the approved 47 turbine scenario would be $122 a megawatt hour (MWh), which meant it would not be viable.

It said it could make money if it had 62 turbines because the LCOE would then be reduced to $108/MWh. That’s because fixed costs could be shared by more turbines, and because it could now include some of the most productive turbines, with higher capacity factors.

The independent experts panel has accepted Engie’s arguments, although it has come up with its own assessments, which vary slightly (see table above). It puts the “benchmark” price for viability at $114/MWh, and agrees that the 62-turbine layout comes under that number, but the others do not.

“Engie has advised that if this reduction (to 47 turbines) is adopted, the project would be non-viable and has provided an economic assessment in support of its advice,” the report says. “It has, however, accepted a reduction of two turbines (from the original 64) based on their environmental impacts.”

The panel said the “going rate” for power purchase agreements for wind farms in NSW is around $85-90/MWh, but revenue and profits could be increased by optimising the costs of production, and tapping into higher wholesale prices if they emerge.

These calculations are interesting because they are rarely revealed in public, given that the PPA agreements – including government ones – are hidden from view, unlike the contracts written by the ACT government to reach its goal of net 100 per cent renewables.

For the market nerds out there, the method of calculation for the LCOE may be of interest. According to the panel the LCOEs are based on inputs and assumptions from the Australian Energy Market Operator’s Draft 2024 Integrated System Plan (ISP) and it comes at the top end of the recent CSIRO GenCost report.

The benchmark figure of $110/MWh provided by Engie is calculated using those parameters – and is the level from which a generic wind farm is deemed to achieve a level of return on “which it can be assumed that a market participant would reasonably execute the project.”

Some of those parameters include a build cost for a generic NSW wind farm of $2,564/kW, a capacity factor of 32 per cent and a marginal loss factor of 0.89 (which means just over 10 per cent of output is lost as a result of congestion and grid constraints, a significant number that needs to be addressed by networks and the grid operator.

The Panel acknowledges that the $114 benchmark it settled is an approximate figure, and concedes that the ‘true’ benchmark is likely to be lower than that.

It does actually an average LCOE estimate for wind in NSW at $97/LCOE, based strictly on the ISP inputs and assumptions. Analysts suggest that the LCOE for wind will be significantly lower in larger projects, which may explain why so many proposed new projects are looking at sizes of one gigawatt or more to get the economies of scale.

“This judgement has been important in the Panel’s findings on viability because if a benchmark well above

$114 was plausible there would be greater scope for the removal of turbines not to threaten the viability of the Hills of Gold wind farm,” the panel notes.

In a later statement, Engie said it is considering the option of buying the land of the wind farm opponent which incudes the CDC. The landholder can trigger the request any time in the next five years.

“Engie has always been clear that this project would not be commercially viable at the reduced size of 47 turbines, which was originally recommended by the NSW Planning Department,” head of development Scott De Keizer said in a statement.

“We are pleased that they have taken this feedback on board – backed up by the findings of theirIndependent Expert Advisory Panel on Energy Transition – and recommended that 15 turbines be reinstated.

“This would bring the total number of turbines in the project up to 62 and allow us to proceed as planned.”