A new report from Australian and international researchers suggests there is no prospect for a new coal generator in Australia, and even existing coal generators are going to be challenged by the falling costs of renewables and storage.

The report, “Implementing coal transitions: insights from case studies of major coal-consuming economies” has been produced by an international consortium, including French think tank IDDRI, and researchers from the Australian National University, among others.

It is the Australian conclusions that are the most striking, particularly in relation to the renewed political dialogue around the need to protect existing and encourage new investments in what the Coalition government is describing as “fair dinkum” “reliable”, “24-hour baseload” power. i.e. coal.

Frank Jotzo, from the ANU, has some sobering news. The point where new wind and solar, backed by energy storage become cheaper than operating old coal plants is not far away – a conclusion more or less confirmed by AGL, with its plans for Liddell.

“Cost reductions for renewable power have been tremendous and are continuing apace,” Jotzo says.

“In Australia, there will come a point where it is cheaper to build new solar parks and wind farms firmed up by energy storage than to keep operating old coal plants.

“That is even before taking into account the plant’s contribution to carbon emissions and local air pollution,” he added.

“We used to think that point would be decades away, now it may be coming quite soon. The transition could be fast and will bring many benefits. But we need to be prepared, and right now we are not.”

Jotzo draws his conclusions from recent price discoveries in contracts for new wind and solar farms, the falling costs of batteries storage, and the initiatives and declarations of the likes of UK billionaire Sanjeev Gupta, who clearly believes his own assessment because he is inviting billions of dollars in solar and storage.

Jotzo says it is clear to him that a cross-over point is fast approaching, where the combination of renewables, storage, demand response and portfolio diversity will beat the operating costs of existing coal-fired power stations.

“At that point, it will make commercial sense to replace coal plants with new renewables installations irrespective of their remaining technical lifetime, and even before taking into account carbon emissions and local air pollution,” he said.

“When this point will be reached is uncertain and depends on regional circumstances, however recent indications are that the crossover may occur much sooner than was thought previously.”

Jotzo says the economic factors are accelerated by the changes in the grid that are required of increased penetration of variable sources such as wind and solar.

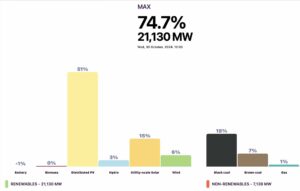

That requires more flexibility, and less production from baseload plants. Little wonder their owners – such as Trevor St Baker of Vales Point – are pushing to limit the amount of wind and solar produced at any one time to 50 per cent of local generation.

Jotzo has developed several different scenarios about the closure of coal generation in Australia, based on the assumption that coal plants rarely last until 50 years – which is the basis of most forecasts in mainstream Australia. The average age of the last 10 coal plants to close was, in fact, 40 years.

This is reflected in the top graph of the panel below, the top showing the assumed 50-year lifespan, followed by an assumption of closures after 40 years.

But then Jotzo suggests that the exit of the coal fleet may be dramatically accelerated by the declining economics, particularly as more renewables are added to the system.

In one, Jotzo assumed that the remaining coal plant retirements start at age 55 years in 2017 and falls gradually to 30 years by 2050.

This scenario sees one major retirement (Liddell, approximately in line with the owner’s announcement of intended closure) in the first half of the 2020s, and a rapid reduction in the second half of the 2020s, to less than half the existing capacity by 2030.

“All but one of the remaining plants would retire during the 2030s,” he says.

In the second scenario, the retirement age starts at 50 years in 2017 and falls to 30 years by 2037, prompting a situation where the deterioration of the economics of coal plants plays out more rapidly.

“Coal plant capacity is then reduced to less than one-third of the present level before 2030, and by 2035 only one plant remains,” Jotzo concludes.

And then he warns:

“Even more rapid closure scenarios are plausible if the cost of renewables including incremental cost for firming intermittent sources falls to levels that are consistently below the cost of operating coal power plants, including relatively young plants that are far from the end of their technical lifetimes.

“Such scenarios do not seem far fetched, however we do not present them here, instead opting for relatively conservative assumptions.”

And the news is not much better for the owners and operators of Australian’s thermal coal mines, and as yet undeveloped projects.

Oliver Sartor, the coordinator for Coal Transitions at IDDRI, a French think tank that co-leads the international project, said even major coal-consuming countries are now seriously exploring their options for a shift away from coal in the coming decade or two.

“Importantly for Australia, this includes some of its major export customers, like China and India. It also includes relatively poor developing countries with lots of coal like South Africa, who are now moving to the view that renewables could be a cheaper way to power economic development.

“Our analysis concludes that the most likely scenario now is that global thermal coal demand will have peaked and be declining by the early to mid-2020s.

“Importantly, this is true even if the 2°C goal of Paris agreement is not fully implemented.

“Climate is just one of several factors that are at play, such as the economic rebalancing of the Chinese economy, the growing political importance of air and soil quality and water availability in developing countries, and the fact that in places like India or Africa it’s often cheaper to provide access to electricity through renewable mini-grids than big expensive coal plant.”