The owners of Australia’s ageing and increasingly decrepit coal generators have known for some time what a duck curve looks like. They may never have imagined, however, that it would grow this steep, this quickly.

AGL admitted this year that it had been caught by surprise by the growth of rooftop solar and renewables in general, as it implemented its mad scramble to split its business between the dying legacy coal assets and something worth saving in a clean energy future.

Clearly, they weren’t paying attention. Solar had been well announced as a threat to the future of coal generation nearly a decade earlier, by their peers in Queensland who were getting their first taste of the solar duck curve. Now it’s about as steep as they can manage.

The latest Quarterly Energy Dynamics report from the Australian Energy Market Operator highlights, once again, the increasingly rapid change in the country’s main grid, where renewable output is at record highs – both in 30-minute and monthly intervals, and coal is being slowly chased out of the system.

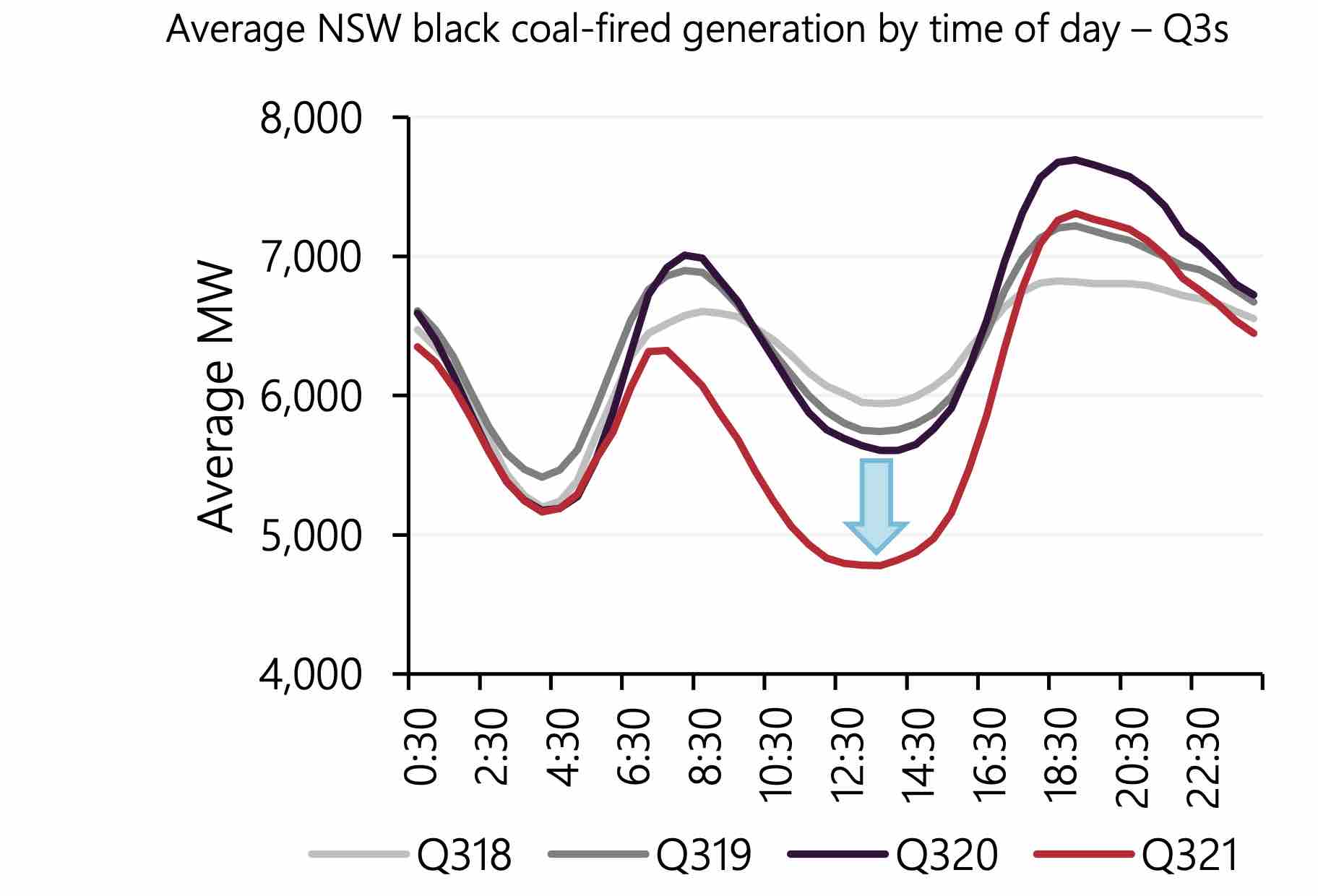

The duck curve – created by the hollowing out of daytime demand by rooftop solar – is steepening. In the graph at the top it shows the red curve from the latest quarter taking out another gigawatt of average coal demand in NSW.

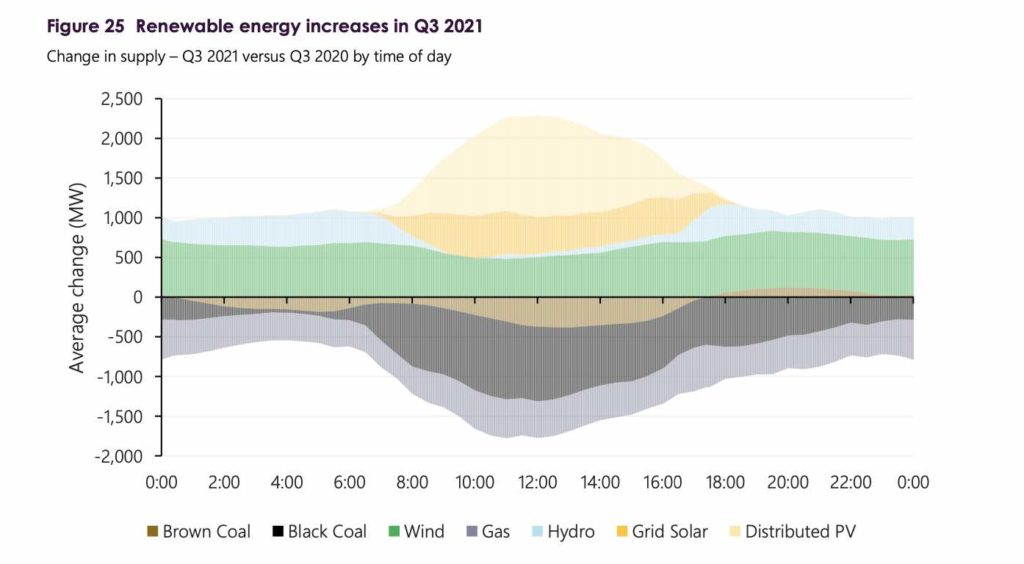

This next graph highlights what the broader change in the grid looks like, with wind, solar and hydro all increasing from a year earlier, and coal and gas both falling, particularly during the day thanks to rooftop installations but also at night thanks to increased wind and hydro.

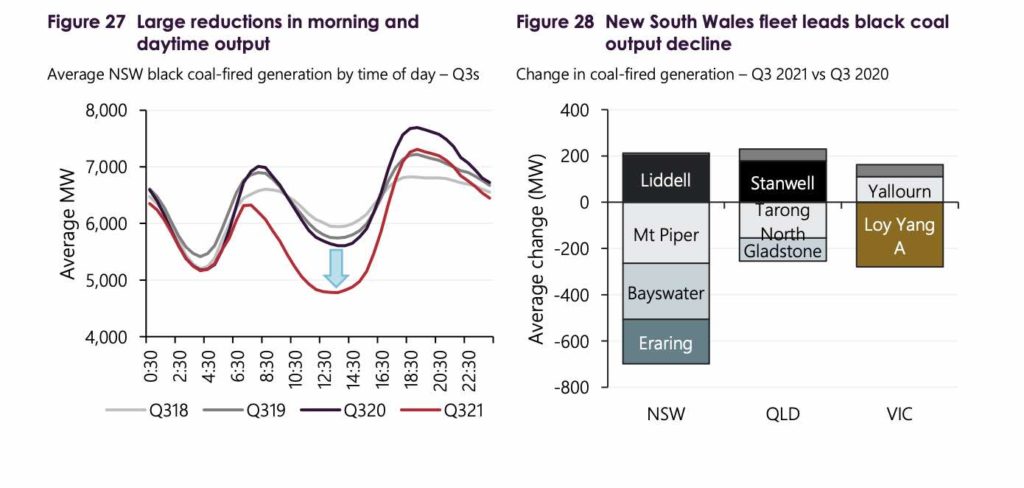

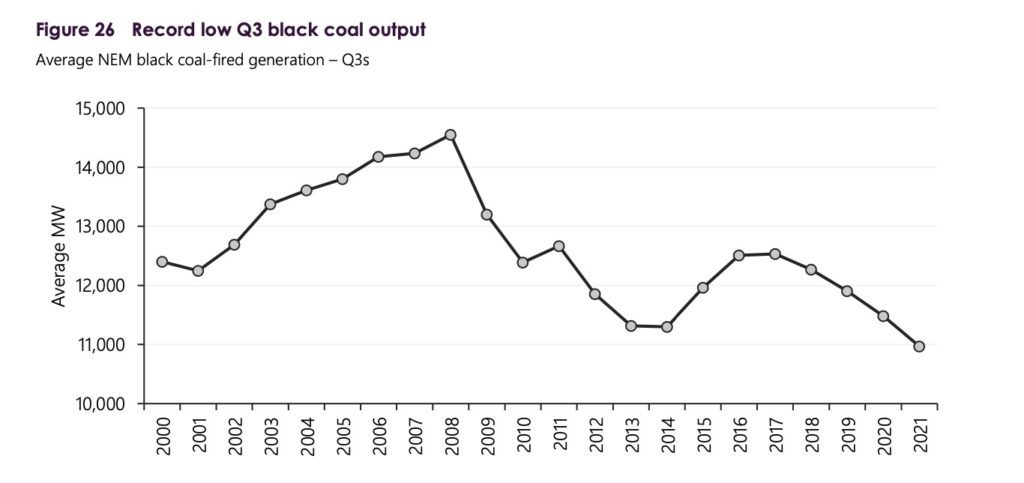

The QED reports that average black coal generation in Q3 (July to September) fell to 10,969MW – its lowest Q3 output since the National Electricity Market was created more than two decades ago. NSW coal plants were worst hit, down by an average 486MW, with Queensland generators down by 25MW.

It was the NSW coal fired power stations that suffered most, as this graph above illustrates. Mt Piper, Bayswater and Eraring had big reductions. Only the soon to be closed Liddell reported an increase, but that’s compared to previous outages last year.

And since the end of Q3, the situation has got worse for the coal generators. Australian operating grid demand (after the big bite from rooftop solar) has hit a record low of below 13,000MW, and AEMO predicts it could fall to 4GW to 5GW by 2025.

That doesn’t leave much room for baseload coal. As the big coal generator owners admit, baseload is dead as a business case, and the coal generators don’t like dancing or ramping.

Little wonder NSW energy minister Matt Kean is getting his own ducks lined up in a row so he has enough renewable and storage capacity to replace them if, as he suspects, all the coal generators in NSW are out the door by 2030.

This next graph shows how the game has changed. Just over a decade ago, the big worry was how to meet peak demand, it forced a scramble of network upgrades that added hugely to bills. But now, it’s how to manage minimum demand, and the focus is now on storage, or creating new load or shifting old load.

The NSW coal generators suffered most during the daytime hours, where average output fall by an average of 887MW over the previous year, with unplanned outages also a factor. Queensland fared better because there was more load demand from busy LNG plants and mining activity.

The NSW coal generators tried to survive by shifting more bids to price bands above $40/MWh this quarter, partly to deal with record high international coal prices, and partly – in the case of reasonably flexible generators like Eraring – to dodge low spot prices.

(If they bid their price high, less likely to be dispatched. If a coal generator does not want to be switched off, it will bid its price low, usually deeply negative during the daytime to ensure it is dispatched).

Brown coal generators, which like to trundle through the day without interruption, also suffered an average 125MW fall in output as they were displaced by lower priced sources such as wind and solar, and utilisation rates decreased from 99% in Q3 2020 to 94% this quarter.

The good news is that after dealing with the explosion at Callide, wholesale prices resumed their downward trajectory, and emissions fell to a record low of 31 million tonnes, and an average emissions intensity of just above 0.6 tonnes of Co2 equivalent per MWh.