Over the past week the Russian military has taken control of the Chernobyl nuclear site in Ukraine and there have been two near-misses with military attacks threatening radioactive waste sites.

But the greatest nuclear hazards lie ahead and concern Ukraine’s operating nuclear power reactors. International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Director General Rafael Mariano Grossi said on March 2:

“The situation in Ukraine is unprecedented and I continue to be gravely concerned. It is the first time a military conflict is happening amidst the facilities of a large, established nuclear power program.

“I have called for restraint from all measures or actions that could jeopardise the security of nuclear and other radioactive material, and the safe operation of any nuclear facilities in Ukraine, because any such incident could have severe consequences, aggravating human suffering and causing environmental harm.”

Grossi cited a 2009 decision by the IAEA General Conference that affirmed that “any armed attack on and threat against nuclear facilities devoted to peaceful purposes constitutes a violation of the principles of the United Nations Charter, international law and the Statute of the Agency.”

Worst-case scenario

It’s worthwhile comparing a worst-case scenario with the current situation in Ukraine. A worst-case scenario would involve war between two (or more) even-matched nations with a heavy reliance on nuclear power. War would drag on for years between evenly-matched nations. The heavy reliance on nuclear power would make it difficult or impossible to shut down power reactors.

Sooner or later, a deliberate or accidental military strike would likely hit a reactor – or the reactor’s essential power and cooling water supply would be disrupted. Any ‘gentleman’s agreement’ not to strike nuclear power plants would be voided and multiple Chernobyl- or Fukushima-scale disasters could unfold concurrently – in addition to all the non-nuclear horrors of war.

In the current conflict, the nations are not evenly matched and the fighting is limited to one country. There won’t be large-scale warfare dragging on for years – although low-level conflict might persist for years, as has been the case since Russia’s 2014 invasion of eastern Ukraine and Crimea.

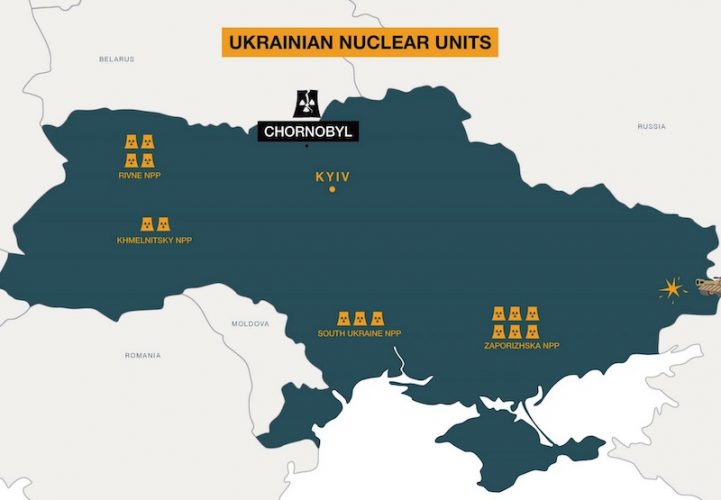

Ukraine does share one component of a worst-case scenario: its heavy reliance on nuclear power. Fifteen reactors at four sites generate 51.2 percent of the country’s electricity. It is one of only three countries reliant on nuclear power for more than half of its electricity supply.

A March 1 IAEA update, citing the State Nuclear Regulatory Inspectorate of Ukraine (SNRIU), said that all 15 reactors remained under the Ukrainian control and they continued to operate.

But in its daily post dated March 1, SNRIU lists six reactors as ‘disconnected from the power grid’, comprising three reactors at Zaporizhzhia and one each at the Rivno, Khmelnitsky and South Ukrainian nuclear power plants. Those disconnections amount to about 20 per cent of Ukraine’s total national electricity generation.

In the weeks prior to the February 24 invasion, 0-3 reactors were disconnected. The number rose to five on February 26 and has remained at six since then. It seems likely that the invasion has resulted in decisions to disconnect a number of reactors. Ukraine’s nuclear utility Energoatom cites “operational safety” for the disconnection of two reactors at Zaporizhzhia.

Even before the Russian invasion, Ukraine’s reactor fleet was ageing, its nuclear industry was corrupt, regulation was inadequate, and nuclear security measures left much room for improvement. For the time being, it is highly unlikely there will be any meaningful national or international oversight or regulation of the country’s ageing reactors and other nuclear facilities.

Deliberate or accidental military strikes on nuclear plants

A deliberate military strike on a power reactor is highly unlikely – but not inconceivable. Bennett Ramberg, a former foreign affairs officer in the US State Department’s Bureau of Political-Military Affairs, and author of the 1985 book Nuclear Power Plants as Weapons for the Enemy, draws this comparison:

“A case in point was the March 26, 2017, bombing of the Islamic State-held Tabqa Dam in Syria. Standing 18 stories high and holding back a 25-mile-long reservoir on the Euphrates River, the dam’s destruction would have drowned tens of thousands of innocent people downstream. Yet, violating strict “no-strike” orders and bypassing safeguards, US airmen struck it anyway. Dumb luck saved the day again: the bunker-busting bomb failed to detonate.”

An accidental strike is a troubling possibility. Or a strike disabling the vital power and cooling water supply systems which are necessary to maintain safety even after reactors are shut down.

Spent fuel cooling ponds and dry stores are vulnerable – they often contain more radioactivity than the reactors themselves, but without the multiple engineered layers of containment that reactors typically have.

And if there is an attack on a reactor or spent fuel store resulting in disaster, response measures would likely be chaotic and woefully inadequate. Forbes senior contributor Craig Hooper writes:

“It seems unlikely that Russia has mobilised trained reactor operators and prepared reactor crisis-management teams to take over any ‘liberated’ power plants. The heroic measures that kept the Chernobyl nuclear accident and Japan’s Fukushima nuclear disaster from becoming far more damaging events just will not happen in a war zone.”

Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant

The Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant is home to six reactors and lies near one of Russia’s main invasion routes, north of Crimea. As noted above, three of the six reactors have been disconnected in recent days.

The plant was contentious long before the recent invasion due to mismanagement and the ageing of the Soviet-era reactors. A 2017 Austrian government assessment of Zaporizhzhia concluded that: “The documents provided and available lead to the conclusion that a high probability exists for accident scenarios to develop into a severe accident that threatens the integrity of the containment and results in a large release.”

On February 28, Russia’s rt.com quoted a Russian Ministry of Defense spokesperson saying that “Russian troops have complete control and are protecting the territory around the … Nuclear Power Plant”. The spokesperson added that “station staff keeps working to maintain the facility and control the nuclear environment in normal mode.”

IAEA Director General Grossi said on March 2 that he thought Russian forces “are in control of the surrounding area and of the site as well. Which does not mean that they have taken over the plant itself, or the operation of the reactors. They have the physical control of the perimeter, including the village where most of the employees live.”

Grossi said that it is “imperative to ensure that the brave people who operate, regulate, inspect and assess the nuclear facilities in Ukraine can continue to do their indispensable jobs safely, unimpeded and without undue pressure.”

However there are reports of a civilian human blockade preventing or limiting Russian access to the Zaporizhzhia site. It seems unlikely that Zaporizhzhia staff have unimpeded access to and from the plant and their homes.

According to a March 2 SNRIU post, Russian troops have repeatedly attempted to capture the Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant but have been repelled by residents of the city of Energodar and the territorial self-defense forces. SNRIU states that missile shelling damaged the automated radiation monitoring system at Zaporizhzhia and repair of the system has been complicated by military actions near the plant.

Staffing

A single-reactor nuclear power plant typically employs 600-800 people. Presumably the workforce at the six-reactor Zaporizhzhia plant is considerably higher.

If not already, nuclear staff are likely to be killed when not at work, and others will flee and get as far away from the fighting – and the nuclear power plant – as they can.

If Russia’s military takes control of the site – and does so without causing a nuclear disaster – they could repeat what they have done at Chernobyl in recent days: keep Ukrainian staff hostage and force them to work under Russian control.

The most likely explanation for Russia fighting to take control of Chernobyl is simply that it lies adjacent from the invasion route between Belarus and Kyiv. And the most likely explanation for elevated radiation readings at Chernobyl is that the Russian military has disturbed residual contamination from the 1986 disaster.

The risks at operating nuclear power plants are considerably higher than the risks at the Chernobyl site, which contains high-level nuclear waste and the infamous stricken reactor #4 but no operating reactors.

Supply chains

Grossi commented on the importance of supply chains for nuclear safety, noting that vital supply chains should remain available to ensure that necessary services, equipment and components can be delivered to Ukraine’s nuclear facilities at all times, for example to carry out any emergency repairs.

Supplying diesel fuel for backup power generators in the event of a loss of grid connection is another supply chain issue of concern.

The adequacy of backup generators at Zaporizhzhia has long been a concern as detailed in a March 2 Greenpeace International report. In 2020, the Ukrainian NGO EcoAction received information from nuclear industry whistleblowers about problems with the generators at Zaporizhzhia, including a lack of spare parts.

In the same year, the regulator SNRIU reported on a generator malfunction. An upgrade of the generators was due to be complete by 2017 but the completion date has been pushed back to 2023, i.e. it remains incomplete.

Security at Zaporizhzhia was jeopardised in 2014 when an armed confrontation took place between security guards and paramilitaries from Ukraine’s ultra-nationalist ‘right sector’, allied with neo-Nazi groups. The gunmen wanted to ‘protect’ the plant from pro-Russian forces, the Guardian reported, but were stopped by guards at a checkpoint.

The head of SNRIU said in 2015: “I cannot say what could be done to completely protect [nuclear] installations from attack, except to build them on Mars.”

International monitors

Energoatom CEO Petro Kotin called on international monitors to intervene to ensure the safety of the country’s nuclear reactors and to create 30km exclusion zones around the four nuclear power plants.

Energoatom noted in a statement that columns of military equipment have been moving near nuclear power plants with “shells exploding near the nuclear power plant – this can lead to highly undesirable threats across the planet”.

The Acting Chief State Inspector of SNRIU has asked the IAEA to provide immediate assistance in coordinating activities in relation to the safety of nuclear facilities. The IAEA noted that Director General Grossi “will be holding consultations and maintain contacts in order to address this request”.

But the request for assistance in establishing an exclusion zone has been rejected by the IAEA. “The IAEA has no power to enforce an exclusion zone,” Grossi said following an emergency IAEA session on March 2.

Grossi continued:

“Ukraine is a member state of the IAEA, and they are entitled to, and expect to get assistance when there is a problem, in this case related to the safety of their facilities. Obviously in the present circumstances, delivering assistance is not a straightforward or easy process. This is why I am in contact with all sides to ascertain in which effective way we could be providing assistance. Since these consultations are ongoing I would not be in a position right now to say what kind, or when, this assistance will be delivered.”

Canada and Poland have submitted a draft resolution to the IAEA condemning Russian aggression near the nuclear plants. US deputy ambassador Louis Bono said:

“These are extraordinary circumstances, and Russia’s actions directly threaten the IAEA’s core missions of nuclear safety, security, and safeguards. We view with grave concern Russian armed forces in the vicinity of Ukraine’s nuclear power plants, and in particular claims that its armed forces control the territory around the Zaporizhzhya facility.”

Nuclear waste

The report by Greenpeace International nuclear specialists notes that as of 2017, Zaporizhzhia had 2,204 tons of spent fuel in storage at the site – 855 tonnes in the spent fuel pools within the reactor buildings, and 1,349 tonnes in a dry storage facility.

The spent fuel pools contain far more radioactivity than the dry store. Without active cooling, the pools risk overheating and evaporating to a point where the fuel metal cladding could ignite and release much of the radioactive inventory. Damage to the reservoirs which supply cooling water to Zaporizhzhia could disrupt cooling of reactors and spent fuel.

The Guardian reported in 2015 that the dry store at Zaporizhzhia is sub-standard, with more than 3,000 spent nuclear fuel rods in metal casks within concrete containers in an open-air yard close to a perimeter fence.

Neil Hyatt, a professor of radioactive waste management at Sheffield University, told the Guardian that a dry storage container with a resilient roof and in-house ventilation would offer greater protection from missile bombardment.

Cyber-warfare

Cyber-warfare is another risk which could jeopardise the safe operation of nuclear plants. Russia is one of the growing number of states actively engaged in cyber-warfare. James Acton from the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace notes that a Russian cyber-attack disrupted power supply in Ukraine in 2015.

Nuclear facilities have repeatedly been targets of cyber-attack, including the Stuxnet computer virus targeted by Israel and the US to disrupt Iran’s uranium enrichment centrifuges in 2009.

Reports from the UK-based Chatham House and the US-based Nuclear Threat Initiative have identified multiple computer security concerns specific to nuclear power plants.

Waste storage and disposal sites

Missiles hit a radioactive waste storage site near Kyiv on February 27. The IAEA stated in a March 1 update:

“SNRIU said that all ‘radioactive waste disposal facilities of the State Specialized Enterprise Radon were operating as usual, and the radiation monitoring systems did not indicate any deviations from normal values. On 27 February, the SNRIU informed the IAEA that missiles had hit the site of such a facility in the capital Kyiv, but there was no damage to the building and no reports of a radioactive release.”

The Kyiv radioactive waste storage site appears to be at least 1 km from any other human structures, suggesting the possibility of a deliberate strike.

Also on February 27, an electrical transformer was damaged at a radioactive waste storage site in Kharkiv, also without any reports of a radioactive release. According to SNRIU, a research reactor at the site has been shut down.

Grossi said: “These two incidents highlight the very real risk that facilities with radioactive material will suffer damage during the conflict, with potentially severe consequences for human health and the environment. I urgently and strongly appeal to all parties to refrain from any military or other action that could threaten the safety and security of these facilities.”

The Kyiv and Kharkiv facilities typically hold disused radioactive sources and other low-level waste from hospitals and industry, the IAEA said, but do not contain high-level nuclear waste. However the Kharkiv site may also store spent nuclear fuel from the research reactor.

Dr. Jim Green is the national nuclear campaigner with Friends of the Earth Australia.