Though the root cause of the catastrophic failure of a turbine at the Callide C coal plant in Queensland is yet to be determined, there is one unambiguous certainty: it’s already drawn focus on one of the biggest issues in Australian energy and climate policy, and one of the most strangely underdiscussed.

We know, now, that the turbine at Callide C suffered damage far more serious than may have been initially assumed. What I read as a ‘fire in the turbine hall’ initially seems like the rapid unscheduled disassembly with genuinely dangerous consequences.

Mark Ludlow in the AFR quoted CFMEU district president Shane Brunker saying that there are “holes punched in the roof and walls and the shielding of the building”, and that “there was a piece of metal in the roof. We didn’t know what it was, but it weighed 300 kilograms”.

There is a picture doing the rounds on social media that is purportedly (and likely) of the wreckage of the plant, but it has been difficult to confirm with certainty. Regardless, the thing is ruined. And despite some speculation that the Queensland government part-owners of the plant may opt to shut it down permanently and replace it with a battery and/or renewable energy, the plan is officially to re-construct the turbine unit, at a cost of many hundreds of millions of dollars, and over at least a year, if not longer.

“CS Energy’s intention is to replace the unit. You need the coal there to enable the transition. You need the blend,” CS Energy CEO Andrew Bills told the AFR. “Callide C is one of the youngest coal-fired generators in the NEM and features high-efficiency super-critical boiler technology. It operates at a higher efficiency and has lower greenhouse emissions compared to most coal-fired power stations in Australia”.

There was certainly never any chance of any other outcome. On April 21 this year, Stanwell’s then CEO flagged an option to reduce the output of coal power in Queensland to make room for zero emissions sources. By April 27 he was gone. Merely uttering the possibility of reduced coal output is, literally, a sackable offence in Queensland.

Of course, it is not true that coal is “needed” in an energy transition. Australia’s grid is bloated with coal – there is an incredible amount. So much so that Australia is a world leader in the proportion of coal in the grid. Nowhere in the world ‘needs’ coal, and to make matters worse, burning coal releases greenhouse gas emissions. Which cause climate change.

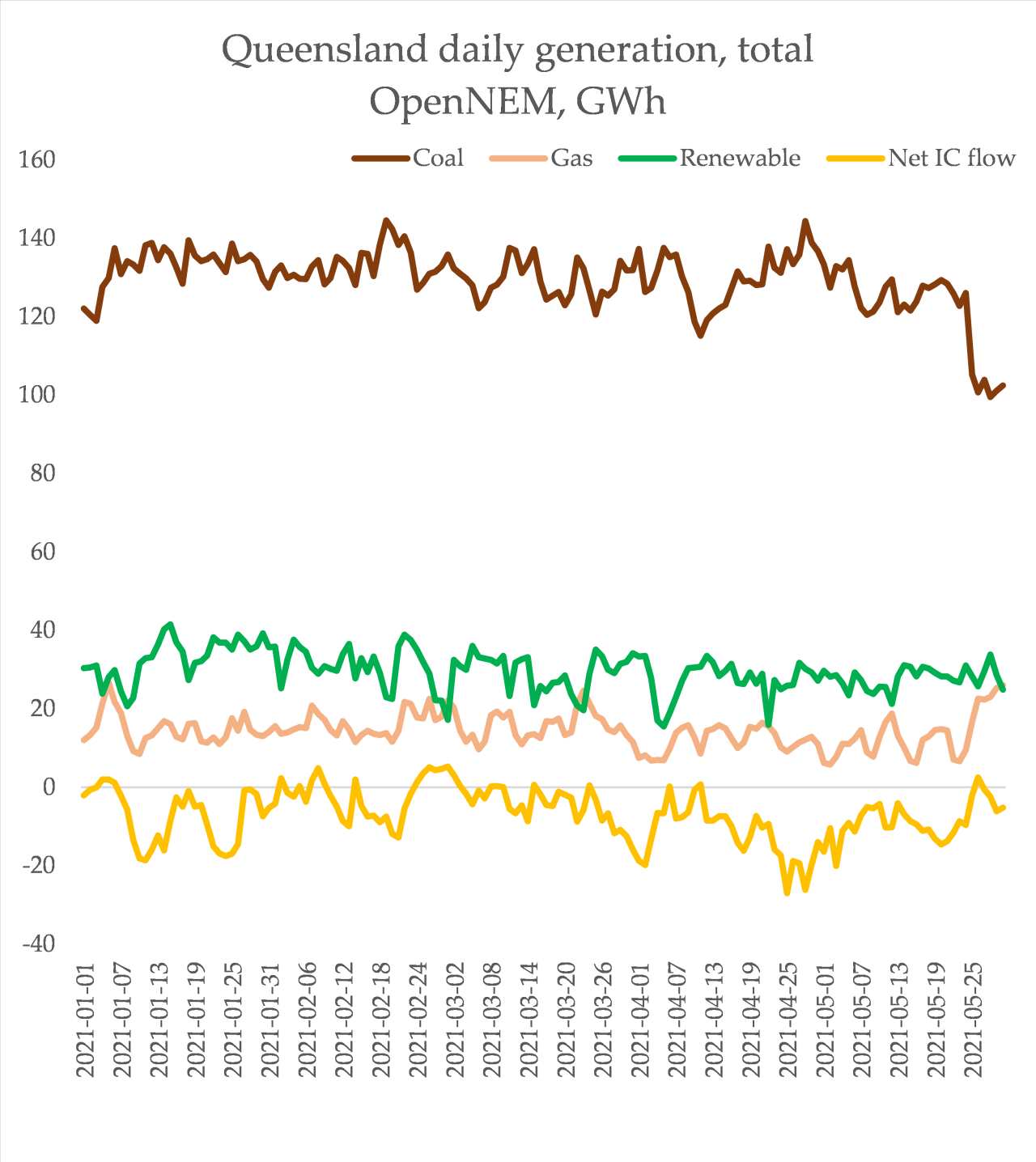

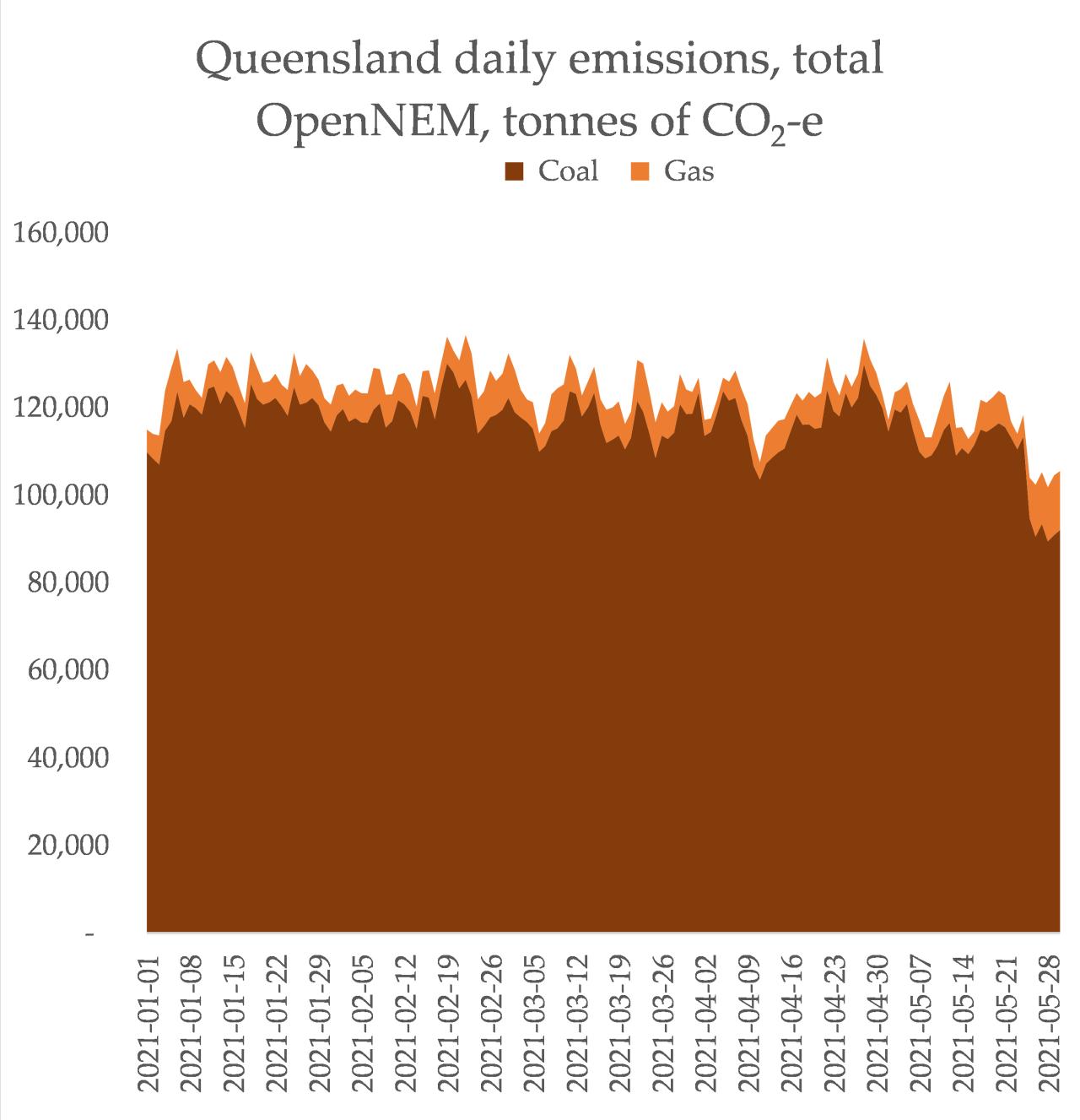

After the Callide C coal plant explosion, another three units at the plant went offline, and now they are not due back for another few weeks. Gas-fired generators in the state have ramped up to fill the gap, along with reduced net export flows to other states (wind, solar and hydro have remained steady).

As a consequence, Queensland’s total emissions have fallen – with around half of the drop in emissions from coal cancelled out by the emissions from the rise in gas generation:

Queensland has a long-lasting coal problem

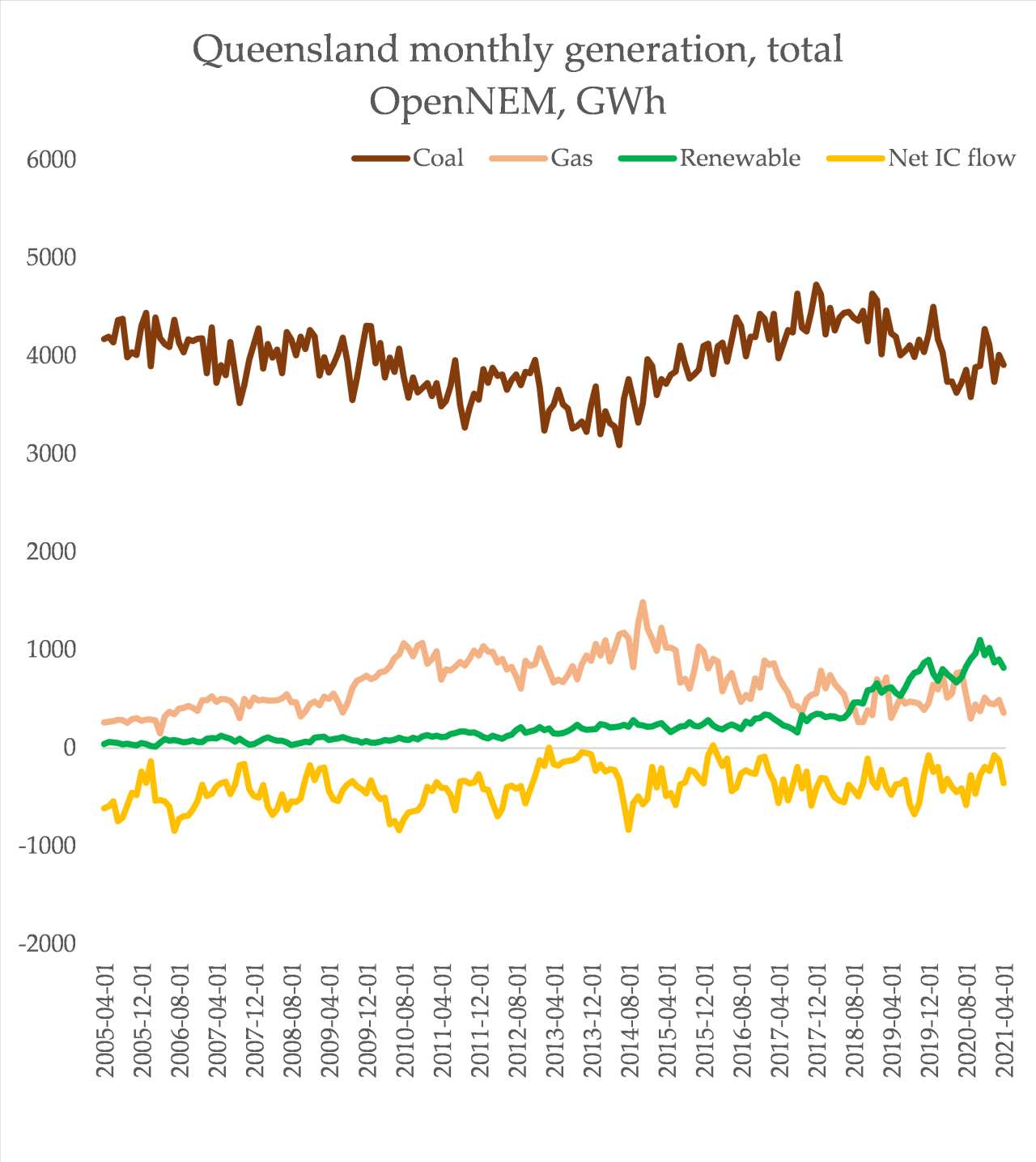

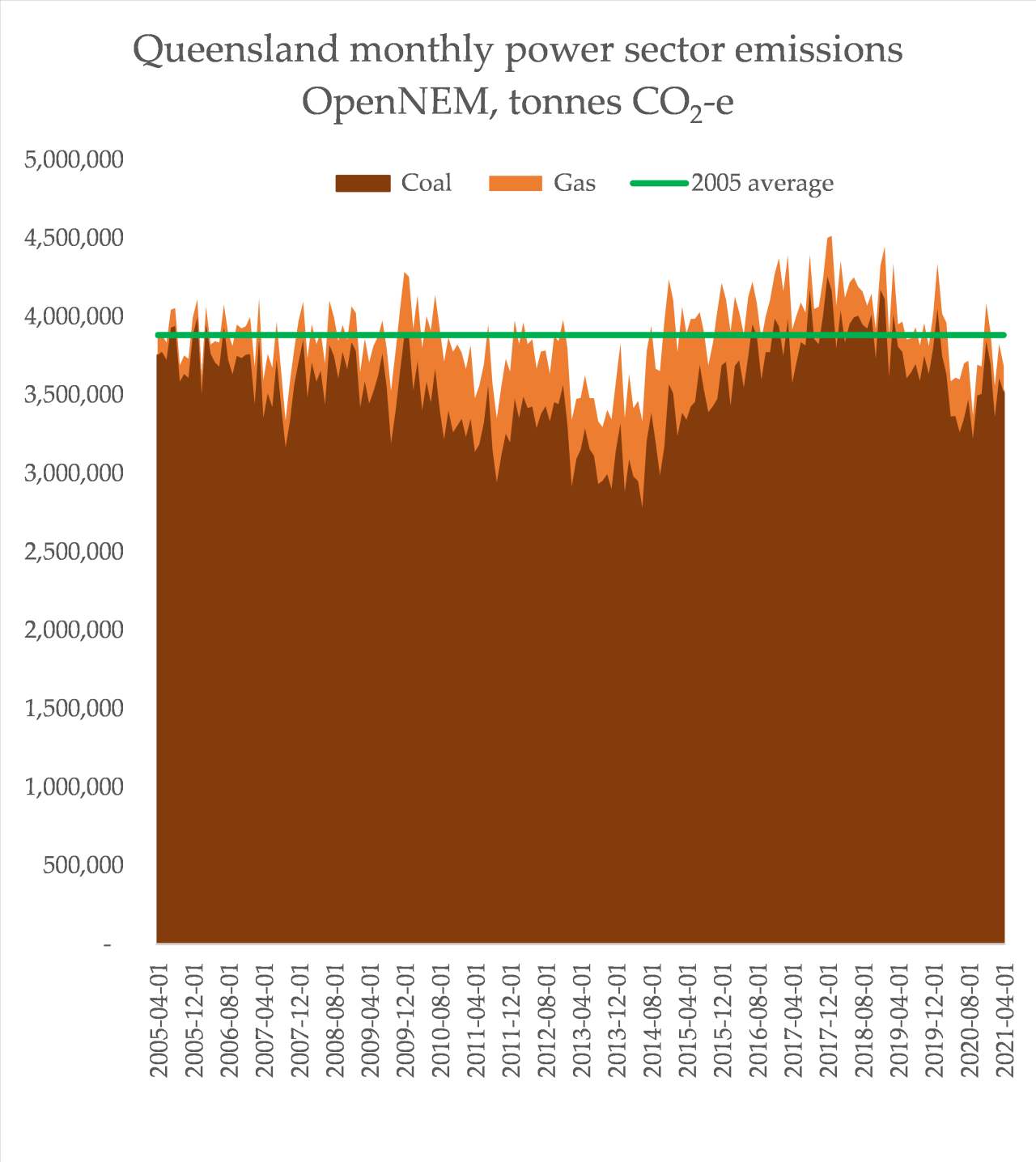

Since 2006, renewable energy has grown from around 0.7 terawatt hours to 9.9 terawatt hours in Queensland, growth driven entirely by wind and solar. Coal power has fallen from 50 terawatt hours in 2006 to 47, in 2020. Wait. What? In 2018, coal output was even higher than 2006, at 53 TWh.

The growth of renewable energy has almost entirely been displacing gas-fired power in Queensland. While this definitely reduces emissions, it isn’t reducing emission as much if it was coal that was being displaced. The incredible consequence: Queensland’s emissions remain at or – generously – slightly below their 2006 level, despite a ~10x growth in renewable energy in the state.

The rate at which coal plants close is the most significant short-term determinant of Australia’s entire short-term domestic emissions trajectory. They are the largest single source of greenhouse gases in Australia, and many other countries. Shutting them down before 2030 is critical to laying the groundwork to decarbonise the rest of society by 2050.

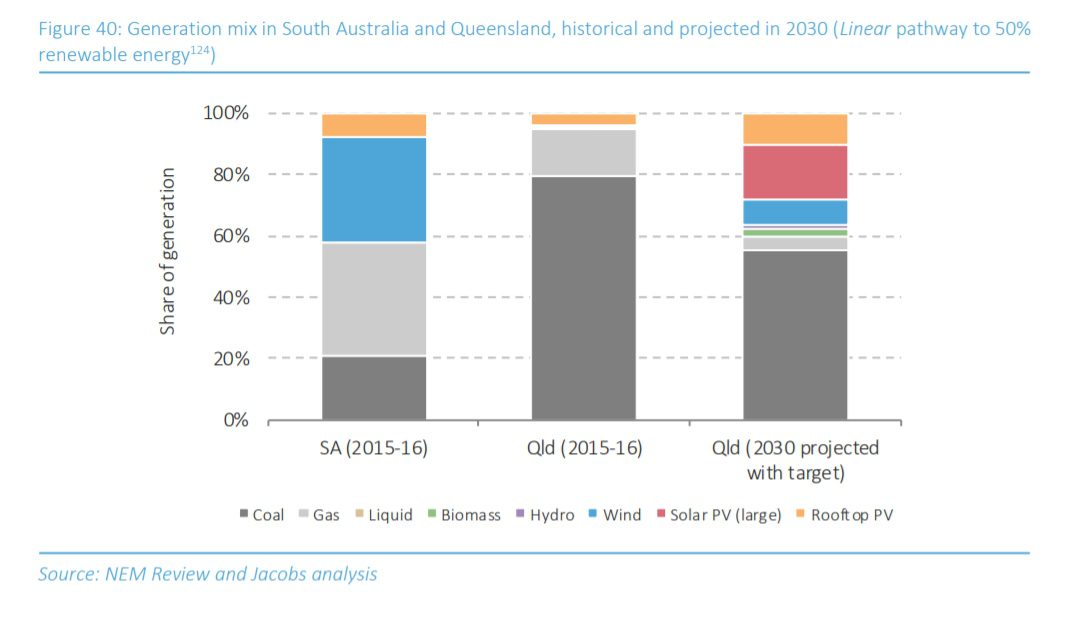

In 2017, Queensland’s government commissioned a study into pathways to delivering 50% renewables by 2030. While it gently touches on the idea of early coal retirements, it ultimately shuns the concept. “On balance, the panel does not see a 50% renewable energy target driving the early retirement of coal-fired generation plant in queensland”.

“In contrast to the South Australian experience, in Queensland coal generation is expected to continue to play a significant role to 2030 under a 50% renewable energy target……no closures are projected in Jacobs’ modelling as the result of the introduction of a 50% renewable generation target in Queensland”.

“In contrast to the South Australian experience, in Queensland coal generation is expected to continue to play a significant role to 2030 under a 50% renewable energy target……no closures are projected in Jacobs’ modelling as the result of the introduction of a 50% renewable generation target in Queensland”.

Only a few years since that modelling, it’s already badly obsolete. A variety of international climate and energy groups are calling for the end of coal-fired power by 2030, to align with the world’s 1.5°C Paris Climate agreement goals. And the space inbetween is surely due to the plagued by the various problems that arise operating inflexible, unreliable and outdated technology among new, flexible forms of energy.

In Australia, not only has the Paris Climate agreement been forgotten, climate change and emissions are rarely considered and barely mentioned when it comes to discussions around the future of coal plants. When we re-focus on the problem at hand, it becomes incredibly clear that spending millions to refurbish something that’ll cause significant harm through its greenhouse gas emissions – when cheap, clean alternatives exist and are ready to deploy – is folly.