It is well known that the so-called Tesla big battery in South Australia was the biggest lithium-ion battery in the world when it began operations in late 2017. But it’s about to be dwarfed by a new generation of big batteries, both in terms of capacity and storage as the market dynamics change along with the increase in large scale wind and solar, and rooftop installations.

When Hornsdale was first installed, the 100MW/150MWh installation did indeed seem big: After all, the Australian Energy Market Operator had predicted just a year earlier that the biggest battery we would likely see on the main grid would be sized around 1MW. Battery storage, we were told, was ten to 20 years away from making a significant contribution.

How things change. And how quickly. Not only did the Tesla and the other big batteries that followed prove skeptics wrong by being faster, quicker, more accurate, more reliable and more flexible than everyone thought possible, they have also begun delivering services many thought they couldn’t do.

And now they are getting bigger, too.

The Tesla big battery – officially and now more commonly known as the Hornsdale Power Reserve (because there are now a few other Tesla big batteries around the place) – was expanded last year to 150MW/194MWh, but around the same time lost its “biggest in the world” title.

Later this year, Hornsdale will lose the “biggest in Australia” title too, as its owner Neoen puts the finishing touches to the 300MW/450MWh Victoria big battery near Geelong. But it won’t be long until that too is surpassed, as even bigger batteries with longer duration storage take centre stage.

There are a couple of reasons for this development. To date, big battery installations have mostly been focused on delivering network services to the grid – frequency control, synthetic inertia and as “virtual synchronous machines”, where they have shown they can replicate, and even out-perform, the synchronous qualities of coal and gas plants. And to do this job they have only needed to have short duration storage, often half an hour or less.

Because of this, the big batteries installed to date have actually been doing very little of what most people would understand as energy storage – time shifting excess wind and solar output to times of the day when it might be more useful.

That’s mostly because it hasn’t been needed. As the Australian Council of Learned Academies (ACOLA) reported a few years ago, and as many other studies have also concluded, storage is probably not needed for a major grid until the level of wind and solar reaches around 50 per cent.

That’s mostly because the market operator can still rely on the back-up power that was installed to support the fossil fuel generators that dominated the grid for so long. And it also explains why most of the pumped hydro storage in Australia that was built decades ago is still rarely used.

But as the amount of wind and solar continues to grow, and as the retirement of ageing and inflexible coal and gas assets accelerates, the opportunity for time shifting wind and solar is emerging.

Over the last few months the number of battery storage projects looking at up to four hours of storage, where they will shift wind and solar production into the evening peaks, is growing rapidly.

Chief among these are some of the biggest coal generators in the country – including EnergyAustralia, Origin Energy and AGL.

EnergyAustralia is planning a 350MW big battery with four hours storage at Yallourn in Victoria, which is due to close in 2028. AGL is building a 250MW big battery with up to four hours storage at Torrens Island in South Australia, where it is closing and mothballing ageing gas units, and also plans a similar installation at the site of the Loy Yang coal generator in Victoria. Origin is looking at a big four-hour battery at Eraring, which will also close in a decade.

So, too, are other renewable energy developers, such as Tilt in the Latrobe Valley

One of the key bits of data they are looking at is volatility in the market. Storage of any type is only profitable if the battery can charge, or the hydro pump, when prices are low, and discharge or sell when prices are high.

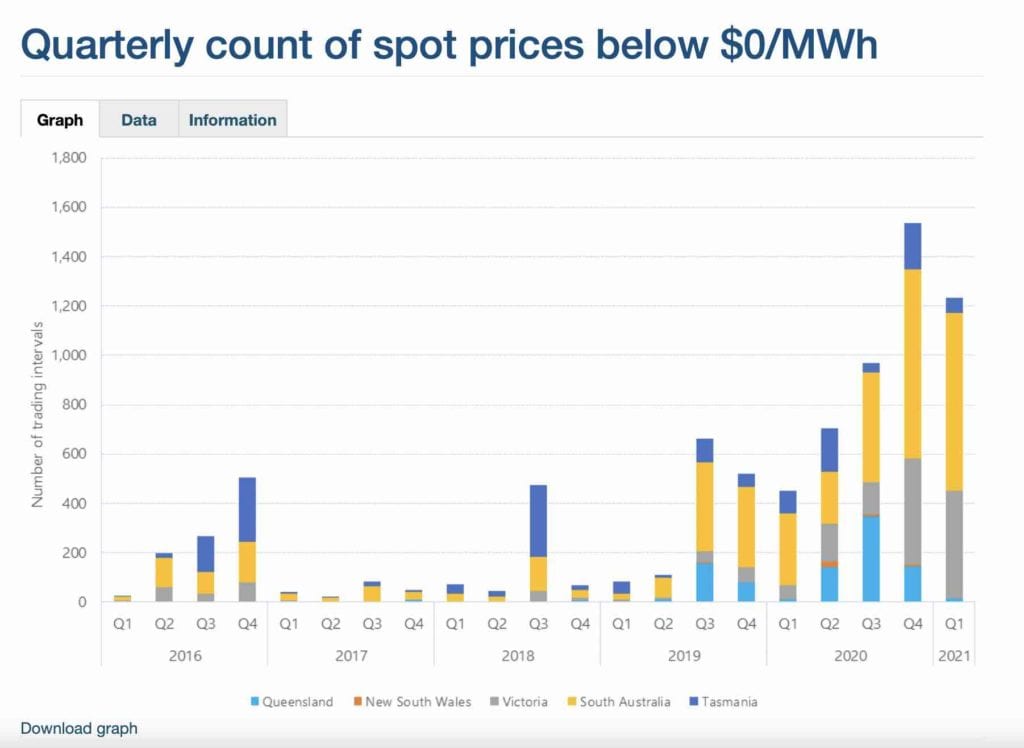

One of key indicators is the number of negative spot pricing events. This used to only occur at night-time when coal generators competed vigorously so they didn’t have to switch off. Now the occasions have multiplied, particularly in daytime hours, and as a result of excess solar or wind generation at times, or grid constraints that restricts the opportunity for output to be shared with other states.

The first to market with a four hour battery, however, may be Alinta Energy. And interestingly, it will not be happening on the main grid where many states have ambitious renewable energy targets, it will be happening in the Pilbara mining province, where big miners such as Fortescue, BHP and Rio Tinto are serious about cutting emissions from their operations.

Alinta is proposing a 30MW/120MWh battery at Port Hedland, where it operates a gas generator that supplies its big mining customers, and is looking to install a 90MW solar farm to respond to their desire for cleaner, and cheaper electricity.

Alinta says the battery will have a dual-role, smoothing out the solar output and time shifting some of it for use in the evening peak. And then, at night time, the battery will store the output of the gas generator output, allowing those turbines to operate at full capacity and then be switched off as the battery takes centre stage.

Alinta says that increase efficiency will cut both costs and emissions, and mean that the battery can pay for itself within a few years, as the smaller battery at Mt Newman has done on a separate network serving several iron ore mines.

In an interview on this week’s episode of the RenewEconomy podcast Energy Insiders, Alinta’s head of asset strategy gary Bryant says the Port Hedland battery ends up in a slightly different configuration – 60MW and two hours storage, for instance – depending on the quotes from suppliers and the details of the market opportunity.

“It comes down to what are the construction costs from the suppliers out there, they’re all kind of honing in on specific models in order to reduce their costs of production in order to make the the overall construction cost lower and more competitive,” Bryant said.

“Charging and discharging a battery at 30 megawatts, which is kind of the average unit size for a gas turbine and Port hedland, that’s where you end up with that, that that four hour battery size.

“So it’s more to do with the amount of energy that we need to store rather than a particular amount of storage time, if that, if that makes sense.”

Bryant says putting in such a battery in a market like the Pilbara makes sense because the gas generation keeps the average cost high.

The challenge for battery storage in the broader market will be to make the arbitrage work in a grid still dominated by coal fired generation. But the increasing amount of wind and solar, the increasing pressure on fossil fuel generators, and the shift to five minute settlements, should make this easier.

And all eyes will be on the final recommendations of the Energy Security Board and its proposed re-write of the market rules, the first extensive review in more than two decades.

Will it, as promised, reflect and encourage the shift to new faster, smarter and more flexible technologies such as battery storage, and demand management, or will the battle be won by a few remaining incumbents, and the federal government, still deeply attached to the technologies of the past.