Australia produces five times as much methane as our population should warrant, according to new data from the International Energy Agency (IEA) – systemic underreporting means that number is likely to be much, much higher.

Methane emissions hit 5544 kilotons in 2022, or 1.6 per cent of the global total, despite Australia having just 0.3 per cent of the world’s population.

The largest share of methane emissions came from agriculture — burping cattle and sheep to be specific — but it is closely followed by the energy sector with all forms of coal being the chief culprit.

Last year, the IEA said methane emissions from energy globally were 70 per cent higher than companies’ official data indicated.

“While farmers in Australia are working to reduce the methane from their livestock, we have not seen the same initiative from the coal and gas sector. Plans to expand coalmining would lock in these uncontrolled emissions for years to come,” said the Australian Conservation Foundation’s climate and energy campaigner Suzanne Harter.

“Satellite data has found some coal mines emit significantly more methane than they report.

“There are strong indications companies are underreporting methane emissions, often relying on estimates rather than direct measurement.”

Indeed, in Australia allegations have already been flying about a coal industry emissions coverup.

In November last year independent MP Andrew Wilkie alleged in Parliament that major coal players, an investment bank, a global accounting firm and two multinational testing companies were implicated in a “scam” to inflate the “cleanliness” of its coal, by saying it was drier and therefore burned cleaner than it actually did, and paid bribes to overseas parties to maintain secrecy.

However, according to data from methane tracker Kayrros also released in November, Australia is the only country which has pledged to reduce methane emissions to have made headway on that aim, largely due to reductions in the Bowen coal basin.

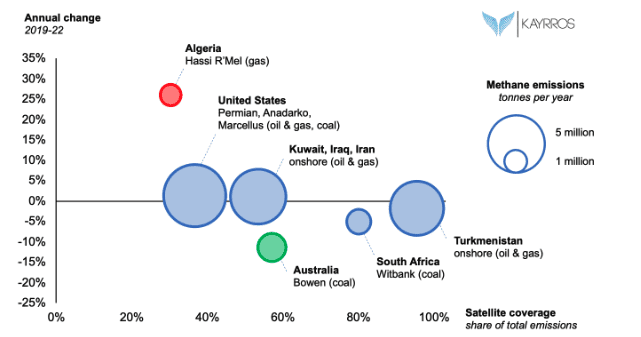

Methane inventories in select fossil fuel basins (size of bubble = Mt CH4/yr), coverage of satellite data (x-axis, relative to total country emissions) and annual trend rate since 2019 (y-axis).

“Emissions from Australia’s Bowen basin have declined by approximately 11 per cent per annum,” Kayrros said in its pre-COP27 report.

Australia only took the COP26 pledge in October last year, just before COP27 in Egypt. The pledge is to bring down methane emissions by 7 per cent a year and 30 per cent cumulatively by 2030.

Methane is a more potent gas than carbon dioxide: although it only lasts about 12 years before breaking down into carbon dioxide, it is more than 80 times as damaging to the atmosphere and responsible alone for 30 per cent of global warming to date, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Underestimating methane emissions is rife

Estimating emissions is becoming a more accurate science, with the advent of satellite-based monitoring such as that by Kayrros, but a surfeit of research is emerging to show by just how much companies and governments have been underestimating the problem — either in the planning of projects or while in operation.

SRON Netherlands Institute for Space Research satellites show Glencore’s Hail Creek coal mine in Queensland emits 10 times as much methane as the company reports, some 200,000 tonnes annually.

A year ago the Australian Conservation Foundation found that Chevron released 16 million tonnes more greenhouse gases, including methane, from the Gorgon project in Western Australia than the company said it would during the approval phase.

Coal miner Whitehaven underestimated emissions from its Maules Creek and Narrabri coal mines by two to four times.

“We found that estimated emissions during the approval phase is not a good predictor of actual emissions,” the report said.

“We found that two in three fossil fuel projects were wrong about their estimates by more than 25%. In some scenarios, this includes projects that actually emitted less than anticipated. But most concerning, we found that one in three fossil fuel projects are emitting more than estimated during the approval phase.”

Fugitive and vented emissions from the oil gas industry are the next biggest problem after all coal emissions, according to the IEA.

Data from the University of Michigan last year showed methane emissions from flaring, or burning off gas at oil and gas wells, are five times higher than currently thought.

“Flaring is often not as efficient as presumed—or methane plumes simply are not combusted at all,” the researchers found.

In the UK, energy sector methane emissions are suspected to be 40 per cent higher than anyone thinks.

Biggest polluters pay the least tax

If oil and gas companies are underestimating their emissions, they’re also making sure their tax bills are equally as small.

Tax data shows Santos paid no income tax between from 2015 to 2018 and 2020 and just $6 million on $28.9 billion on income in fiscal 2021, according to The Australia Institute (TAI). Despite the lack of tax paid on other projects, this month the Western Australia government approved Santos’ latest project in the north of the state, the Dorado oil and gas fields.

Shell has paid no income tax since 2015. Contrary to its own forecasts of paying $12 billion in taxes on its Prelude floating LNG terminal, it now says it will never pay Petroleum Resource Rent Tax on the project, a tax levied when a company’s profits exceed its losses.

The TAI analysis showed APPEA’s claims of $11.2 billion in taxes coming in from Queensland coal seam gas companies to be false, as those companies have paid almost no taxes. And in 2015 Chevron estimated it would have paid around $4 billion in “direct taxations and royalties” by 2020. It has paid no income tax or resource tax over that period.