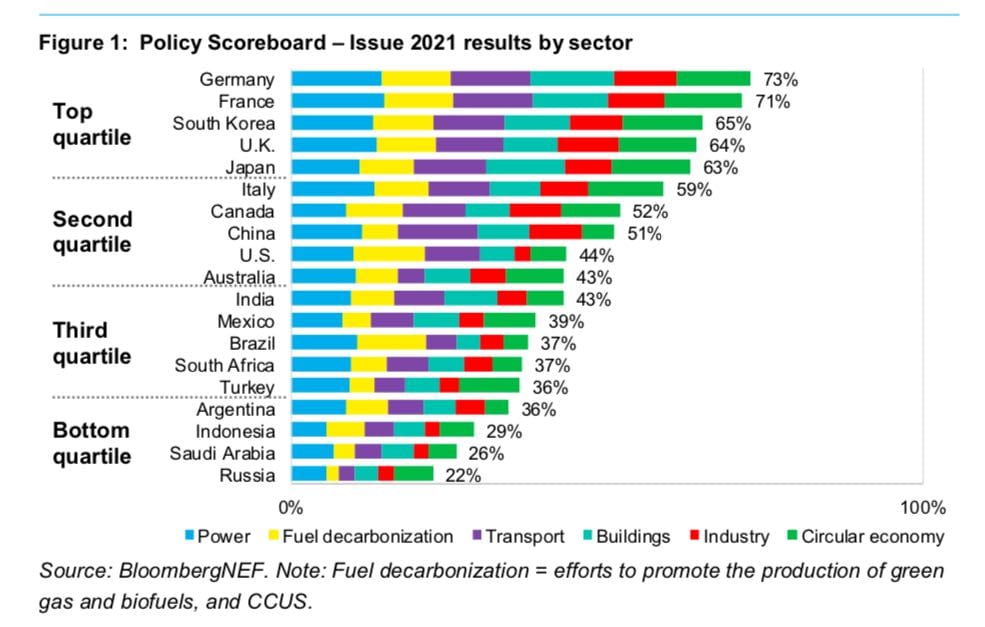

Australia has the weakest climate policies of the largest developed economies in the world, behind the likes of Germany, France, the UK, Canada, Italy and even the US, according to a new assessment from Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

BNEF’s newly published G20 Zero Carbon Policy scoreboard, which grades the climate policies of the world’s 20 biggest economies, put Australia in 10th position, ahead only of countries with economies traditionally considered developing.

China, the world’s biggest greenhouse gas emitter, received a higher overall score for its climate policies than Australia, as did South Korea and Japan. With a score of 43 per cent, Australia was on a par with India, and just ahead of Mexico and Brazil, but below the average.

Germany topped the list with a score of 73 per cent, while Russia was the worst performer, on 22 per cent.

Australia’s rating on transport was especially poor, coming third last ahead of only Saudi Arabia and Russia – a reflection of the continued lack of any national policy to encourage the uptake of electric vehicles.

The scoreboard looks at policy in six areas: power, fossil fuel decarbonisation, transport, buildings, industry, and the circular economy. It grades countries out of 100, based on 122 “qualitative and quantitative metrics relating to the number, robustness and effectiveness of policies”.

Australia’s best results were in power – thanks to the rapid growth of renewable sources of electricity generation – and the circular economy. But even there it was far behind the top performing European and East Asian countries.

Overall, BNEF said the results of the study were not encouraging, saying nations were “far from having the right policy plans in place” to meet the Paris goal of keeping global warming well below 2 degrees and as close to 1.5 degrees as possible.

“The high-level pledges over the last year, in particular, have been impressive with major economies such as the European Union, Japan, South Korea and China all promising to get to ‘net-zero’ emissions or carbon neutrality at some future date,” said Victoria Cuming, head of global policy analysis for BNEF.

“But the reality is that countries simply haven’t done enough at home with follow-through policies to meet even the promises made more than five years ago.”

Overall the average score was 47 per cent, meaning Australia’s 43 per cent was well below average. The power sector, which is where some of the lowest-hanging fruit of decarbonisation are found, was the highest, with an average score of 58 per cent.

But Cuming said countries were putting too much emphasis on the power sector, and neglecting other sectors.

“While some power-sector policies have delivered results, most countries have done little elsewhere in the economy. And even within each sector, it’s not enough to implement incentives for one technology – multiple pathways are required,” she said.

The study stressed the need for carbon pricing, something Australia’s Coalition government has ruled out introducing. It also focused on the need to abandon fossil fuel subsidies, but found Australia’s had grown over the last decade.