Australia’s fleet of big battery projects is growing quickly – in number, size and duration – and the primary source of market revenue is also rapidly evolving.

When the first big batteries entered the grid in 2017 with the arrival of the Tesla big battery at Hornsdale, the initial focus was on the frequency control and ancillary service market, a highly lucrative sideline that was the cream on top of the fossil fuel generator’s business pie.

The new big batteries quickly smashed that particular cartel, particularly in states like South Australia that had little competition in the market, but that was never going to sustain them.

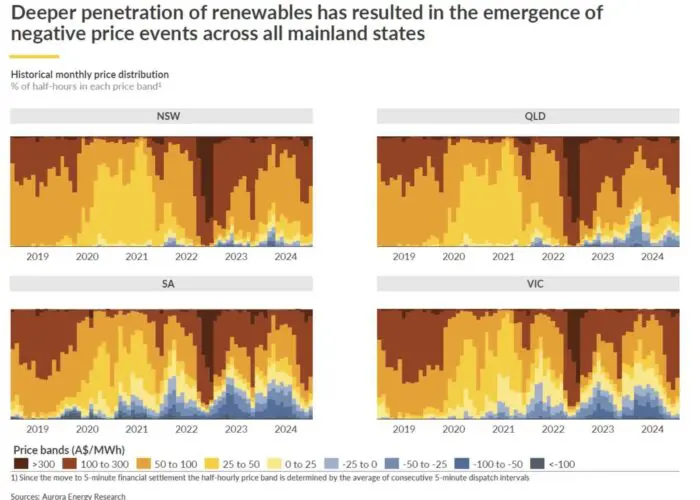

Now, with the increased penetration of wind and solar, and increased volatility in the wholesale electricity markets, the focus has switched to energy arbitrage – the money to be made from charging at low or even negative prices (being paid to charge), and sending it back into the grid during demand peaks when prices are high.

That has now become the dominant revenue stream from market activities for the fleet of big batteries, and helps explain why the storage duration – initially focused on around one to 1.5 hours – has quickly evolved into a two hour minimum and often four hours or more.

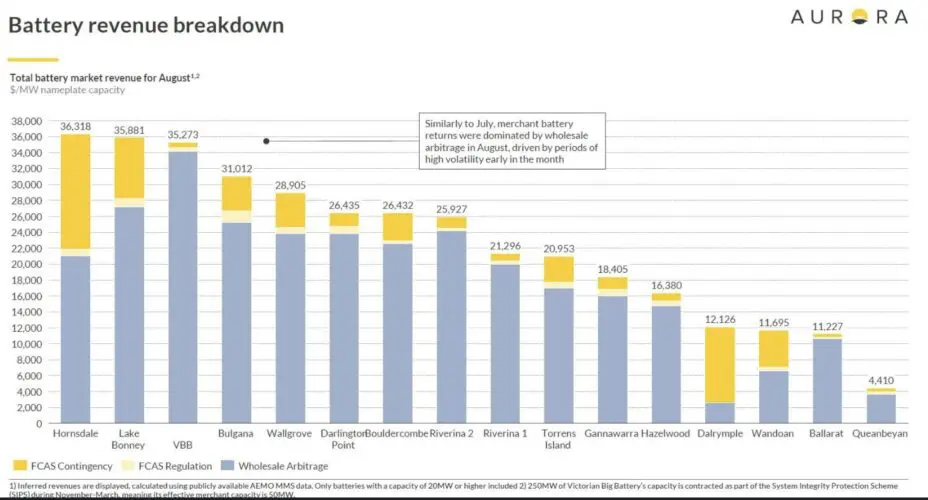

This graph from the international energy analyst company Aurora shows the extent that this has changed, with arbitrage (in blue) considerably bigger than FCAS revenue (in yellow).

Of course, this is not the only source of revenue for the big batteries – many have sometimes very lucrative contracts for providing other grid services, mostly related to supporting increased network capacity and, soon, also time shifting of rooftop solar in W.A.

It is interesting to note that the only big battery that still has most of its income sourced from FCAS is the Dalrymple North battery in South Australia.

That’s easily explained by the fact that is has only limited storage – at 30 MW and 8 MWh it has barely 15 minutes of storage and its role is primarily to keep the frequency steady on its edge of grid location on the Eyre Peninsula, and also act as the primary provider should the power be cut by faults elsewhere.

“The shift away from FCAS is especially striking for the other SA assets, Hornsdale and Lake Bonney. Last financial year, they made about 60% of their revenue from FCAS,” says Aurora’s head of research in the Asia Pacific James Ha.

“Two factors explain the shift. The first reason is a greater arbitrage opportunity. We’re seeing wholesale prices hollow out, with markets clearing more regularly below $0 or above $100/MWh (see graphs below).

“The second reason for the shift is that the competition for FCAS revenues is becoming more fierce. We now have almost 2GW of utility-scale batteries in the NEM chasing FCAS markets that are on average less than 600MW deep.

“We expect wholesale arbitrage to dominate most batteries’ revenue stacks moving forwards, except during system events that lead to frequency separation between parts of the NEM (which can occur during transmission line outages, for instance).”