Despite the Coalition’s best efforts to pour cold water on Australia’s transition to a low-carbon power network, things are really hotting up in the clean energy sector.

Despite the Coalition’s best efforts to pour cold water on Australia’s transition to a low-carbon power network, things are really hotting up in the clean energy sector.

Latest data from Bloomberg New Energy Finance reveals a “record-smashing” year for investment in solar and wind in Australia in 2017, totalling $A11.2 billion ($US9 billion) and propelling the nation to 7th position on the world leader board.

Driving this tidal wave of investment in the Australian market – a 150 per cent improvement on 2016, according to BNEF – has been the industry scramble to meet the federal government’s Large-scale Renewable Energy Target, as well as the groundswell of consumers seeking solutions to rising power prices.

Standout figures from the BNEF Australia report include $US7.5 billion investment in 4.2GW of large-scale projects, up 222 per cent from 2016; and $US1.5 billion investment in small-scale clean energy, an 18 per cent improvement on the year before.

“2017 was a breakout year for the Australian Clean Energy sector. Total investment in clean energy in Australia rose to a record $US9 billion, smashing the previous record of $US6.2 billion set in 2011,” said Leonard Quong, a senior analyst with Bloomberg New Energy Finance in Sydney.

But just as the race to meet the RET – 33,000 gigawatt-hours of additional renewable energy generation by 2020 – has helped drive the current boom in clean energy investment, its fulfilment could see investment go off a cliff, with nothing but the Turnbull government’s proposed National Energy Guarantee to cushion the fall.

Says Quong: “2017 will likely mark a peak – investment will begin to taper over the coming years unless there is a significant change in government policy.”

The issue, explains BNEF’s head of Australia, Kobad Bhavnagri, “is that the NEG, as currently devised, is slated to achieve just the 26-28 per cent emission reduction target by 2030.

“For the power sector alone, that is a very weak target. …By our calculation, the NEG would require only about 1.5GW of large-scale renewable energy to be constructed over the coming 10 years to achieve the 26-28 per cent target.

“So what’s required is a more ambitious emissions reduction target under the NEG, or for state governments to continue to develop policy to ramp up investment,” Bhavnagri told RenewEconomy in an interview.

In particular, he added, the focus would be on Queensland and Victoria – two states that have “already been a sort of lifeline to the industry.” Other states, namely NSW, would have to lift their game.

But it might not have to come down to the states, going it alone.

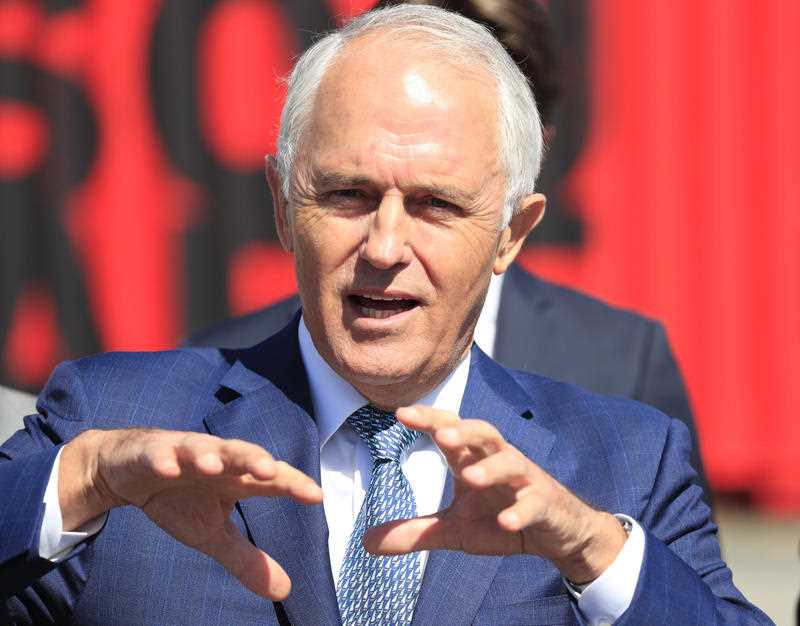

Bhavnagri has not written off the possibility that the Coalition will come to the party on more ambitious, longer-term emissions targets – not just to drive investment in renewables; not just because the growing policy chasm between Canberra and the states is starting to make Malcolm Turnbull look really bad; but because that is what Australia signed up for when it joined the Paris climate accord.

“I think this is a key thing to watch in 2018,” Bhavnagri told RE. “Because every state and territory in the NEM has signed up to targets (more ambitious than the federal government’s).

“States should be throwing their weight around the COAG table and only signing up to a NEG if it ups ambition on a pathway to net zero emissions by 2050,” he said.

“That’s the only viable option,” he says, if Australia is truly committed to the global climate goal of restricting warming to less than 2°C.