As the world’s leading exporter of iron ore, Australian miners face a raft of risks and opportunities as steelmakers decarbonise their operations, but there remains a lack of certainty over exactly which technological pathway will lead to low carbon steel.

These are the headline findings from a new report from energy analysts BloombergNEF (BNEF) which analyses how trade dynamics are expected to shift as the global steel supply chain transitions to low carbon, and how Australia and its trading partners can cement their foothold in the global decarbonised steel supply chain.

While Australia’s steel manufacturing sector doesn’t even rank in the world’s top 10, it is nevertheless the world’s largest exporter of iron ores.

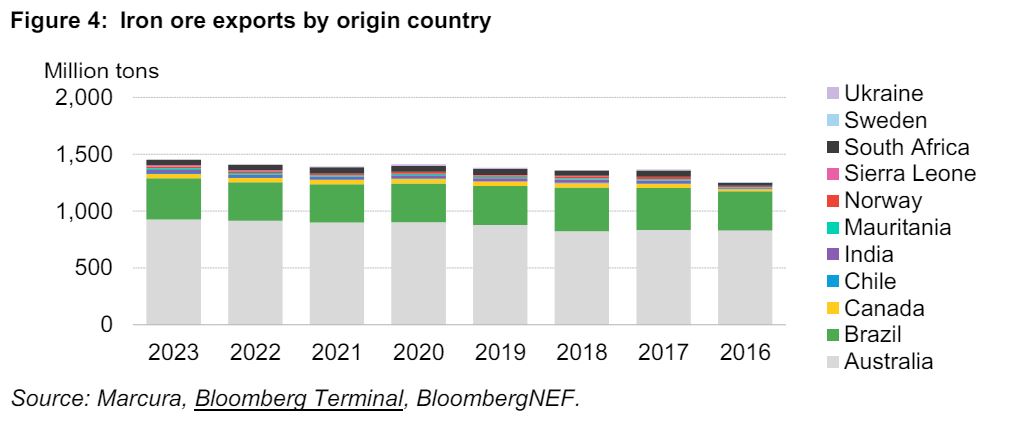

“In 2023, Australia supplied 64% of total seaborne iron ore,” writes Caroline Chua, BloombergNEF energy transition supply chain specialist and lead author of the report.

“Brazil is a distant second, accounting for 25% of traded iron ore in the same year. As the global steel supply chain transitions, Australia will have to transition to stay relevant in the sector, avoid stranded assets, and capture emerging opportunities for its export industries.”

But exactly how to achieve this and what technological pathway will be most cost effective and efficient is unclear. This creates opportunities, and risks, for Australian iron ore mining companies, who must act quickly.

For example, while unlikely to become a major steel manufacturer despite its rich iron ore deposits, Australia could nevertheless begin to export low-carbon intermediary iron products, ensuring its relevancy in the supply chain even as the sector decarbonises.

This could include transitioning to exporting low-carbon intermediary feedstocks such as green hot briquetted iron to export as a feedstock to overseas steelmakers.

BNEF predicts that Australia could utilise its current natural gas reserves, before transitioning to lower carbon fuels such as green hydrogen, to produce these emissions-abated green iron feedstocks for export – thus reducing the amount of abatement steelmakers need to achieve in the actual steelmaking process.

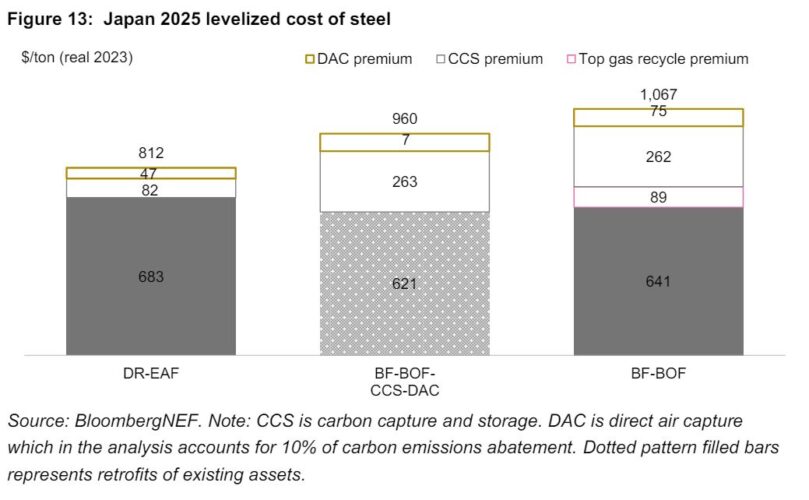

According to BNEF, Japan – one of Australia’s major iron ore trading partners – could choose to retrofit its existing blast furnaces which are paired with basic oxygen furnace plants (BF-BOF) with top-gas recycling, carbon capture, and storage (CCS), and introduce direct air capture (DAC) to capture CO2 directly from the air instead of point sources.

However, were Japan to introduce these three technologies (top gas, CCS, DAC), it would increase the levelized cost of steel by at least 51 per cent in 2030 – a drastic increase in cost.

The report concludes, then, that importing green intermediary iron products from Australia as a feedstock for steel production would be a more economical option for Japan as compared to importing iron ore and green hydrogen for its own decarbonised steel manufacturing.

Were Japan to seek to import both unabated iron ore feedstocks as well as green hydrogen from Australia – including the increase in complexity, cost, and inefficiency that is inherent in shipping hydrogen – in an effort to retain as much of the supply chain as possible, BNEF sees Japan losing out to countries with more affordable and available clean power and green hydrogen.

This demonstrates the opportunities open to Australian miners to decarbonise iron ore products for export while taking advantage of Australia’s existing green hydrogen ambitions.

“As the world moves to a low carbon future Australian miners will have to adapt or face major disruptions in their iron ore exports,” said Caroline Chua, BloombergNEF energy transition supply chain specialist.

“The steelmakers in countries like Japan and South Korea could have some success in using carbon capture and storage technologies to produce low-carbon steel. But these systems may prove challenging to install, difficult to scale, and expensive if they have to export captured carbon offshore for storage.

“Australia has the potential to produce and export cost-competitive low-carbon iron products to aid steelmakers in achieving their climate targets.

“Clean iron production could be a source of hydrogen demand, supporting Australia’s dream of being a hydrogen superpower.

“Australia is not alone and will face competition in the higher-grade iron ore and green iron markets despite its rich endowment of resources. Policy, trade, and technology partnerships will be critical for Australia to secure its place in the global race towards green iron and low-carbon steel.”