The rapid growth of wind and solar in Australia and the rest of the world is leading a major structural shift in power sector emissions that point to a significant decline in carbon pollution in come years.

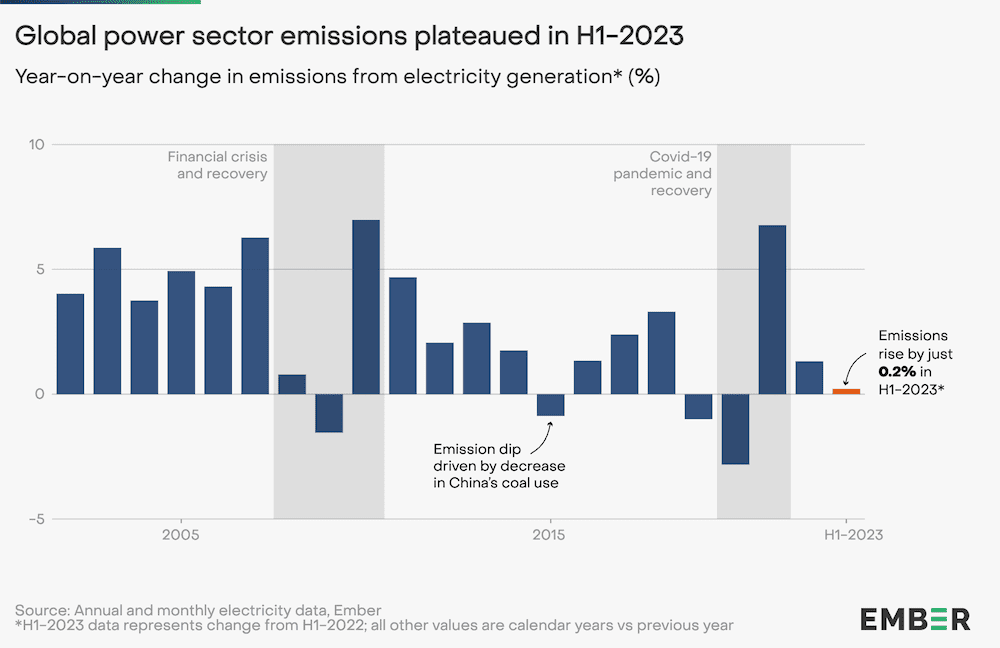

A new report by think tank Ember shows the global power sector saw emissions tick up by just 0.2 per cent in the first half of 2023, compared with the same period last year.

Emissions would have fallen significantly, however, were it not for droughts in China that had a major impact on hydro generation.

The report suggests 2023 might be the first year of structural power sector emissions reductions, if the growth in renewables continues, as this is the first year when emissions should have fallen, without a “shock” driver like COVID-19, given the amount of renewables available.

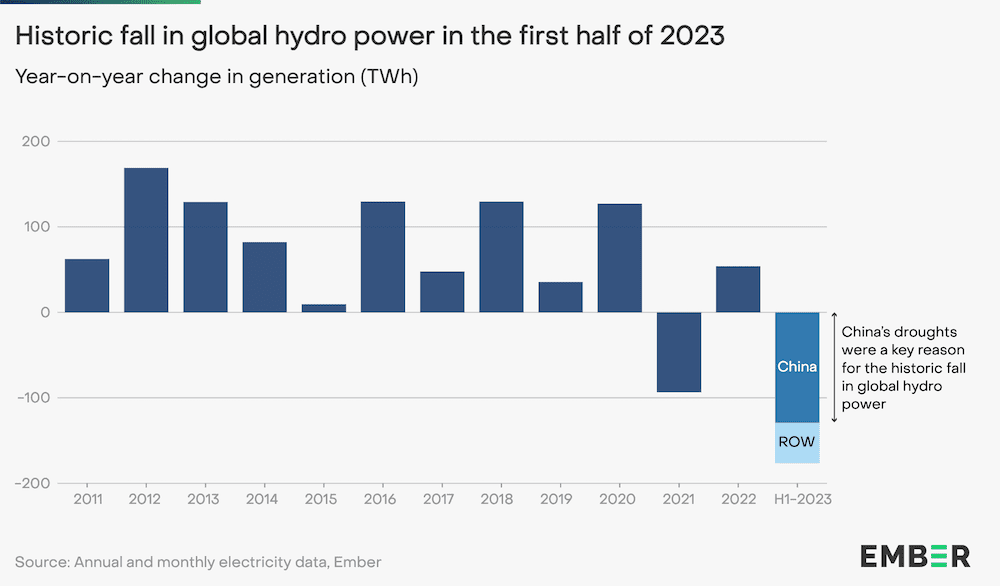

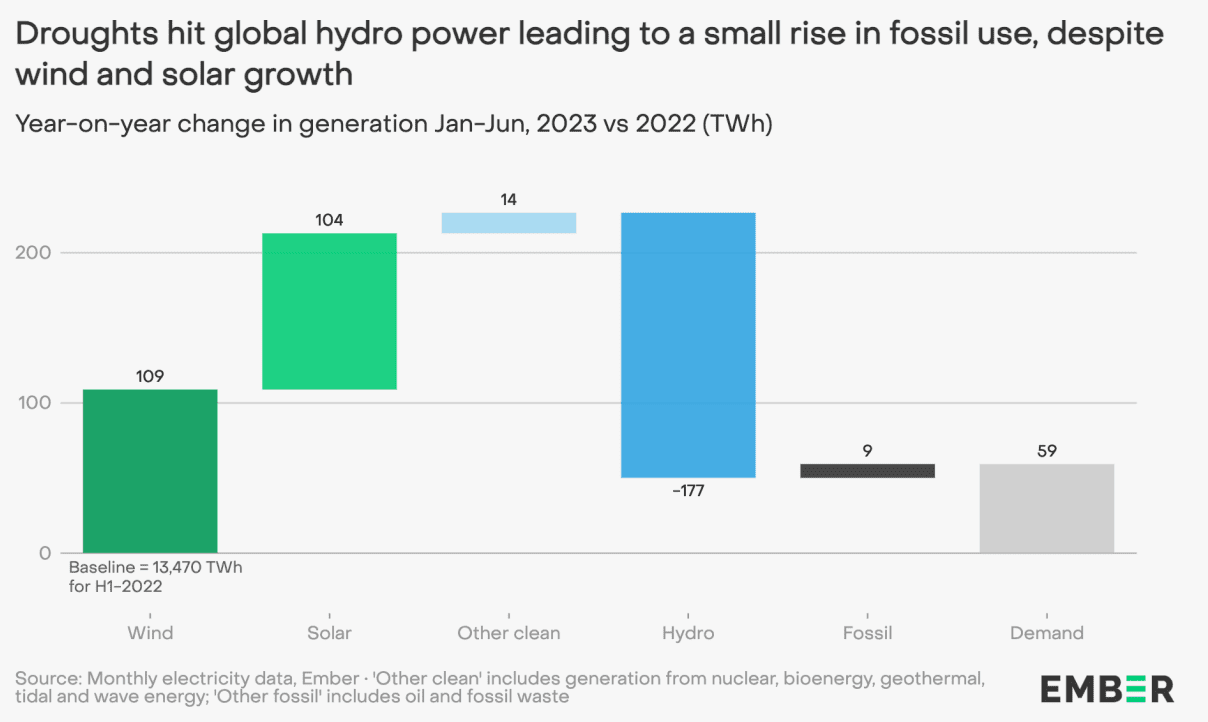

Although the world is seeing a rapid adoption of wind and solar, this was countered by falling hydro, as drought in China accounted for 75 per cent of a historic crash in global hydro generation of 177 TWh.

Power sector emissions would have fallen by 2.9 per cent, had global hydro generation been at the same level as last year – but even this picture is complicated.

Somewhat offsetting the rise of fossil fuels to fill the hydro deficit was low power demand, as the EU’s energy intensive industries were yet to recover from 2022’s high energy price-induced slump, and other advanced economies also experienced sharp declines in electricity use, according to the International Energy Agency.

Yet even as China was supporting its flailing hydro sector with coal and gas, that low demand globally cut into that fossil fuel generation and ameliorated some of the emissions which would otherwise have been created.

The Ember report found global electricity demand rose only 0.4 per cent in the first half of 2023, which is much lower than the 10-year historic average of 2.6 per cent.

Fossil fuels still a force to be reckoned with

The report did not include specific data for Australia. But the quarterly update of Australia’s National Greenhouse Gas Inventory, released in August, shows emissions trending slightly lower in the March and June quarters almost entirely thanks to energy sector reductions.

Ongoing reductions in emissions from electricity were down 3.9 per cent, or 6.3 Mt CO2-e, for the year to March.

In Australia, the numbers were put down to the growth in wind and solar, and particularly rooftop solar.

Around the world, the momentum of fossil fuels is still a force to be reckoned with.

“It’s still hanging in the balance if 2023 will see a fall in power sector emissions,” said Malgorzata Wiatros-Motyka, the lead author of the report and senior electricity analyst at Ember.

“While it is encouraging to see the remarkable growth of wind and solar energy, we can’t ignore the stark reality of adverse hydro conditions intensified by climate change.

“The world is teetering at the peak of power sector emissions, and we now need to unleash the momentum for a rapid decline in fossil fuels by securing a global agreement to triple renewables capacity this decade.”

Wind and solar on a tear

Ember’s global data is from January to June 2023 and covers 78 countries.

Wind and solar were the only two electricity sources that significantly increased their share of global electricity, together providing 14.3 per cent of global electricity in the first half of 2023, compared to 12.8 per cent in the same period last year.

But the amount of wind and solar added was less than in the same period last year, pointing to a slow down in investment in the sector as the consequences of higher costs and tighter supply chains continue to flow through the sector.

Solar in particular is growing quickly, given it can be installed much more quickly and easily than wind turbines, allowing 50 countries to set new monthly records for solar generation in the first half of 2023.

China accounted for 43 per cent of global growth in solar generation, while the EU, US and India accounted for about 12 per cent each.

Droughts may be the new normal for hydro

The droughts in China meant fossil fuel generators needed to fill the deficit created by under-performing hydro power stations.

Research indicates this could be the new normal for hydro power in southern China.

Climate change is causing the tropics to narrow, creating more and more powerful rainfall in that region, while the dry edges expand.

What this likely means for Asia is more rain over northern Australia – and less over southern China, researchers from the Center for Monsoon System Research at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing suggested in 2017, particularly during El Nino phenomena.