A major new Australian report has revealed that battery costs have fallen the most over the past 12 months of any generation or storage technology and will likely to continue to fall – given the right renewable energy policy settings.

The GenCost 2020-21 report, a joint effort of Australia’s premier science agency CSIRO and the Australian Energy Market Operator, delivers the latest annual update on electricity generation and storage costs, including projected future costs in line with changing global scenarios.

The 85-page report confirms that solar and wind continue – and will continue to continue – to be the cheapest sources of new-build electricity, even when the additional and not insignificant costs of supporting technologies like transmission infrastructure and storage are factored in to the bargain.

“We calculated the additional costs of variable renewable generation in 2030 is estimated at between $6 to $19/MWh depending on the VRE share (between 50% and 90%) and region of the NEM,” the report says.

“From 2030, when the new estimates on additional costs associated with increasing variable renewable generation confirms that they are also competitive when transmission, synchronous condenser and storage costs are included.”

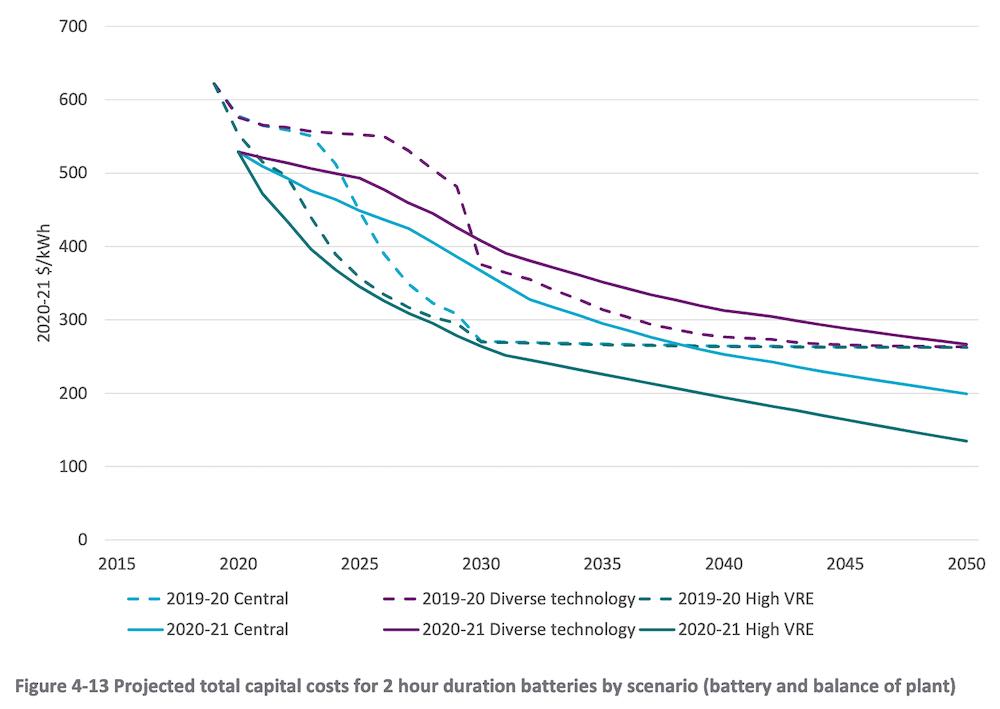

This is partly due to the falling costs of battery storage, which are noted as a standout feature of the 2020-21 period. As the report’s authors point out, this is important, because “falling battery storage costs underpin the long-term competitiveness of variable renewables.”

But it also works in the other direction, with scenarios of higher uptake of variable renewables in turn accelerating the learning rate for batteries (table 3-3).

Further, the report shows that when batteries are integrated with existing power plant – and can share some of the power conversion technology – this results in a 9% lower battery cost (for 1-hour duration), scaling down to a 2.5% cost reduction for 8 hours duration.

Like other reports before it, the GenCost 2020-21 report confirms that under what it calls a High VRE scenario – “a world that is driving towards net zero emissions by 2050 and where technical, social and political support for variable renewable electricity generation is high” – future generation costs would be the cheapest.

This is particularly the case for battery storage, as is illustrated in the chart above.

“Battery deployment is strongest in the High VRE scenario reflecting stronger deployment of variable renewables increasing electricity sector storage requirements and stronger uptake of electric vehicles to support achieving near zero emission by 2050,” the report says.

“Together with an assumed high learning rate this leads to the fastest cost reduction which is most consistent with recent trends.”

Unfortunately for Australia, current federal government policies appear to place it in what the report describes as the Diverse Technology scenario, which places Australia about 20 years behind most developed countries which are committed to net-zero emissions by 2050.

“Furthermore,” the report adds that under this scenario “there is lack of social, technical and political support for variable renewable electricity generation and subsequently a greater role for other technologies.”

That is, with less support for a rapid and ambitious rollout of wind and solar, the grid share of non-variable renewables languishes at around 60% and generation from gas and coal with carbon capture and storage is deployed to meet 2050 climate policy targets. CCS is also used more commonly in hydrogen production.

Gas, the Morrison government’s favourite “low-emissions” technology comes the closest in cost to VRE, according to the report, but only on the assumption that a combined cycle generator is able to match the costs of variable renewables with integration costs at a 70% or greater share.

But – and there are about three very big “buts” when it comes to cost of gas – the report stresses that “the low range 2030 gas combined cycle cost assumptions require investors to assume no climate policy risk at the financing stage (despite the 25 year design life extending beyond the net zero emission targets of most states).

It also requires a gas price just below $6/GJ throughout that period and a capacity factor of 80% in a system with 70% or greater share of energy from near zero marginal cost renewables.

Of course, none of those are likely to happen. The gas price is likely to be higher, and the sort of gas projects proposed by the likes of energy minister Angus Taylor at Kurri Kurri assume a capacity factor of just 2 per cent. Which means they will be charging like a wounded bull before being switched on.

Equally as unlikely, nuclear of the small modular reactor variety is flagged as also playing a potential role in the Diverse Technology scenario from 2030, presuming investors were willing to drive down costs through multiple deployments elsewhere in the world in the late 2020s. Goodness knows, Grant King is working on it.