US oil and gas giant ExxonMobil announced on Wednesday the long-anticipated closure of its Altona oil refinery, long thought to be uneconomic but hit directly by the Covid-19 pandemic and the resultant drop in oil demand across the world.

The news comes after a major ‘rescue package’ for oil refineries was announced in December last year. “Minister for Energy and Emissions Reduction Angus Taylor said the government was taking immediate and decisive action to keep our domestic refineries operating”, said a government press release last year. “The production payments will help the industry withstand the economic shock of this crisis, protecting local jobs and industry, bolstering our fuel security and shielding motorists from higher prices.”

The scheme was meant to offer a minimum one cent payment for each litre of primary transport fuel from major domestic refineries that stay open in Australia; however the owner, ExxonMobil, opted not to take up the offer. The only one of four refineries to take up the offer was the Viva refinery, reported the Australian Financial Review.

Exxon: 2020 loss of $22.4bn

Shell: 2020 loss of $19.9bn

Total: 2020 loss of $7.2bn

BP: 2020 loss of $5.7bn— Merve Erdil (@merveerdill) February 9, 2021

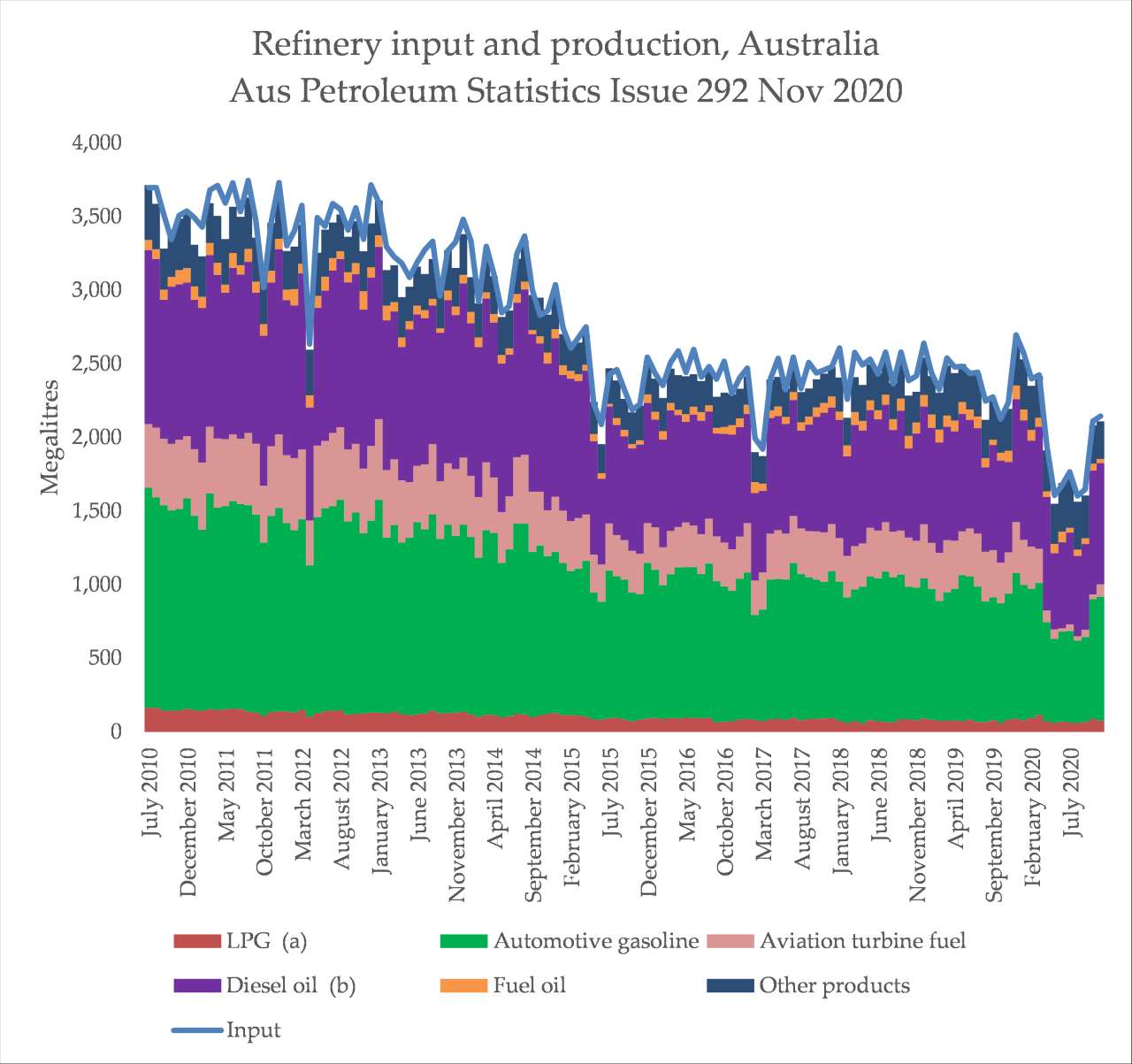

Australia’s refineries have been undergoing a structural decline over many years, for a variety of reasons. British fossil fuel major BP closed its oil refinery in Kwinana, in Western Australia, in October last year. Fossil fuel majors have not generally seen the bulk of their revenues flowing from oil refineries in Australia, the currency has been high, and COVID19 has delivered a shock to the system that has accelerated the long term trend, as shown in Australia’s Petroleum Statistics.

A December 2020 Parliamentary Library post by Dr Hunter Laidlaw examines the consequences for this declining refinery output for Australia’s fuel security. “As refineries close, domestic refining capacity and capability reduces and Australia becomes yet more dependent on imports of refined product. Australia’s fuel supply therefore becomes more reliant on industry’s ability to source and ship the necessary fuels when required,” he wrote. “Once closed, refinery sites are often converted into fuel import and storage terminals (as announced for Kwinana), so remain important facilities in the fuel supply chain. However, having fewer refineries reduces Australia’s ability to refine fuels if shipping and supply chains are ever severely disrupted for any reason in the future.”

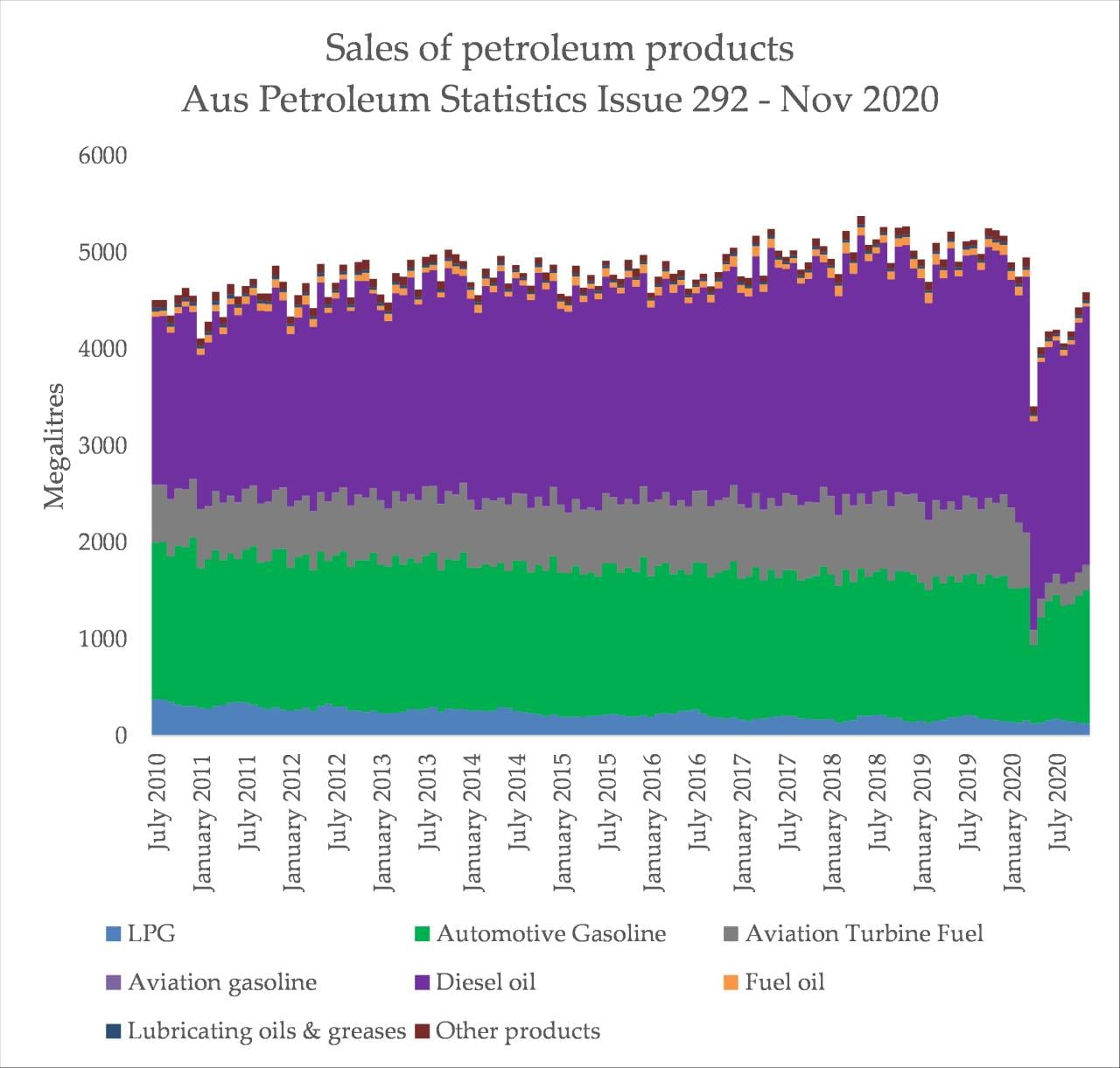

Despite falling refinery output, the long-term trend for Australia has been increasing consumption of petroleum fuels, due to a rising population and near zero change in the modes of transport available to Australians.

This, paired with the decline of refineries, has meant that the quantity of crude oil imported has decreased, while the quantity of already-refined products has increased. Australia produces very little of its own oil; relying mostly on imports (mostly from Asia for refined products, and Malaysia, the US and the UAE for crude oil).

The Australian government has been working to increase its “stockholding” of fossil fuels, in response to this increased reliance on a variety of complex global shipping and supply chains for Australian transport.

When BP announced the closure of its Kwinana oil refinery, several experts and commentators highlighted the problem of fuel security could be eased immediately through strong incentives to electrify transport in Australia. Ben Cerini, a consultant at Cornwall Insight, said “A strong policy position to incentivize the uptake of EVs is needed. The benefits will ripple through all aspects of the Australian economy.”

Though the closure of the Altona plant was anticipated, it comes only days after Australia’s Energy and Emissions Reductions Minister Angus Taylor announced a plan to not reduce emissions in Australia’s transport sector, with a discussion paper avoiding any new policies that would lead to significant departure from the projected future of land, sea and air transport in Australia. The plan was heavily criticised by experts and advocates for being a ‘do nothing’ policy; in stark contrast to the flurry of interventions Taylor has announced to subsidise the import, storage and refining of fossil fuels for transport in Australia.

Taylor’s plan focused heavily on hybrids – “mild” hybrids, not plug-in hybrids – to reduce emissions in Australia’s transport sector, despite that technology still relying fully on imported fossil fuels. The report’s analysis ignored falling emissions in the grid to each faulty conclusions about pathways for decarbonisation. A wide range of countries have engaged in either aggressive incentives for electric vehicles or phase-out dates for fossil car sales, or both. Australia is set to face increasing pressure during the year as the 26th Conference of Parties meeting looms closer, but these shifts in domestic fossil fuel industries will create pressure at home, too.