After being delayed for just under two years, chances are that Australia’s government is due to release its road vehicle transport strategy, probably under the headline of a “future fuel” strategy (instead of a “National Electric Vehicle Strategy“), likely paired with the release of its upcoming emissions projections report.

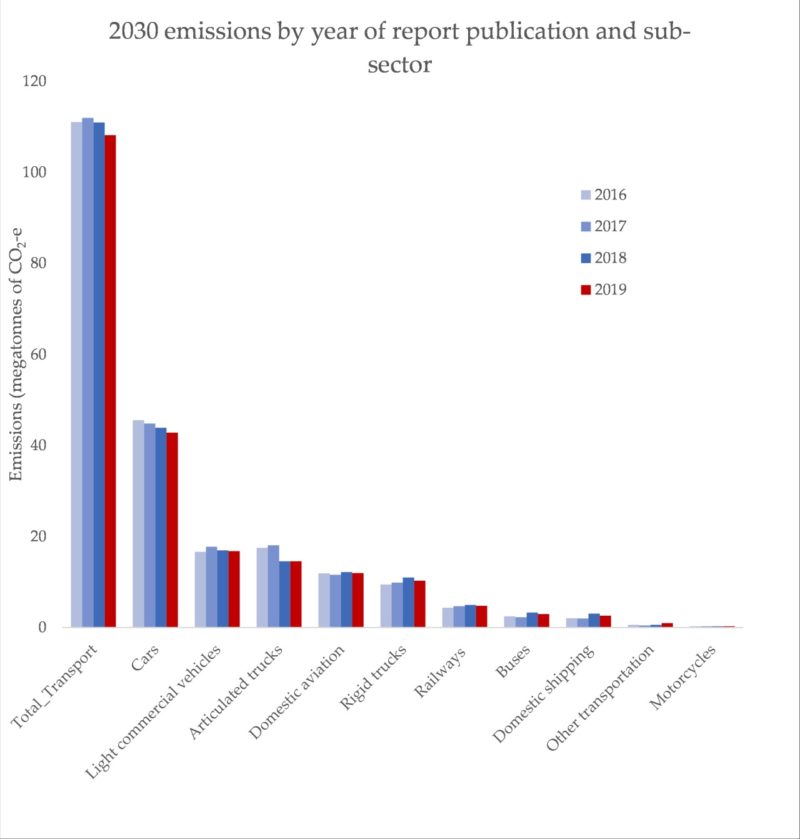

In previous versions of Australia’s emissions projections, the transport sector has barely shifted between different version of the report released each year. There has been a decrease, but it has been so small that total transport emissions are still projected to increase:

Drilling down into a sub-section of transport, much of that small decrease comes from cars. 2030 emissions from cars were predicted to be 46 MTCO2-e, in the 2016 report. The 2019 report reduces that to 43. It’s tiny, but it’s still the biggest change of the lot. “This projection shows a stabilisation of emissions, especially from road transport, despite a growing economy, population and transport activity. The cause of this shift is improvements in engine efficiency and the emergence of electric vehicles”, wrote the Department, in their 2019 report.

In that report, electric vehicles and plug-in hybrids comprise 19% of total new vehicle sales in the year 2030, which translates into 6% of the total light vehicle stock in Australia.

As I wrote at Renew Economy, the upcoming 2020 projections will be an excellent empirical baseline to test the actual predicted changes that come about as a result of new government policies. To be aligned to the core goals of the Paris Climate Agreement, analysis firm Climate Action Tracker estimates far more than tiny, barely-noticeable changes need to happen in Australia’s transport sector, in their country profile for Australia.

“The CAT Paris Agreement-aligned benchmark requires Australia to increase its share of electric vehicles (or other emissions-free vehicles) in new vehicle sales from less than 1% today for personal cars, light duty vehicles and buses to 95% in 2030 to reach 100% in 2035. This would translate into about a 38% EV share in the total fleet of cars and buses on the road in 2030 and, combined with the decarbonisation of the power sector, would result in full decarbonisation of this fleet by the middle of the century”.

In the report, a 1.5C scenario sees Australia’s transport emissions hit around 60 MT by 2030 – just under half of what the 2019 projections report predicts. So will the Morrison government’s new transport policy do what needs to be done? Will that gap between the red 2019 prediction and what’s needed for climate ambition be filled?

No, it definitely won’t

It’s worth pausing to hear a reminder of the Morrison government’s comments on electric vehicles made around the 2019 federal election, as featured on a recent episode of Guardian Australia’s Full Story podcast, with their environment reporter Adam Morton. At an April 2019 press conference in the Central Coast, Business Minister Michaelia Cash said“But what I worry about for people like Johnny is that the car he’s driving today, if a Labor government is ever elected, will not be the car he is driving tomorrow. In fact, if you look behind us at all of these apprentices here, 50 per cent of those apprentices will be driving an electric vehicle under Bill Shorten”.

Around the same time, PM Scott Morrison said of electric vehicles: “I’ll tell you what; it’s not going to tow your trailer. It’s not going to tow your boat. It’s not going to get you out to your favourite camping spot with your family. Bill Shorten wants to end the weekend, when it comes to his policy on electric vehicles, where you’ve got Australians who love being out there in their four wheel drives. He wants to say ‘see ya later’ to the SUV when it comes to the choices of Australians”.

Key members of the Morrison government are keenly attuned to the commercial allure of electric vehicles. This is a very long thread featuring several of them posing with EVs in photo opportunities, each well prior to the flurry of attacks that preceded the election.

. @JoshFrydenberg likens electric cars impact in transport sector to iPhone in communications, says those ridiculing them will end up buying them

— Kieran Gilbert (@Kieran_Gilbert) January 22, 2018

Morrison is extremely unlikely to adopt a heavily interventionist approach to electric vehicles. They presented intense opposition to Labor’s 50% renewable energy target as a key message in their election campaign, and were deeply embarassed to discover that that’s the default future for Australia’s grid. They also presented intense opposition to Labor’s 50% EV-sales target (that’s of new cars bought, not of the fleet of cars in total) as a key message.

What the policy will probably look like, and how it will be sold

Morrison’s electric vehicle policy will incentivise some of the enabling infrastrucuture for an EV transition, including incentives for new charging stations, research into vehicle-to-grid charging and ARENA-funded research projects. It will probably pin hopes on biofuels, engine efficiency and developments in battery storage. There will be some flashy funding for hydrogen. It will focus on those sectors I showed above that are smallest: heavy vehicles, road freight and domestic shipping. The only actual incentives will be for big business fleets, rather than for consumers (who are the bulk of car owners).

It will be the “technology roadmap”, but purely for transport. A job advertisement appeared about a month ago for a “federal government client” focusing on the development of this “future fuels strategy”.

The plan will always be to never, ever intervene. “Technology not taxes” has been the mantra for a year now, and it’ll be repeated ad-nauseum at the press conference for this. The goal, as always, is to present a policy that sounds vaguely like its doing something, but is doing nowhere near enough what’s needed to reduce emissions as fast a possible, while maximising the benefits of that transition to Australians. It’ll sound technological, flashy and liberal-minded.

It’ll present a false narrative about letting Australians “have a choice” about whether they buy a new EV or not, in contrast to Bill Shorten’s Iron Electric Fist. The “technology roadmap” signposts this focus on “choice”: “The Strategy will look to enable all technology choices, including hybrid vehicles, fuel cell electric vehicles and battery electric vehicles so Australians can choose to adopt new new vehicle technologies, where it makes sense for them to do so”. And Taylor told CarAdvice recently that “Australians should be able to choose which type of car they drive and the Morrison Government will support them in this decision”.

It’s nonsense, of course. Policies to accelerate the transition to electric vehicles don’t remove choice – they address the structural barriers that actually prevent choice, because combustion engine cars have the inherent, unfair subsidy of causing harm to health through carbon emissions, air pollution and noise without paying for that impact.

We know that a fast, forced transition to EVs is beneficial – reductions in air pollution and noise alone are significant, before we even take into account climate change. We also know that it simply won’t happen without intervention. BloombergNEF’s Akshat Rathi writes that “without the ban or other incentives, EVs would make up 42% of U.K.’s new car market in 2030 and 56% in 2035. Cars in the U.K. typically last 14 years, according to Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders, and thus simply relying on market forces would mean the country blows past its climate goal. It’s also why 13 other countries have set similar targets, with Norway’s ban on new fossil fuel cars coming as soon as 2025”.

Using tweaks to tax systems and incentives, such as Norway’s tax exemptions, waves parking and ferry fees, access to bus lanes and free or dedicated parking results in a consequent change in the distribution of car sales. No one’s forced to do anything: tax simply ensures the massive climate and health impacts of combustion cars are priced properly. It is exactly what must be done to create massive, fast and beneficial change in the stock of Australia’s fossil-fuelled fleet, and it is exactly what the Morrison government will not do.

See also: 2020 was the starter pistol on EVs – now the world looks to Norway for inspiration