For nearly 30 years the electricity market in Australia has operated with few significant problems, and certainly none that would call for a suspension of activities.

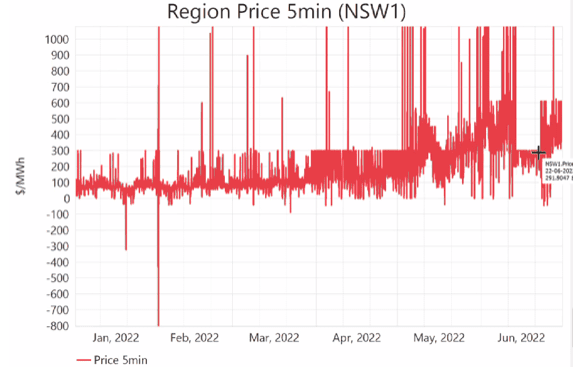

But on Tuesday, June 14 this year, the market and system operator (AEMO) decided it had to take urgent action. As the cost of running generators climbed higher and above a threshold price, the various generating companies that compete to provide electricity had started to opt-out. They could no longer afford to generate at the prices being paid.

The breakdown in generator supply economics didn’t mean the lights went out, because there was an emergency provision for just that situation. However, during the period the market was suspended, the competition mechanism was replaced by a direct payment to the generators, in order to compensate for operating at what was a significant loss.

Now, three months later, the NEM has returned to normal operation, albeit with much higher prices reflecting the continuing high prices of coal and gas. But the event has sparked a strong perception that maybe something seems broken in the system and that something should be done.

The stakes seemed high enough: We had Australia’s energy minister urging households in New South Wales to switch off their lights to help ease the shortage.

Elsewhere there were consumers and industrial players that were, and still are, feeling the pain. South Australian manufacturer InterCast and Forge, a big user of electricity, was forced to turn off their plant and stand down staff.

The ingredients were there

Yet perhaps the most striking of all in this scenario is how the cards have been on the table for a little while. With rising gas prices, retiring coal plants and others that are out of commission, the ingredients were there for all to see.

However, none of the three main bodies controlling this, the combined market and system operator AEMO, the market commission AEMC and the regulator AER, collectively called the Energy Security Board (ESB), ever saw this coming, judging from the narrative of the Post 2025 Project.

Below: Medium Term Projected Assessment of System Adequacy (MTPASA) showing a drop in available capacity prior to the NEM suspension, as demand climbs.

That in itself is something of a mystery, and to some extent points to an inward-looking nature of the system that controls our electricity.

It has certainly created the notion in the electrical community that something should be changed. There were a slew of directives coming from the AEMO with a volume that could not be considered normal.

Is it a crisis?

But what should really be changed when the system didn’t actually ever do something that wasn’t part of the system design?

Certainly what was instrumental in going into emergency provision was the Cumulative Price Threshold (CPT). This is effectively a cap on the cost to retailers, established by time averaging the price; or in more mathematical terms, taking the area under the price curve when plotted against time, which reduces the impact of the short price peaks in the situation.

It was the way peaks were tamed, before calculation of the generator’s revenue package, that led to a situation where the generators didn’t want to play during a peak, and then opted for the administered price route to come into force instead.

This could all be changed, but then, it’s important in limiting the risks for retailers. You could increase the CPT, but then retailers would have a higher risk meeting additional hedging costs and higher costs to consumers. So there’s a win-lose if that route were chosen.

Other proposed changes are to introduce a (reserve) capacity market. This could be a quick-fix solution to address the rapidly dwindling fossil-driven asset generation that leads to unacceptable deficits in meeting system security and reliability.

This would be effectively a supplementary market of generators paid to be ready to go at short notice, if there’s nobody else willing to do so, as happened in June. The price implications of this are clear when you examine how it would work.

If you think about the analogy of a city paying a certain number of Airbnb lodgings to stay unoccupied every month, so tourists never run out of places to stay, you lower the prices other hotels can charge because no one is ever going to be out in the cold. But you also have to distribute the cost of the spare empty rooms you are paying for. This means the market is less peaky but generally higher, which may suit some. Several countries have adopted capacity markets after extensive price comparisons.

But the criticism levelled at introducing a capacity market is precisely this: Not only do you have higher average costs, but the peak is also a valuable signal that indicates potential profits for battery systems.

It’s the peak that encourages investors in utility battery systems to enter the market. From that point of view, a capacity market might be a bad idea because it discourages the very type of renewable fix that is required.

On the other hand any capacity market would almost certainly be designed to encourage battery systems to enter the system, so maybe a capacity market wouldn’t have a negative impact at all.

Certainly, the installation of a capacity market has been a controversial topic and experts are somewhat divided as to the best way to go. One thing most agree on is that a capacity market represents a step towards centralisation, and that could be seen as a retrograde step. But it does not need to be. There are many other things you could change, if change is what you want.

Andrew Campbell, a director at Marsden Jacobs consulting, points out that there are three levers to consider.

There’s the design of the market and the rules that reflect the design, there are the settings (like the Market Price Cap which are reviewed periodically), and there are policies which influence outcomes (such as renewable generation targets). All of these influence future outcomes and are relevant to assessments of potential market changes.

One possible shift that needs to occur is the de-emphasis of utility-level solutions and more attention focused on the smaller scale components. While the utility level solutions have been getting themselves in knots, much progress has been made at the other end of the electricity generation spectrum.

LEMs as a solution

For a little while now, the industry has shown a growing awareness of the problems described above, though in a state you could characterise as partial denial.

Against this background, some new schemes have been tried which explore the notion of locality and also temporality in pricing. In other words, pricing that is sensitive to the precise demands of any particular time and place, which you might term spatio-temporal pricing

For example, the US has used nodal pricing whereby prices are created for the transmission system based on local shortages or surpluses at the various nodes, the places where power comes in and out of the grid.

This appears to have been successful in dealing with grid congestion, a long standing problem as solar and wind have become more prevalent. But nodal pricing brings an element of basis risk and overheads too. There are also doubts as to whether it really does improve the development of the transmission network.

Such spatio-temporal prices like Local Value Pricing and Local Marginal Pricing, especially on the distribution level, are localised approaches that aim to reduce the centrality of the pricing, one of the drivers for the system breaking down.

Australia is far off from implementing them. There is talk of these being tried by AEMO in their transmission network by the year 2025, and while they have made things better there is a growing sense that a more radical re-conception of the entire system is needed.

A complete rethink

One of the most innovative suggestions that some members of the electrical community have advanced is called a LEM, or Local Electricity Market. This involves a complete re-think and indeed a reversal of everything of the old system.

A LEM is basically a nodal market that involves say, for example, one household with batteries storing another household’s excess solar, and then dispatching it back to that household later in the evening. Although the basic paradigm was created for domestic players, the concept scales up to involve grid players and indeed the whole grid.

Where the old system was centralised, this new system is hybrid decentralised. Where the old one was predicated on maintaining a steady price to the end consumer, this one allows infinite variations dependent on time and place. Where the old system depended on a slab output of electricity called baseload generation, the LEM system will thrive on a variable one.

And where the old systems use curtailment or penalties for overproduction, LEMs are more carrot and less stick. They also integrate demand-side management, the orchestration of big electricity users like aluminium smelting so they cut their demands and help to balance the grid.

This can all be done in a LEM style scheme. So it really is very different, hence the nervousness and apprehension surrounding it.

The changing nature of the NEM, and changing costs to consumers, will mean the returns from LEM will probably increase by a significant amount.

Ironically, LEM is a solution that, of all the proposed approaches, would be the one that could be implemented the fastest, because the generation is there.

Perhaps for these reasons, the LEM approach is being tested in several different locations and is gradually emerging from its place as a theoretical object of interest, by university PhDs and electricity boffins, to becoming a more mainstream topic of conversation for electrical utilities.

The grid benefits of LEMs

LEMs suit solar and wind outputs much more than centralised electricity systems do, because the agility of a LEM market matches the variability of decentralised solar and wind outputs, especially if increasing amounts of battery storage come onto the system.

LEMS also provide the kind of agile price signals that encourage investment in battery systems which benefit the grid at large. For these reasons, they may offer a solution to the market breakdown we are seeing in Australia today.

Moreover, a LEM can work alongside any form of capacity market so they can work in tandem with other options. This means retailers who encourage the use of participants’ batteries can reduce their RRO obligations.

They also can be structured to facilitate the production of other vital attributes; Synthetic inertia, which is the part solar and wind will need to produce so they can offer what fossil and old fashioned generators used to produce for free, can also be provided if you have a big enough battery system with the correct inverter and controller technology.

In industry parlance, battery systems can also provide FFR – fast frequency response. The Walgrove battery of 50MW is being tested to see frequency deviation arrest in less than a second.

This will be part of the new world of synthetic inertia, essentially the attributes of big old fashioned flywheels, but synthesised via batteries and smart semiconductor technology.

But if households are persuaded to invest in their own battery capacity because they’re part of a LEM, investment in big battery schemes like Walgrove can theoretically be deferred. And so while a LEM does not replace a utility market, it can do a lot to supplement it.

It can certainly provide the potential for a significant level of controllable supply through storage and demand management trading within and across other local electricity markets. It could also help the economic balance between DER and utility scale assets.

But the LEM concept is very new and many electricity experts don’t yet know much about it. The ones that do are intrigued, but say they need to see more data to get a better idea of how LEMs perform.

Even if the conflict in Ukraine subsides and some of the pressures on costs reduce, there is still a need to change.

Australia is home to many ageing fossil plants with their problematic and failing boilers that are due to be retired in the next few years.

You might think that we could always go back to where we used to be and fund some more coal-fired power plants; that we could simply replace the rickety ageing ones that are now coming to the end of their useful life, and thus make the problem go away. But the world has moved on since then and that option is not on the table any more.

The reason for this is that you’d be hard-pressed to find any bank that wants to fund a new coal-fired power plant. Politics and technological leaps are cutting the service life of such generators to being uneconomically short, which means the interest payments would be unfeasibly high.

A rock and a hard place

In some ways, the AEMO, the AEMC and the regulator, AER, are caught between a rock and a hard place.

Any attempt at a patchwork fix of the situation will lead sooner or later to more government-funded bailouts, few want to see and will certainly result in a death spiral for any market. So a patchwork fix is an unlikely outcome, but are the AE trio on the right track?

The new paradigm of Local Energy Market, which the trio has been very slow to comprehend, could offer a long-term solution. But even in hybrid form, will it bring wholesale disruption?

Whatever they decide, the stakes are undeniably high. The rocketing prices could drive InterForge and other big electricity users out of the country, which would be a blow for the economy. Also, the volatility of the market has seen off many retailers and there are predictions that half may go out of business by the end of 2022.

In the new LEM model, retailers could maintain their margins and, in fact, those retailers who have customers that have a lot of solar and battery could, if they get the right weather, even make an increased margin. But that is a big “if”. Also, fully functional LEMs will also reduce prudential requirements for electricity retailers.

On the downside, a LEM does require managing a more complex portfolio of prices over time and place, so not all will be geared up for this. But the technology is there to make this kind of data-intensive approach relatively easy.

When energy and economics collide

Perhaps what the concept of an LEM also points to, is a deeper issue of the present lack of understanding and attention to the boundary line between economics and energy.

We have economists who tend to exclude energy as part of their understanding, and only a handful of people like the Chech-born Vaclav Smil who work in a dual capacity of both economist and energy.

It’s a point argued very well by Matthew Syed in the Sunday Times, The future will be cold and dark if we don’t have a radical rethink.

That need for that dual understanding is now everywhere, and not just in the refined corners of energy market design. We can no longer get away with a shoddy energy policy and hope no one notices, or that the can will be kickable someway down the road.

The LEM concept asks each and every one of us to start thinking about and owning the economics of energy, for our individual and communal benefit. Perhaps this crisis arrives not a moment too soon.

Dr Jemma Green is co-founder and chair of Powerledger, a tech company that uses blockchain for energy and environmental commodity trading.