Energy utilities are facing increased risks and costs as they attempt to manage their asset bases in a way that adds economic value (parenting advantage) as energy markets are disrupted and evolve into both distributed and centralised entities.

To date this analysis has focused more on the politics, customer and industry implications rather than what it means for utilities as they manage these risks, and what it will mean for their asset bases which are made up of centralised fossil fuel generators and renewables which bias towards distributed markets.

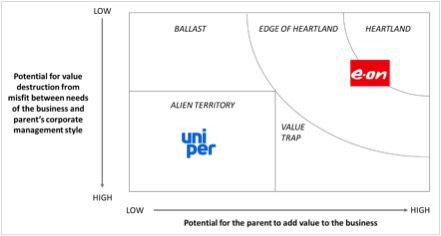

The motivation for this analysis came from the experience of EON in Europe (and RWE) who recently underwent a demerger (September 2016) because their centralised fossil fuel asset base (Uniper) and its now distributed customer focused renewables business (EON) could no longer be managed as part of a single corporate strategy.

What is Parenting Advantage?

For those of you unfamiliar with the dark arts of corporate finance, the concept of parenting advantage is essentially the additional value that a utility brings to the ownership of its assets as a result of its scale, its management competitive advantage and the diversification of its business units.

There are a number of conglomerate type companies (Australia’s Wesfarmers and US retail giant Walmart) that fit this mould, where they are able to extract greater shareholder value from their ownership of these assets than they would as stand-alone businesses or in the hands of their competitors.

Maximising shareholder value and parenting advantage are highly correlated regardless of industry but are becoming increasingly important concepts to manage for both energy retailers and utilities.

While all global energy markets are different and have their own regulatory nuances a good lesson on what can go wrong can be learned from EON, whose market capitalisation dropped from its peak of 90 billion Euros to just 16 billion Euros in September 2016.

They sought to deal with the upheaval in the regulatory positions, but it was the emergence of a highly innovative, technology driven, distributed energy market that ultimately broke the EON business model – forcing a demerger.

It is in this context that the lessons learned with regards to parenting advantage (asset management) in Europe can be applied as this disruptive change to energy markets is more acutely experienced globally. This is going to be especially important in markets such as Australia and North America, but will become more extreme in any grid globally with areas of high solar irradiance.

The Ashridge Model below highlights the potential for parenting advantage when trying to manage both the low growth centralised assets and the high growth distributed assets as part of a single corporate strategy.

As the cost of solar, storage and wind continue to fall and the forces magnifying this diverging market trend will continue to increase the pressure on the potential for parenting advantage at a utility level.

In addition to the problems of parenting advantage in a divergent energy market there are likely to be three key strategic areas EON would have struggled with prior to the demerger:

- Brand Management and Reputation – It is almost impossible to position as a clean, green energy provider to one customer segment whilst owning a fleet of carbon intensive thermal generators.

- Staff and Management expertise – the employee workforce skills required to run and manage a distribution network is quite distinct to the skill set of a software engineer managing a battery and demand management service for distributed energy.

- Prioritisation of capital and expertise allocation – where do you put your financial and human resources expertise – in your low growth declining carbon business or into your high growth renewables business? (a whole article coming on this tomorrow)

Managing shareholder value is a tricky business at the best of times but if you add to this list policy uncertainty and the cannibalising of one asset base by another you do have to spare a thought for the executives running these firms.

As these market forces now continue to accelerate globally it is going to require some very careful modelling to assess the relationship between the benefit of any synergies and the liability of asset cannibalisation over time.

If a utility has a competitive advantage relative to its peers in both the centralised and distributed markets it may make sense to accept the liability of asset cannibalisation if the synergies are great enough but this is more likely to be the exception rather than the rule.

What happens in other jurisdictions will be intriguing but in the case of EON the market agreed with management’s decision to demerge and added two billion Euros to the combined market capitalisation of the two companies.

By allowing them to tailor their corporate strategies to their respective markets and removing a lot of the internal conflicts they were able to unlock shareholder value by removing this parenting discount on the asset base.

Given the lack of corporate agility and illiquid nature of their assets it is highly likely that this destruction of shareholder value will be repeated in other markets globally especially if the market divergence happens quickly.

But if the lessons of European markets have taught us anything it is that if management allow their asset bases to trade at a discount under a single corporate strategy eventually shareholders will get their way.

Matthew Grantham is a guest contributor for RenewEconomy and a Radio Presenter at Beyond Zero Emissions,