The cost of solar and wind energy will continue their stunning falls over the next decade, and by 2027 will be cheaper than existing coal and gas plants in most countries in the world, according to a major new report by leading global analysts Bloomberg New Energy Finance.

In its annual New Energy Outlook, NEO2016, BNEF says solar energy costs, which have already fallen by 80 per cent since 2008, will fall another 60 per cent to an average cost of $40/MWh around the world by 2040. In some countries, that cost has already been beaten.

This “precipitous” fall, as BNEF describes it, means that solar will account for nearly half of all new capacity installed around the world in the coming decades. One third of this will be on rooftops, and it will be accompanied by huge growth in battery storage. By 2040, solar will supply 15 per cent of all electricity demand.

Wind energy costs will also fall another 40 per cent, mostly driven by improving capacity factors that will rise to 33 per cent in 2030 and 41 per cent in 2040. It will account for more than 20 per cent of all new additions.

Prices will remain low for coal and gas, because of falling demand, but wind and solar will still be cheaper than these fossil fuels by 2027 in most parts of the world. “This is a tipping point that results in rapid and widespread renewables development,” the BNEF report says.

That means that the role of coal and gas will change completely from the concept of “base load” to that of gap fillers.

“As natural gas and coal plants are increasingly idled in favor of renewables, their capacity factors will take a big hit, and lifetime cost of those plants goes up. Think of them as the expensive back-up power for cheap renewables.”

The signs of this have already started to emerge in Australia. In May, thanks to record amounts of wind generation, most wind farms operated at capacity factors of more than 50 per cent, more than many coal generators. And that is before the imminent deployment of huge amounts of large scale solar.

Indeed, Australia is cited as one of a few countries, also including Germany, Mexico and the UK, where wind and solar provide more than 50 per cent of demand (as it will already do in South Australia by the end of the year).

“With the increase in renewable generation comes a fall in the run-hours of coal and gas plants, contributing to the retirement of 819GW of coal and 691GW of gas worldwide over the next 25 years,” the report says.

“The fossil plant remaining on-line will increasingly be needed, along with new flexible capacity, to help meet peak demand, as well as to ramp up when solar comes offline in the evening.” This, of course, is already happening in South Australia.

Around 336GW of this ‘flexible capacity’ is added in the OECD, and 938GW globally, to 2040, BNEF says. Much of this comes from battery storage.

Small-scale battery storage, for instance, will become a $US250 billion market and the rise of EVs will drive down the cost of lithium-ion batteries, making them increasingly attractive to be deployed alongside residential and commercial solar systems.

“We expect total behind-the-meter energy storage to rise dramatically from around 400MWh (megawatt hours) in today to nearly 760GWh (gigawatt hours) in 2040.

EVs will make up 25 per cent of the global car fleet by 2040, providing 2,701TWh of additional electricity demand, to reach 8 per cent of world consumption.

In turn, cheaper batteries increasingly bring small-scale and grid-scale storage options into play. And that is further helped by the arrival of “socket parity” – where rooftop solar is cheaper than grid power for consumers. That already exists in Australia and many other countries but will world-wide

The report obviously has significant implications for Australia and for its current economic policy settings.

BNEF says the seaborne thermal coal trade – on which Australia relies for its coal exports – is already in structural decline and prices will not recover. It also says that there will be no “golden age” of gas because renewables and other flexible generation will be cheaper.

BNEF says on its trajectory for coal and gas prices is “significantly lower” than the 2015 edition did a year ago.

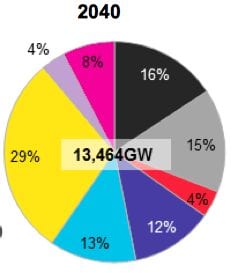

The forecasts (see chart above) show that solar will dominate new installations, accounting for 43 per cent of all new capacity additions out to 2040, or more than $US3 trillion. Solar and wind together account for 64 per cent of all new capacity additions, and flexible capacity – such as battery storage – is the next biggest contributor.

The amount of new coal capacity falls sharply after 2020, gas provides only 16 per cent of demand – well short of the “golden age” predictions of just a few years ago, and there are negligible amounts of new nuclear installations, due to its prohibitive costs.

The NEO 2016 is based on a combination of the project pipeline in each country, current policies, plus modelled paths for future electricity demand, power system dynamics and technology costs. It does not assume any further policy measures post-2020, to speed up decarbonisation.

But it says that decarbonisation will need to be more rapid to meet the 2⁰C scenario agreed in Paris, let alone the 1.5°C scenario.

On top of the $US7.8 trillion forecast in this report, BNEF says the world would need to invest another $US5.3 trillion in zero-carbon power by 2040 to prevent CO2 rising above the ‘safe’ limit of 450 parts per million.

(The full report is available only to clients of BNEF).