Whichever way you look at it, someone is going to get burned by the asset sale process of the NSW electricity network operators – or at least the three entities that will be partially sold, or leased. And that somebody will most likely be the consumer.

The NSW government had hoped to get around $13 billion from the sale, a sum it promises to spend on planes, trains and automobiles (airport access, network extensions, and new roads).

It’s probably going to get less than that now. Just how much is still being crunched by the analysts, and will likely depend on appeals to a pricing tribunal. But it could have been much worse for the government. Instead, it’s much worse for the consumer.

As we reported yesterday, the big ticket items in the AER ruling were the cuts allowed expenditure, on average around one third less than what the networks wanted.

One of the main reasons was the big cut in allowable returns on capital. Where once the networks were allowed double digit returns on capital, that has been slashed significantly in the latest ruling.

Part of that has been due to the fall in interest rates and bond rates. For the NSW generators, this meant a big cut, now to an average 6.68 per cent. For the privately owned Spark Infrastructure, and its network in South Australia, it means its weighed return on capital being slashed to 5.45 per cent.

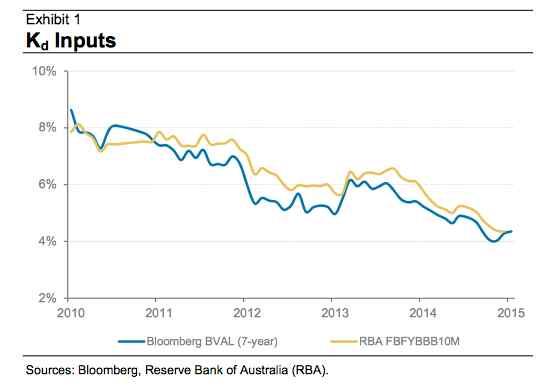

Rob Koh, from Morgan Stanley, noted in a report today that the difference is explained by the timing of the cost of debt setting. The cost of debt inputs have fallen 70 basis points in the last six months, and the AER is obliged to take a 10-year trailing average on the basis of that input.

SA Power Networks is being allowed a cost of debt of 4.35 per cent, which Koh says is “uncomfortably close to current real-world debt market levels.”

Had the debt markets been that low for the NSW settings, it might have doubled the savings – of between $160 and $300 a customer – that the AER says will be pocketed by the reduced spending allowance. And it would have cost the government potentially billions in lease revenues.

As the AER explained in an emailed statement: “The cost of debt for NSW and SA were set at different points in time. The cost of debt for NSW was set prior to 1 July 2014 while the cost of debt for SA was set recently.

“Interest rates have decreased significantly since the NSW rate was set. The earlier date was used for NSW because its regulatory period was due to commence on 1 July 2014, but the decision was delayed by the AEMC to allow the new national electricity rules developed in 2012 to be applied to NSW decision.”

In effect, the AER says that it has no choice.

For Koh, and others, it underlines one of the frustrations of the electricity market, its complexity and archaic rules that inhibit rapid change.

And the big question is whether the networks will actually change their spots. Much has been written, both in RenewEconomy and by the regulators and network operators themselves, about the need to adapt to the rapid changes in technology that will shift the business from a centralized model to at least a partially decentralized grid.

There’s not a lot to show that policy is keeping pace. The AER – on the basis that the AEMC has not finally its drawn out policy revisions – is not yet allowing expenditure on alternatives to simply building or upgrading poles and wires. In the end, that could cost customers even more.