Four major leaks were discovered this week in the two pipelines that usually shuttle gas from Russia to Europe, in what is now regarded as the biggest single methane leak ever recorded.

NATO has labelled the suspected sabotage of the Nord Stream gas pipelines 1 and 2 in the Baltic Sea as “deliberate, reckless and irresponsible acts”.

The pipelines in question have been at the centre of a storm of controversy for months as Russia cut gas supplies to Europe amid mounting tensions over the war in Ukraine.

Before the war in Ukraine, Russia supplied more than half of all the gas used in Germany and more than 40% of the EU’s gas needs.

In response to sanctions against Russia, however, Nord Stream 1 operated at a fraction of its capacity over summer, while Nord Stream 2 never opened.

Largest leakage of methane in a single event ever recorded

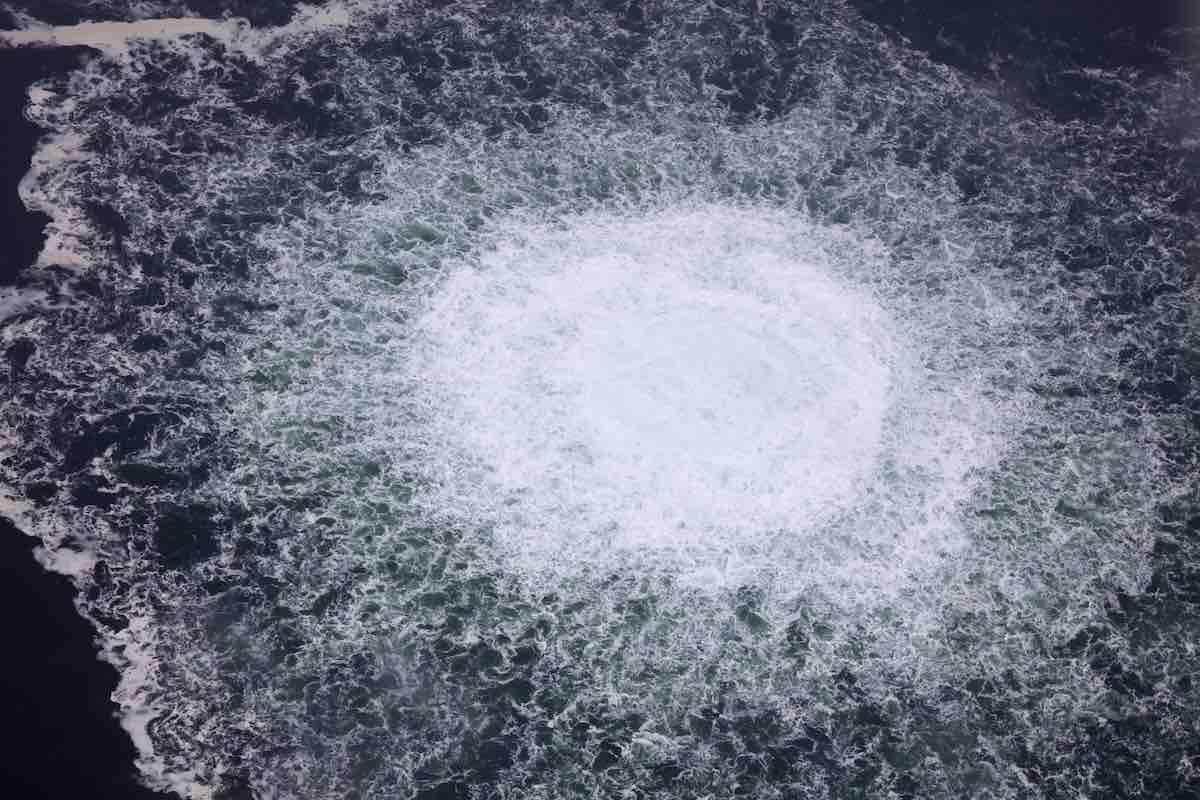

Though not in operation, the two pipelines were still full of gas, and are now haemorrhaging methane – a greenhouse gas at least 25 times more potent than CO2 over a 100-year time frame – into the atmosphere from four seething patches of the Baltic Sea.

The four leaks are the largest cumulative leakage of methane in a single event ever recorded. Deliberate sabotage was seemingly confirmed by reports from Seismologists in Sweden and Denmark earlier in the week of several powerful explosions in the area.

Billeder fra F-16 af gaslækage i Østersøen. https://t.co/OgCDfcvTjG pic.twitter.com/D5wsoXvuda

— Forsvaret (@forsvaretdk) September 27, 2022

Speaking with ABC News, Stanford University climate scientist Rob Jackson labelled the sabotage “war crimes”.

Though most governments have fallen short of naming Russia directly responsible for the explosions, Poland’s foreign minister has called the leaks ‘an element of Russian hybrid war’.

What is the climate impact?

It’s unclear how much gas was in the pipes, but according to Kristoffer Böttzauw, director of the Danish Energy Agency, the leaks may amount to about 14 million tonnes of CO2, roughly 32% of Denmark’s annual emissions – and Denmark and Sweden will have to include the leaks within their annual climate reporting.

It looks as though these leaks will be less damaging to the climate than the headlines might suggest, however: the US Geological Survey estimated the total amount of methane released would amount to about 0.1% of annual global methane emissions.

Similarly, British climate scientist Chris Smith tweeted on Thursday, “I ran the numbers on the #NordStream methane leak and thankfully the climate impact is small: median additional warming of 0.000016C that peaks by 2030.”

“They’re pretty small in the global context but very big by comparison with other leaks we know about,” said Peter Rayner, a professor of climate science at the University of Melbourne.

“Anthropogenic emissions of methane are in the hundreds of millions of tonnes each year and one estimate for this is half a million so it’s a big event but not a long-term story.”

According to Drew Shindell, a professor of earth science at Duke University, US, the emissions rival those of a medium-sized city.

“It’s not trivial, but it’s a modest-sized US city, something like that,” Shindell told the Washington Post. “There are so many sources all around the world. Any single event tends to be small. I think this tends to fall in that category.”

Impact on marine life

Concerns were also raised about the potential impact of the leaks on the environment and marine life of the Baltic Sea.

A spokesperson for Germany’s Environment Ministry told Deutsche Welle, “according to our current knowledge, the leaks in the Nord Stream pipeline do not pose any serious threat to the marine environment of the Baltic Sea.ʺ

While the potential for explosions near to the leaks pose a present threat to marine life – and boats – nearby, the long-term impacts look to be minimal, as all the methane will either escape into the atmosphere or be consumed by microbes in the water.

“I’m not a toxicologist so I can’t comment on acute toxicity but this stuff will disperse pretty quickly into the ocean and the atmosphere provided the leak has stopped,” Rayner said.

Will the leaks affect Australian gas prices?

The leak announcements led the price of natural gas per megawatt-hour in Europe to rise 12.8% on Wednesday to €209.88 (AU$317.24), despite the fact that both pipelines at the time were sitting idle, loaded with gas not bound for anywhere.

Perhaps more alarming, Kremlin-controlled gas company Gazprom this week threatened to halt gas supplies to Europe via Ukraine by imposing sanctions on Naftogaz, the Ukrainian gas company.

This latest surge in gas prices comes after several weeks of decline thanks to European efforts to bolster gas supplies ahead of the coming winter.

While Australia’s gas prices have risen, they have tailed behind soaring European prices. Nonetheless, gas price hikes affect every facet of the global market, and the resultant economic damage is exported around the world by the rise in other costs.

“I think it’s probably not yet clear how this will affect other regions,” said David Frame, director of the New Zealand Climate Change Research Institute (NZCCRI) at the Victoria University of Wellington.

“Those most directly affected will be in Europe, though also potentially in other places in Eurasia which utilise piped gas if they perceive risks to their supplies to be elevated. Beyond that, it’s hard to know.”

But Frame acknowledged that the crisis is likely to ripple outwards into other areas.

“Europe will presumably be increasing its demand for other fossil fuels to see them through the energy disruption, and that might push other fuel prices up,” he said. “It’s hard to say at this point, I think.”

Can the leaks be repaired easily?

Germany’s security agency believes the damage may have made the pipelines ‘unusable forever’, as reported by Tagesspiegel. And technical experts say the pipelines will be harder to repair once all of the gas has escaped and they fill with seawater and start to corrode.

Any attempt to repair them before that point would be too dangerous, however, because methane gas is highly flammable and therefore explosive.

It’s the final nail in the coffin for the old world-order of European reliance on Russian gas. But what’s the solution?

Another boost for renewables?

According to Rayner, this new twist in the beleaguered story of the European gas crisis may ultimately propel the shift to renewables.

“They’ve a short-term problem (this winter) and a longer-term one if supply stays blocked,” said Rayner.

“They won’t be able to switch their energy system overnight so they’ll probably use gas plus potentially reopen their mothballed coal and nuclear plants, but I suspect they’ll never risk dependence on Russian gas again, probably accelerating the renewables switch.”

“I hope this will focus minds on moving away from reliance on fossil sources of energy, especially where these can be used as geopolitical bargaining chips,” added Frame. “It’s an obvious lesson but one that appears to need to be learned every few decades.”

Note: This story has been updated to remove the reference to LNG.