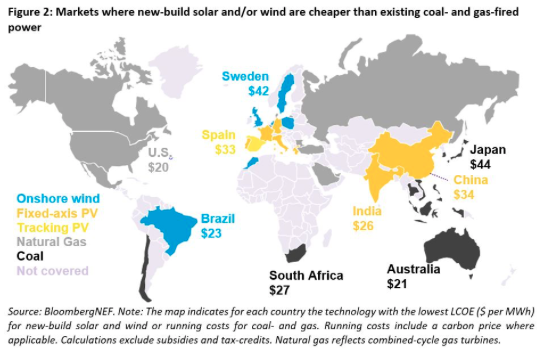

It is now cheaper to build and operate new utility-scale solar photovoltaic farms in much of the world than it is to maintain existing coal-fired power stations – though not in coal-rich, carbon price-free Australia, new research by BloombergNEF finds.

It’s already well established that the plummeting cost of solar PV and wind means that when a coal plant reach the end of its life, it makes no financial sense to build a new one – even before you consider climate change and carbon pricing.

But the BNEF report suggests this dynamic has moved to a new plain, and could potentially prompt coal plants in India, China and much of Europe to be shutdown early.

In Australia, though, where coal is plentiful and generators are not encumbered by carbon pricing like they are in Europe, it remains cheaper on average to keep existing coal plants running than to build and operate new solar or wind farms. That suggests economics alone are not yet enough to accelerate the transition away from coal that is already underway in Australia.

However, the news will be another nail in the coffin for Australia’s huge thermal coal export industry. It will raise more questions, for example, about the financial argument for developing Adani’s Carmichael thermal coal mine – the coal from which is earmarked for export to India.

Globally, BNEF says the levelised cost of energy (LCOE) – a measure which includes capital investment in a new project plus the cost to operate – of solar is now $US48 per megawatt hour. For onshore wind, it is $US41 per MWh.

In China, which is both the world’s biggest CO2 emitter and the biggest consumer of coal-fired power, the LCOE of solar is now $34 per MWh, one dollar cheaper than the cost of running a coal-fired power station.

It’s a similar story in India, where the LCOE of solar is $25 per MWh, and the average cost of running existing coal-fired power plants is $26 per MWh.

BNEF said India and China together account for 62 per cent of the world’s coal-fired power capacity, emitting 44 per cent of the world power sector emissions – amounting to 5.5 billion tonnes of CO2 a year.

In much of Europe, building new solar and wind farms is also now cheaper than maintaining coal plants – a dynamic that has been helped by a rocketing carbon price in the European Union’s Emissions Trading System.

In Germany, the EU’s biggest emitter and still a significant user of coal-fired power, it now costs on average $US85 per MWh to operate both coal and gas plants. That compares with $US50 per MWh to build and operate a new solar farm, and $US51 per MWh for onshore wind. Offshore wind, though, remains more expensive than coal.

As the chart below shows, the cost of generating electricity with coal and gas in Germany has shot up over the last year or two, in line with the carbon price – which went from less than €20 a little over a year ago, to more than €50 today.

In Spain and France, the levelised cost of new solar farms is now lower than the cost of running coal plants, while in the UK, Sweden, coal-hungry Poland, and Brazil new onshore wind is cheaper than existing coal.

But in Australia, which is richly endowed with coal in mines that are often right next to the coal plants they feed, existing coal generation remains more economic than it would be to build a new wind or solar farm. According the CSIRO’s GenCost report back in December, the levelised cost of new solar is between $35 to $40 per MWh mark ($US26 to $US30), while BNEF found the cost of coal generation is around $US21 per MWh.

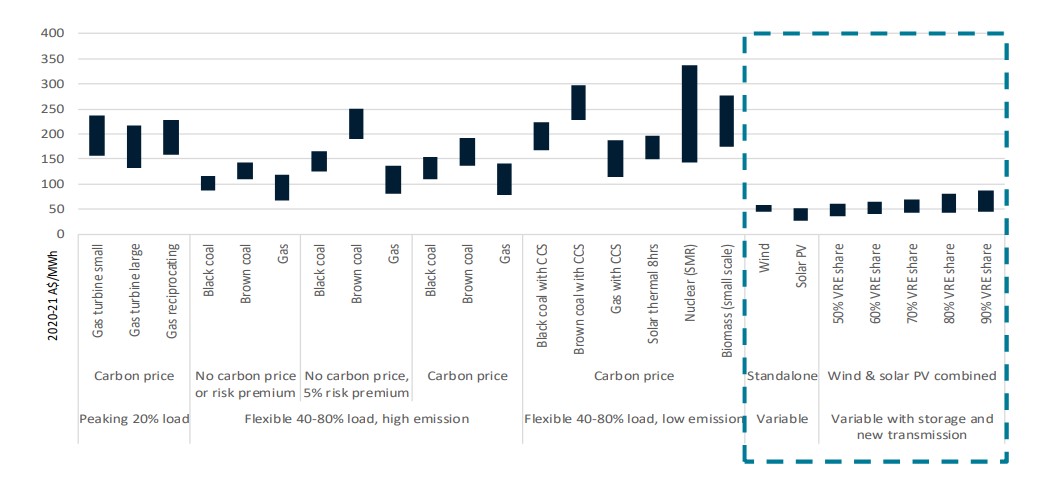

However, as the chart below shows, the LCOE of wind and solar is far cheaper than the LCOE of new coal and gas plants, even when you add in the cost of transmission and storage.

The increasing competitiveness of wind and solar continued despite spikes in the price of certain commodities needed in their production – including iron ore and polysilicon – over the last year.

This drove a 7 per cent increase in PV module prices in China during the second half of 2020, and 10 per cent increase in India, BNEF said. Similarly, it found wind turbine prices in India were up 5 per cent.

But BNEF said the commodity price hikes should be seen in perspective. “First, manufacturing, not materials, makes up most of the final costs for wind turbines, PV modules and battery packs. Second, supply chains will absorb part of that rise, before it affects developers. Third, some developers have longer-run purchase orders that might shield them against this rise for some time,” it said.

Tifenn Brandily, lead author of the report and associate at BNEF, said: “The economic incentive to deploy large amounts of solar power just got stronger in India, China and most of Europe. If policy makers can recognise this swiftly, this could prevent the emission of billions of tons of CO2.”