Garry Weaven, the head of leading investment group Industry Funds Management, has criticised the broader investment community for their “herd mentality” in continuing to support fossil fuel technologies, which he described as a bet that “vested interests” would win out over political and social leadership on the issue of climate change.

“Fund managers have been slow to invest in a low carbon future,” he said in a briefing on Friday. He said investment continues unabated in coal and fossil fuels, a bet which relies on vested interests prevailing over public policy, and the lack of a meaningful price on carbon needed to avoid runaway global warming impacts.

The comments came in a briefing hosted by the Australian Science Media Centre in the lead-up to the international climate change talks that resume in Doha next week. It follows a week when numerous international reports – from the International Energy Agency, the World Meteorological Organisation, the World Bank, the UN and PwC highlighted how dangerously close the world was to missing its climate change goals and locking itself into potentially devastating climate impacts.

Weaven was particularly critical of the “herd” mentality of the investment community, and their focus on short term benchmarks. “They are driven not by fundamental research into risk and reward, but by the risk that they might lose business on short term underperformance,” he said. “There is a huge degree of herding around a common benchmark. “

But, if – through changes in policy and a move to low carbon world the axis on which they are measured can be shifted – then they will quickly move to herd around that. “We have got $1.5 trillion (in the Australian funds management industry), and if that was effectively mobilized it could rapidly change the face of the energy industry in Australia.”

Weaven said the difficulty in dealing with the political power of vested interested had been highlighted in the current debate around the Renewable Energy Target. (IFM owns Pacific Hydro, the largest independent investor in renewables in the country).

“We have an acute problem in the clean energy debate with the political power of vested interests,” he said, noting that Australia – despite its low debt levels, and low unemployment, had found it hard to invest in renewables. He said that the 20 per cent target – or the fixed target of 41,000GWh that is currently being attacked by generators and utilities – was a “very modest” target, but it was struggling to hold on to even that.

“It is an inadequate response from high carbon country, but it is a significant change from where we are at the moment.” Yet, he said, two of the biggest utilities in the country – Origin Energy and EnergyAustralia – were behaving as though preparing for a future dominated by vested interests.

Weaven also highlighted the prospect of the “carbon bubble”, where investors find themselves stranded by investing in fossil fuels which can not be extracted if the world is to meet its climate change targets.

Ian Dunlop, a director of research group Australia21 and a former head of the Australian Coal Association, said that the emissions profile was hitting the worst case scenario. “In 20 years, we have done nothing to limit those emissions, despite the rhetoric going on and efforts through the UN and otherwise. The official target is far too high. We are going to have to set our sights at far more stringent approach.

He reiterated the International Energy Agency’s conclusion that if the world was to meet a 2C target, then it could only burn around one third of the existing proven reserves of oil, coal and gas. – and you look at proven fossil fuel reserves in world. We can only burn around one third of current existing proven reserves.

“We are going to have to be put on a low carbon footing extremely rapidly,” he said. And he repeated his warnings about the impacts of “peak oil”, saying that the current rush to shale gas, and to shale oil, was unsustainable – both in production and environmental terms.

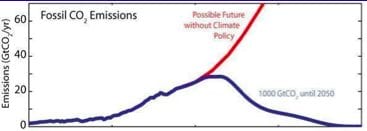

David Karoly, professor of Climate Science at The University of Melbourne’s School of Earth Sciences, said the latest science suggested that the world had to cap cumulative emissions from 2000 to 2050 at about 1,000 gigatonnes (one million tonnes of CO2e). It was already well over 500GT and was on target for 2,500GT on its current trajectory.

In another measure, the world needed to keep emissions at below 450 parts per million, but it was already above 470ppm and on its way to 900ppm.

He provided this graph (above) to highlight where the world was headed with emissions with no climate policy, and where the world needed to be to meet the science. “This requires rapid and large emission reductions now and net negative emissions by around 2070,” he said.