Australian regulators are finally waking up to the grim consequences of Australia’s archaic energy market design, and the fallout from the reckless and self-serving opposition to carbon pricing and renewable energy targets by the industry incumbents.

The Australian Energy Regulator’s latest State of the Energy Market report paints a frightening picture of how prices are controlled, manipulated and thrust into orbit by the cynical bidding practices of the major fossil fuel generators.

Consumers – both households and business – are paying the price, and they are faced with a double whammy, because as the Queensland Competition Regulator notes in its latest pricing report, it is the lack of renewable energy in the state which is allowing the coal and gas generators to set high prices.

This last bit of information is highly ironic, because the QCA, under the then leadership of Malcolm Roberts (not the Senator, but the current head of the main oil and gas lobby APPEA) was among those who used to rail against solar feed in tariffs and the like.

The then Queensland energy minister Mark McArdle argued that renewable energy would cause energy prices to surge. In fact, as anyone who was paying attention would have predicted, the opposite has turned out to be true.

So much so that the QCA now makes clear that it is the lack of renewable energy that is allowing wholesale prices to stay high. That’s because it means the market relies more on expensive gas to set the marginal price, but also allows the fossil fuel generators virtual carte blanche to manipulate the market.

This might be finally addressed by the current surge in large-scale solar plants and wind farms in the state’s north and south-west.

Certainly, some are waking up to it. Telstra is the latest, signing a contract to build a 70MW solar farm, while Sun Metals is building its own 116MW solar farm near Townsville.

Their motives, as they were for the Sunshine Coast council which is building its own 15MW solar farm, are to free themselves of the tyranny of the small cabal of coal and gas generators, that sets the wholesale price of electricity in the state.

The market power of major fossil fuel generators and their bidding practices have been highlighted in the AER’s State of the Energy Market report released this week, and is yet more confirmation about the poor design of market rules which leaves the regulator powerless to act.

The report acknowledges that the problem stems largely from the decision to allow generators and retailers to form so-called “gentailers”.

This has helped those big companies protect their own revenues through hedging, but also create an oligopoly that the AER says has posed a “potential barrier to entry” to new generators and retailers.

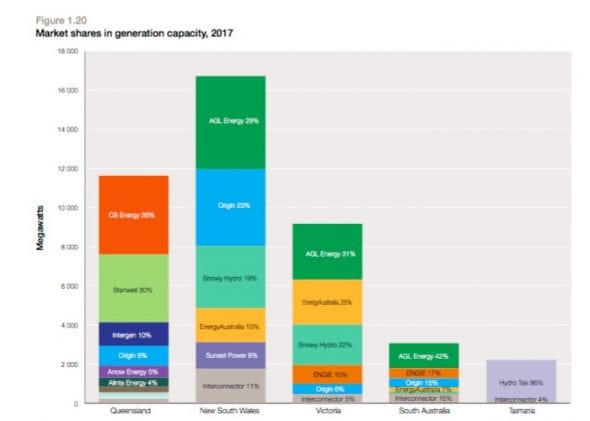

AGL Energy, Origin Energy and EnergyAustralia, it notes, supply 70 per cent of retail electricity customers in the NEM and have expanded their market share in generation capacity from 15 per cent in 2009 to 48 per cent in 2017. In some states, control of generation lies in the hands of just two or three major players.

This market dominance has reached such levels that it is the bidding practices of the generators – rather than the ratio of renewables or even soaring gas prices – that is having the major impact on prices that consumers pay.

“High levels of market concentration and vertical integration between generators and retailers lead to market structures that may provide opportunities for the exercise of market power,” the AER says.

This is especially the case in South Australia, where the AER says the major contributing factors are the region’s “relatively concentrated generator ownership, generator bidding behaviour, thermal plant withdrawals, and limited import capability.”

And it is occurring in Queensland too, another state where the market is dominated by just a few, government-owned generators, and where prices have jumped to “unprecedented” levels of around $108/MWh in the first nine months of the 2016/17 financial year.

“Opportunistic bidding by large generators has caused periods of spot market volatility in Queensland for several years, typically during summer,” the AER report says.

“For example, generators periodically rebid large volumes of capacity from low to very high prices late in a trading interval, typically on days of high energy demand and when import capability on transmission interconnectors was constrained.

“By rebidding late in a trading interval, other generators lacked time to respond by ramping up their output. Given the settlement price is the average of the six dispatch prices forming a trading interval, a price spike in just one dispatch interval can ow through to very high 30 minute settlement prices.”

This effective rorting of the market has been highlighted repeatedly by various studies, including by the Melbourne Energy Institute.

It is the reason why Sun Metals led the push to a 5-minute settlement period – a proposal backed by the Australian Energy Market Operator and others as a means to stop this practice, but which has been fiercely rejected by all the major fossil fuel generators.

The AER report goes on in some detail to show how generators in Queensland rebid capacity into high bands on days hot weather and strong demand, and particularly when their were constraints on imports from interstate.

This, as we have noted, does not just happen in Queensland and South Australia, but happens more often because of the fact there is limited lines interstate.

This manipulation of the market – which has now riled the network operators as well – is further illustrated by examples the AER cites of generators deliberately withdrawing capacity when prices rise.

As might be expected for a rational business in a competitive market, large generators do tend to produce more output as prices rise—at least to around $100 per MWh. But, in each region in the years to 2015-16, generators sometimes reduced their output when prices rose above $100 per MWh.

“This behaviour may be explained by deliberate capacity withholding to tighten supply and thus influence prices.”

It says other possible explanations include the inability of some generation plant to respond quickly to sudden price movements, or the fact that they sometimes fail in the hot weather.

It is all, apparently, quite legal, which shouldn’t be surprising given that the fossil fuel industry has been allowed to pretty much write the rules of the energy market to fit its own business model and revenue objectives.

But it does underline the case for a change in rules that can encourage a more diversified, more competition and more technologies – such as battery storage and demand control.

As AEMO, ARENA, CEFC and many others have emphasised, this market needs a radical overhaul, and it should not be left in the hands of the current rule-maker, the Australian Energy Market Commission, to do this.

The “unstoppable” transition to a renewable-focused, decentralised grid is likely to face some hurdles.

As former US defence secretary Donald Rumsfeld used to say, there are “unknown unknowns”, such as the fault ride-through settings on wind farms in the September black-out, and with gas generators and coal generators before that.

There are also known unknowns, such as the amount of inertia and synchronous energy that will be required in a grid powered mostly by wind and solar.