Norfolk Island, the former penal colony and now tourist destination located nearly 1,500km off the east coast of Australia, is calling for proposals for energy storage to maximise its use of solar PV, minimise a growing “solar debt,” and cut its crippling electricity costs.

The island, with a population of around 1750, and a floating tourist population of 300-600 people, has one of the highest penetrations of rooftop PV, with 1.4MW of solar that produces more than its daytime demand.

This is despite the fact that the Norfolk Island regional council actually brought the installation of solar PV to a halt in 2013 with a moratorium designed to stop the “ad hoc” installations, and because it had no other means of controlling and managing the output.

This is despite the fact that the Norfolk Island regional council actually brought the installation of solar PV to a halt in 2013 with a moratorium designed to stop the “ad hoc” installations, and because it had no other means of controlling and managing the output.

Now, things have changed.

The cash-strapped administration wants to try and store the excess output of solar so it can reduce its reliance on diesel, cut its hefty electricity charge of 62c/kWh (unlike other islands, like King Island, it gets no subsidies), address the growing bank of “grid credits” given to those who produce excess power from their PV and perhaps allow more people who don’t have solar PV to add it to their rooftops.

Back in 1997, the council bought the last of its six second hand 1MW diesel generators, partly on the assumption that demand would grow. Instead it has fallen around 20 per cent, and it only ever uses two of the units at most, and outside peak times it uses only one.

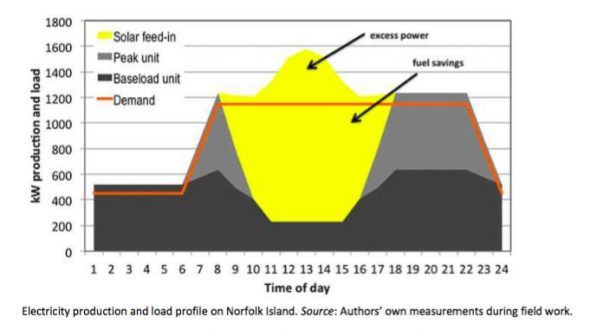

The council says the oversupply of solar is occurring each day “at all times of the year and not only in summer” when the sun is out.

The council says the oversupply of solar is occurring each day “at all times of the year and not only in summer” when the sun is out.

Because the diesel generator needs to operate at a minimum 30 per cent capacity, excess solar output is shed via a 400kW load bank. Excess solar did not get a cash tariff, but grid credits that are now amassing into a considerable continent liability.

“The fuel savings from less usage of diesel in the daytime have not been matched by actual savings as, effectively, those PV consumers (generating more than they or their fellow consumers are using during daylight hours) are resulting in the need for Norfolk Island Electricity (NIE) to shed the excess in daylight whilst then burning diesel at night time to supply both PV and non-PV connected households at no/limited cost to the PV consumer.”

So, now it is is looking for battery storage as part of a wholesale review of its pricing structures, and as the administration comes under pressure from households that have not been allowed to install solar PV, but can clearly see it as a cheaper option than the current grid prices.

“This opportunity is for one or more persons or organisations to develop and supply a solution, or set of solutions, for Norfolk Island’s current problems of energy oversupply during peak periods of solar insolation and concurrent inability to store this oversupply for later use,” it says.

It is also inviting tenderers to think about other solutions, too, such as energy efficient lighting, demand management and electric vehicles.

In the past, the island has commissioned studies into wind turbines, biogas, large-scale solar, wave energy, and mini-hydro. But, for one reason or another, none suited. And all have since been sidelined by the rush to cheaper and more easily installed rooftop PV.

“Norfolk is no longer a “green-field’ site and with 1.4MW of consumer -wned distributed PV, has a different set of challenges,” it says. “Better utilisation of what we have now and integrating it with some other power/storage is a high priority.”

The other challenge the island faces is that the administration is cash-strapped – and one of the prime motivations for moving now is the growing bank of “grid credits” that it needs to address. The island is also remote, and it has difficult access.

Energy experts often point to so-called “duck curves” in the California market and in Queensland, due to the growth of solar, but Norfolk Island is well ahead – in fact, it is already dealing with the excess of solar output over demand that is predicted for South Australia, Western Australia and Tasmania in the next 10 years.

Look at the graph above and contrast the dark blue dotted line across the top (load in pre-solar 1998) with the purple dotted line representing load in 2013. Note those dips in the early afternoon as the solar PV winds up in summer and winter (circled line).

Below is another representation, showing a cloudy morning in summer, but solar peaking well above demand, but having to be shed because the diesel generator can’t run at less than 30 per cent capacity.

(Unlike in King Island, where the hybrid project succeeds in switching off diesel altogether for long periods of time. Presumably, that is what the tender is about).

The island’s peak – last measured in 2013 – has not grown at all, and is around 1.3MW to 1.6MW, usually in mid to late morning as the tourist population have a “leisurely start to the day” and shower and have breakfast.

The evening peak is a little smaller, also based around “food preparation, dining, and entertainment and showers”, and there is no industry in the island to drive significant daytime load. And the declining population has resulted in a 20 per cent fall in demand over the last 15 years, along with the self-consumption of solar PV.

The total capacity of 1.4 MW installed distributed PV has since been estimated to generate an average of between 5,000 and 6,000 KWh per day (over a whole year) of which approximately half is estimated to be usable if returned to the grid.

This assumes 88 per cent shade free and a less than optimal installation. In common with many other jurisdictions, not all PVs have been installed with optimum orientation of solar. It is estimated that 50 per cent have been installed at optimum orientation and angle.

Expressions of interest are due in the first week of May.

This article was originally published on RenewEconomy sister site, One Step Off The Grid. To sign up for the weekly newsletter, sign here.