Large energy users, battery storage developers and some small energy retailers are pushing for a change in energy market rules that could have dramatic consequences for the industry – levelling the playing field for battery storage, lowering prices for consumers, and wresting control of the energy markets from the big generators.

Soaring wholesale prices have become a major issue in Australia in recent months, defying logic (analyst David Leitch has described them as absurd), and raising concerns among many energy consumers.

The finger has been pointed at the bidding patterns of some major generators, which is one of the main reasons why the South Australian government wants to build a new cable to the eastern states, because it says it has “lost control” of energy pricing. (Although some media chooses to blame renewables).

The proposal to change a relatively obscure rule in the running of the energy markets is seen as an opportunity to wrest control from big, bulky, slow-response generators and encourage smarter, smaller, fast-response distributed generation, particularly battery storage and software for energy management systems.

The proposal comes from zinc smelter operator Sun Metals, which has asked the Australian Energy Market Commission to change the rule. Currently, pricing is set every five minutes, but financial settlement is made only every 30 minutes. Even the AEMC admits that this can distort the market, and push up prices unnecessarily.

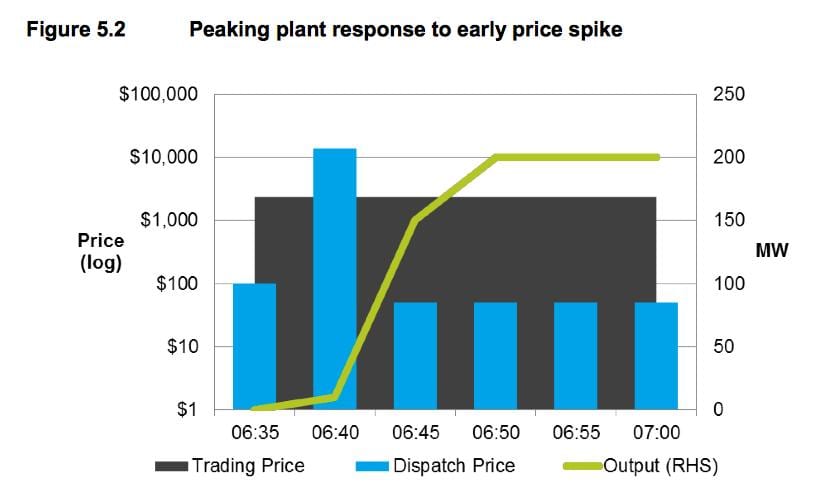

An example is illustrated in the graph below, which explains why operators of big generators, particularly gas or diesel-fired peaking plants, may object to the rule change.

In this scenario, the dispatch price is $100 per MWh in the first five minutes, leaps to $13,800/MWh in the second, and falls back to $50/MWh for the remainder of the half hour.

The trading price for the half hour is therefore averaged out $2,350 per MWh. Under current arrangements, the generator would receive just under $149,000 for this trading interval, but only $15,000 if it was settled on a five minute basis. That will deliver big savings to consumers.

Sun Metals is pushing the “five minute settlement rule” because it says current arrangements “accentuate” strategic late rebidding, “where generators have been observed to withdraw generation capacity in order to influence price outcomes.” In other words, it accuses generators of acting artificially to create a price spike.

Sun Metals also says the current arrangement impedes market entry for fast-response generation and demand-side response, and specifically battery storage, which can respond to changes in demand in a fraction of a second, far quicker than most gas-fired generators.

Its submission says that having financial settlement every five minutes will provide a better price signal for battery storage and other technologies to respond to price signals. If they respond to one five minute interval, but fear that the price may be brought down by the half hour average, there may have no motivation to bid.

Similarly, a zinc smelter operator like Sun Metals may also find it more disruptive to try to control its own load for a full 30 minute period rather than a five minute period.

The Sun Metals proposal has won support from small energy retailers such as Mojo Power, because it says it is an issue that impacts large energy users such as smelter, but will also impact small consumers such as households as battery storage becomes more widespread.

“The current mismatch between dispatch and financial settlement means that information isn’t clear enough for the demand side to efficiently respond to price changes,” Mojo CEO Jim Myatt says.

“These issues currently affect large customers, but will increasingly impact smaller customers as distributed generation and demand management technologies become available and cost competitive for homes and small businesses.

“Indeed, the current mismatch between dispatch and financial settlement should be seen as a significant barrier to the deployment of such technologies, and if changed to align settlement and dispatch the value equation for these technologies would fundamentally shift.”

Myatt cites an example in the current market framework, where a battery behind an end-use customer’s meter is directed to draw energy from the grid early in a 30-minute trading interval, only for the wholesale price to spike later in that period.

In this case the earlier direction to draw from the grid ends up being against the financial interests of the customer. A similar issue arises for a customer with a demand management system that operates early in the trading interval, on the assumption that the price will be low, only for the price during the trading interval to ultimately be high due to a late price spike.

Myatt says the long-term impact of a move to settlement on a five-minute basis would be a much more efficient wholesale market as well as more efficient markets for ancillary services.

“The change to five-minute settlement would connect the supply and demand sides of the wholesale market with real-time price transparency.

“This could really unleash the demand side because customers could make efficient usage decisions in the short term and efficient investment decisions – in things like batteries and energy management systems – for the long term.

“It would be a game changer because for the first time the incentives would be right for customer decisions around what they value to drive the market.”

But the proposal is likely to be opposed by owners of large generators, particularly those with existing generating assets that cannot respond as quickly to demand and supply changes and wholesale market price signals.

The position of “gentailers” – those companies with large generation assets but also promising a switch to distributed generation – will be interesting to watch.

“We think the impact of this on end-use customers would not be significant because the retirement of existing generating capacity would result from that capacity being replaced incrementally by cheaper and more flexible capacity (whether that is supply or demand side capacity),” Myatt says.

Unsurprisingly, battery storage developers are also on-side. Australian “Ultrabattery” developer Ecoult says the rule change could increase the opportunities for battery storage to become the most cost-effective solution to managing grid variability and peak pricing.

Ecoult says battery storage could also provide ancillary services such as frequency regulation, which has traditionally been the province of large generators.

“Unlike traditional generators, batteries can provide energy to the grid when it is undersupplied and store energy from the grid when it is momentarily oversupplied – energy that would otherwise be dissipated as heat.”

Ecoult says market conditions currently favour fossil fuel generators, but these are not the most environmentally sustainable way of providing short burstsof power.

“If energy storage was widely distributed, the grid would be less exposed to unexpected spikes in demand, and short-term price fluctuations may rarely take place,” it said.

Ecoult says 5-minute pricing may go some way towards allowing large battery owners to offer “generation” services to cover short peaks using energy stored from PV or during low-price periods.

“This is an important step because if there was a viable market for such services, the vast quantity of existing installed energy storage (acting as standby in data centres, utilities, hospitals and other critical loads) could be quickly adapted to create a large grid-connected variability-management storage resource.”

The AEMC recognises that 30 minute settlement was introduced because it was thought that the metering technology to make it shorter was not available. That has now changed.

The AEMC also notes that bidding patterns have been a problem, an issue also recognised by the Australian Energy Regulator. Another rule change, due to come into effect next week (July 1) also seeks to stamp out some strategic rebidding which it said was distorting wholesale price outcomes, and could create “false or misleading” offers.

The AEMC said the incentives on some generators to engage in strategic late rebidding were exacerbated by the mismatch between dispatch and settlement.