Australia is among the top seven countries worldwide responsible for 60% of the world’s biodiversity loss between 1996 and 2008, according to a study published last week in the journal Nature.

The researchers examined the conservation status of species in 109 countries and compared that to conservation funding. Australia ranks as the second worst of the group, with a biodiversity loss of 5-10%.

The study clearly linked adequate conservation funding to better species survival, which makes it all the more concerning that one of Australia’s most valuable national environmental monitoring programs will lose funding next month.

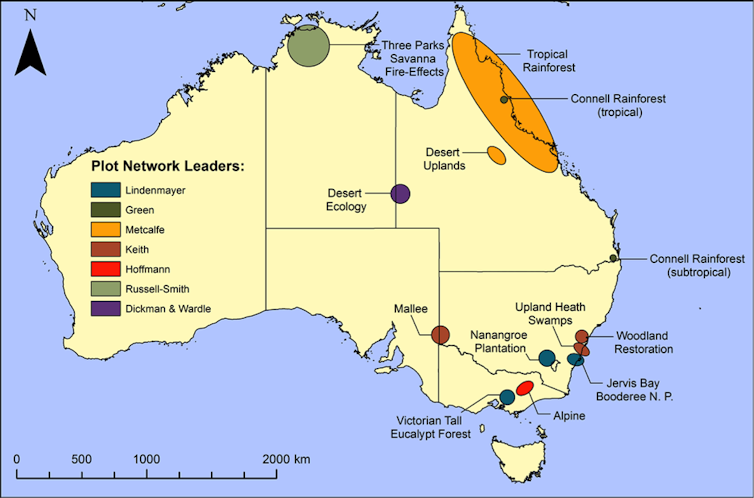

Established in 2011, the long-term ecological research network (LTERN) monitors alpine grasslands, tall wet forests, temperate woodlands, heathlands, tropical savannas, rainforests and deserts. It coordinates 1,100 monitoring sites run by numerous researchers, bringing together decades of experience. There’s nothing else like it in Australia, and at an annual cost of A$1.5 million it delivers extraordinary value for money.

The value of long-term research

Our continent has a hyper-variable environment, with catastrophic bushfires, alarming species extinctions, and widespread loss of habitat.

In the battle to manage and predict the future of our ecosystems, the LTERN punches above its weight.

In the Northern Territory it was long thought that the ecosystems centred on Kakadu National Park were intact. But instead, long-term monitoring showed alarming and unexpected crashes towards extinction of native mammals of the region since the 1990s, driven by fire regime changes, feral animals, disease, cane toads, climate change and grazing.

Likewise, the 70-year-old network of monitoring sites in Australia’s alpine regions revealed the impact of climate change on flowering pollination, and the fact that livestock grazing actually increases fire risk. Without these insights it would not be possible to manage these ecosystems sustainably.

In the Simpson Desert – the only LTERN site that captures the remote outback – the dynamic of boom and bust has been monitored since 1990. It reveals a long-running and cyclical explosion of life. Intermittent downpours support flushes of wildflowers, booming marsupial populations and flocks of budgerigars, which are then ravaged by feral foxes and cats. Spending only one year in the desert would mean missing this dynamic, which has driven dozens of native species to extinction.

Several of these monitoring sites are likely to close when funding stops next month, as alternative support is not available. Without the network, coordination among the remaining sites will become much harder.

We should be able to predict environmental changes

The National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Scheme, which ultimately funds the LTERN, has called for the development of a national environmental prediction system to forecast ecosystem changes.

But without long-term data, the development of a reliable and accurate environmental prediction system is impossible, particularly for biodiversity.

The journal Science reported in August that researchers working with LTERN are trying to find alternative funding, possibly for a more comprehensive network. But with limited funding commitment and opaque long-term plans from government, this seems ambitious.

After 40 years working in Australian ecosystem management, assessment, investigation and research, I am deeply concerned about terminating the existing system and starting again. It takes time to understand ecosystems, and the accumulated knowledge of up to 70 years of monitoring is invaluable. It risks destroying one of the few successes in long-term monitoring of our ecosystems and species.

Australia is infamous for commencing new initiatives and then stopping them. Australia’s surveillance and monitoring efforts are already recognised as inadequate. Breaks in continuity of long-term ecological datasets significantly reduce their value and disrupt key information on environmental and ecosystem change.

Out of step with the world

In a letter to Science, 69 Australian scientists described the decision to defund the LTERN as “totally out of step with international trends and national imperatives”. Indeed, the United States has recently expanded its long-term monitoring network, which has been running for nearly 30 years.

Not only is Australia’s decision against the international trend, it also defies Australia’s own stated goals. Australia’s Biodiversity Conservation Strategy explicitly commits to establishing a national long-term biodiversity monitoring system. The strategy’s five-year review admits to failing to achieve this outcome.

The loss of the LTERN will undermine assessments of the sustainability of key industries such as grazing and forestry. Without it, we can’t robustly evaluate the success of taxpayer-funded environmental management.

A$1.5 million a year is a very small price to pay for crucial insights into our continent’s changing environments and biodiversity. But reinstating this paltry sum will not solve the very real crisis in Australian ecosystem knowledge.

![]() We urgently need a comprehensive national strategy, as pledged in Australia’s Biodiversity Conservation Strategy. The evidence is in: investment in biodiversity conservation pays off.

We urgently need a comprehensive national strategy, as pledged in Australia’s Biodiversity Conservation Strategy. The evidence is in: investment in biodiversity conservation pays off.

Source: The Conversation. Reproduced with permission.