If you blinked, you probably missed it. The Golden Age of gas – which would usher in the transition from high polluting fossil fuels to clean renewables – is over. Probably before it even started.

The latest data from the Australian Energy Market Operator highlights just how quickly energy markets can change, and just how quickly they are changing.

Gas, the “clean fuel” whose demand was tipped to soar in a world intent on decarbonisation, is now no longer wanted. In the state of NSW, demand in 2019 is now expected to be 17 per cent below previous forecasts.

And to those manufacturers, gas suppliers and conservative governments who bleated about the need for access to highly contentious coal seam gas, and for new pipelines built across Australia because demand was running out, AEMO has a simple riposte: No, it’s not.

In fact, AEMO says there is no shortage of gas on the horizon, despite the massive appetite of the huge LNG trains being built in Queensland. There is no supply gap of any sort in the next five years, and the only supply gap over the next 20 years might be in Queensland, where more might be needed for power generation.

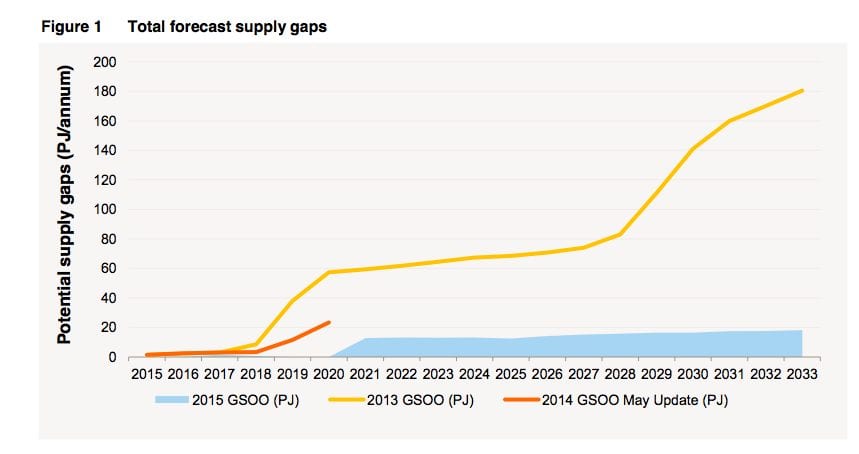

This graph above illustrates just how much the game has changed, so quickly. Just two years ago, the official forecasts were for significant gas shortages – which led gas players to put enormous pressure to exploit CSG, and the federal government to call for trans-continental pipelines.

Now there is barely any shortage forecast at all, ironically – and perversely – partly because Australia’s energy policies are now designed to support coal-fired generation, even though the country has way too much capacity.

This is a massive switch from what was the accepted wisdom just a few years ago. Then, gas was going to replace coal as environmental policies were tightened, and because it was best suited to act as a partner to renewable energy. But, in Australia at least, environmental policies have not been tightened, and there is a deliberate attempt to slow down renewables.

There is a whole host of reasons for the marginalisation of gas – some but not all of which could have been predicted when utilities invested billions of dollars building new gas-fired generation in recent years. (See graph above: The green and the red columns represent new baseload and peaking gas plant added in the last five years).

Part of the problem is prices. While international oil and gas prices are plummeting, gas in Australia is being priced out of the market because the benchmark price will now be set more or less by the export price. That means a near doubling in price over recent benchmarks. If international prices recover, it could mean a trebling in domestic gas prices.

The other problem is the removal of the carbon price. That makes gas much less competitive against the brown and black coal generators.

The black coal generators are replacing gas as the marginal cost of baseload generation. The Victoria brown coal generators are running close to capacity, and the black coal generators will pick up any slack.

That relegates gas to the role of responding to changes in peaks. That’s not particularly good for new baseload generators, because it is no longer profitable for them to run overnight in the hope of ramping up in higher demand during the day. These graphs – from Citigroup – show how the price of gas-fred generation is being pushed up by the rise in domestic gas prices.

Another reason is reduced demand. Industrial use is falling, and in other areas gas is being sidelined by competing new technologies. Homeowners and businesses are finding that technologies such as rooftop solar and, soon enough, battery storage offer a cheaper alternative for many of the functions performed by gas.

Battery storage could also reduce the need for some gas-fired generation at the utility level. As Paul McArdle is documenting in his series, the sizes of the peaks in Australian markets are simply not nearly as big as they once were.