Global investment bank UBS has conducted the first in-depth analysis of Labor’s proposed 50 per cent renewable energy target for Australia by 2030, concluding that it will require around $80 billion in investment, but much of this would need to be spent anyway.

In various scenarios outlined in the report, UBS says that up to 20GW of wind energy will need to be built by 2030, and 26GW of solar (both rooftop and large-scale), along with around $10 billion in grid costs. Around $4.8 billion is expected to be spent on battery storage by networks, and nearly $3 billion by households.

But it says this much of this will come from private investment, mostly from listed companies. And much of it needs to be factored in because it would be spent anyway to replace ageing coal and gas plants. And, UBS notes, all polls point to the popularity of renewable energy.

“A big part of the above cost will be incurred in one way or another as most of the thermal fleet in Australia is old and will need replacing.”

The intervention of UBS comes at a critical time, with the Canning by-election and leadership rumblings about Prime Minister Tony Abbott, who is implacably opposed to renewable energy, wind in particular.

Even Labor has not costed its own policy, or thought deeply about how it might attain its 50 per cent renewables target, agreed to at its recent national conference. But opponents have been focused on the nominal cost, just as they have on the potential cost of a 50 per cent emissions reduction target ($600 billion).

In labelling these costs, as the Abbott government and environment minister Greg Hunt has done relentlessly, assume that nothing is spent, or no effort is made to reduce emissions.

UBS says that the current target aims for around 7GW of wind and 6GW of solar, but it is not working anyway, because the policy certainty is not there – an issue we explore in this story, If wind energy is this cheap, why aren’t wind farms being built?

Indeed, UBS suggests that a reverse auction process might be the best way to meet a Labor 50 per cent target – the same system adopted with great success in the ACT, and now by Germany and Texas and elsewhere (South Africa, UAE and Brazil also come to mind).

“Renewable energy suppliers and financiers want revenue certainty,” UBS analyst David Leitch writes.

“Thermal suppliers want to be able to plan their future with confidence. We think capacity auctions meet both of these goals.”

How would this work?

Leitch says legislation could set a quantity of renewable capacity to be added to each year. For instance, a 50 per cent by 2030 target requires around 70TWh of new renewables to be delivered over the 13 years from 2018 to 2030. That’s around 5TWh per year.

“A capacity auction could be run, say, four times per year for 1.25 TWh of new renewable supply per year over 15 years. That would lead to 60 TWh of new renewable supply in a predictable fashion.”

And, he notes: “The objective is to have the costs passed on to consumers, but to ensure that the renewable supply is actually built. That is in contrast to the present scheme, where costs are passed on but there is not necessarily any new capacity.”

Leitch runs various models of how the target could be met. This is one of them.

As for grid stability, Leitch says the current system is already built to deal with massive swings in demand – up to 13.7GW over a single day, so the thermal generation system is actually more flexible than many think.

He points to this scenario on July 22, when wind went from 2.9GW to 0.6GW (see table below), but this was basically catered for by increased hydro and gas production. Demand during the day varied by over 4GW, with most of that adjustment coming from coal. The NSW coal generator Eraring doubled output over four hours.

But what happens with 50 per cent renewables?

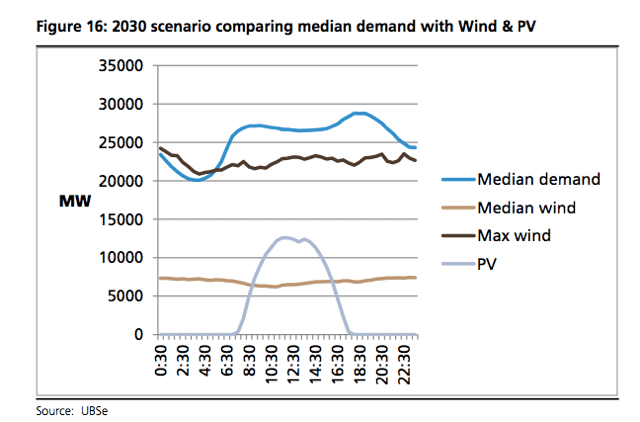

UBS says that under a relatively even spread of new wind and solar sufficient to provide 50 per cent of the NEM’s total electricity would see thermal electricity (coal and gas) having to go from a low of around 7 GW production to a high of over 20GW basically every day.

“Most of this change is relatively predictable and driven by the modelled 31TWh (15 per cent of today annual NEM energy) supplied by PV. However, the system also needs to allow for the volatility of wind.

“Based on wind’s measured variation between max and median output, we see potential for additional flex to cope with wind volumes falling below median levels. Wind could also produce much more than median level but, based on overseas experience, this would be managed by curtailment.”

The better answer would be in storage, and UBS sees a case for battery storage, and for incentives.

Some of this will come from households. UBS says grid-connected “hybrid households” – with both solar and storage – will be “both economic from the consumer point of view and desirable from the grid’s point of view.”

He suggests that one million households (just 15 per centof the 6.6 m households total in the NEM) with a 7 KWh battery would be capable of providing about 2-3 GW of power at any given time. We look into that aspect of the report in more depth here.