Global investment bank UBS has highlighted the challenges facing Australian energy utilities by suggesting that the falling cost of solar and battery storage means that the average Australian household could find it cost-competitive to go off-grid by 2018.

The report by its Australian based analysts says the current cost of going off-grid for a households consuming the average of around 7 megawatt hours would be around $39,000.

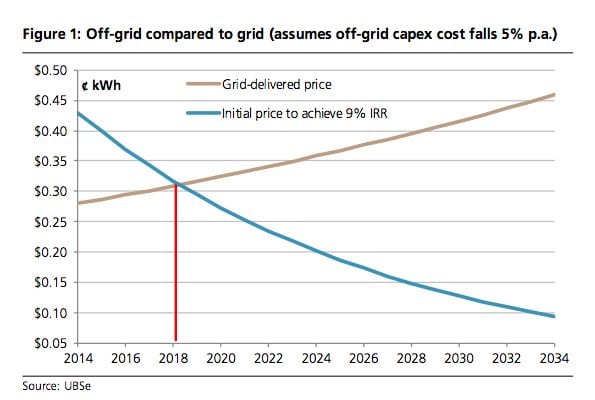

That translates to an average cost of around 44c/kWh for the life of the system. That leaves it in the hands of early adopters and hobbyists in the city, but assuming capital cost falls of just 5 per cent per annum, by 2018 it would become cost competitive for average households with staying on the grid.

For those in remote rural communities it may already be attractive – a situation recognised by Rob Stobbe, the head of SA Power Networks, who suggested last week that rural communities could soon decide that looking after their own energy needs will soon be a viable option.

The UBS conclusion follows recent reports from the Rocky Mountain Institute that suggested that households in major US cities such as New York and Los Angeles could find it cost competitive to leave the grid by 2020. Given that Australian households have far higher grid prices, it is not surprising that the inflection point could arrive earlier in the major capital cities such as Brisbane, Sydney, Perth and Adelaide.

This, of course, has major implications for both network operators and generators and retailers. UBS suggests Australian listed “gentailers” such as Origin Energy and AGL Energy are facing profit falls of around 10 per cent in coming years just from the anticipated growth in rooftop solar PV. UBS anticipates the amount of solar PV to grow to 5 gigawatts (up from just over 3GW now) in the next few years, and revenue and profits from retailers will fall as volume declines and discounts are offered to try and match the cost of solar.

It is the off-grid calculations that might ring the biggest alarm for incumbent industries. It is impossible to know how many households would choose such a route, but the UBS graph below highlights how attractive this might be over the next decade on current cost curves.

As RenewEconomy pointed out from the Energy Networks Association conference last week, there is a growing recognition, particularly among regional network operators, that a new business model is needed to deal with technological changes,

UBS takes up this point as well, but notes: “The current regulatory system for networks (cost minimisation) and the desire to protect the current asset base of the unregulated companies make them poorly placed and incentivised to respond to the disruptive change.”

This latter point is crucial because while some utilities recognise the changes that need to be made, the industry as a whole are fiercely guarding (as you would expect), the value of the assets that have been invested, including the around $45 billion allowed by regulators in the last five years – even though much of this has been criticised as un-necessary.

But such considerations may be forced upon them. UBS says the cost of solar is falling at an average rate of 5 per cent as the global deployment continues to surge. This means that even a decision by the “anti-renewable” Australian government to remove support measures, the fall in global prices would partly offset a potential 30 per cent cost increase in Australia.

It notes that lithium-based storage is starting to become commercially available and the cost currently comes to around $0.70 kWh of energy consumed. That is 40 per cent above the cost of grid-delivered electricity in Sydney, and while there may be limited scope to reduce the costs of the battery side of the storage devices, the balance of system costs could fall greatly if demand rises.

UBS argues that battery storage at the household level is likely to be most cost effective if the household remains connected to the grid, and simply uses the grid when storage is insufficient. “Since the current grid is largely a sunk cost there is little penalty to society for using the existing grid in this fashion,” it notes.

“Storage intuitively makes the most sense the further consumption is from production, i.e. where the grid costs are highest, as the regional networks with just three or four customers per kilometre of poles and wires. UBS notes that it is “interesting to obverse therefore that some of the network owners are now themselves looking at micro grids and community level storage.”

But other network operators and retailers are not responding in the same fashion. Tariffs for solar exports back to the grid are being cut, or exports made impossible, thus increasing the incentive for customers to install battery storage, even for those in the cities, and taking it beyond the “hobbyists” and early adopters and into the mainstream.

UBS cites several factors for this:

- Increased penetration of PV solar and the low export price for the electricity of those not receiving a feed-in tariff means that there is a ready market for storage if the price is right. As global decarbonisation increases it’s very likely that solar will become more and more attractive and therefore a bigger and bigger market for affordable storage will develop.

- Lithium ion technology has many of the characteristics required for residential storage: (i) it can be almost fully discharged without damaged; (ii) it’s less than half the size per unit of capacity compared to lead acid; and (iii) it’s capable of high energy output relative to capacity over a sustained period. Price is the problem.

- Driven primarily by Tesla Motors, electric car production is increasing – leading to increased battery production, with the stationary storage market expected to grow from 27MW in 2013 to 1,753 MW in 2022, with the market value soaring to $6 bn in 2020.

UBS notes that the cost of household storage varies, with some reports suggesting that lead acid battery storage can be achieved for less than $0.30/kWh. But it notes that the focus is on lithium technologies, and the economics of systems such as this of Zen Energy are coming down quickly.

“Based on about $30k installed for a system that can deliver 5 kW of power and 14 kWh for 3000 cycles, the cost per kWh comes to $0.71 kWh. This compares to $0.50 kWh for peak electricity in Sydney. In other words, it’s not economical yet, but it’s not hard to imagine costs coming down further over the next five years. The Zen system is packaged with the “command and control” system that decides what the household system should do at any time i.e. buy from grid, charge from solar or supply to the house.”