A few weeks ago when discussing some of the frustrations about the poisoned politics of solar PV over a pre-Christmas glass of wine, one solar industry executive ventured this idea: Maybe the only way to point out the value of solar PV is to switch off all modules at the same time on a sunny day. Then we might see what happens to the electricity market.

Of course, that would be impossible to do, and unwise to boot. But given the heatwave that has struck the southern states of Australia and the stress it has put on the electricity network, it might be worth pondering what might have happened if the country did not have the 3,000MW of solar PV strung out across more than a million rooftops.

The problem is there is no direct measurement of the PV output – just estimates – because a lot of the output is consumed at home, and is just not seen by the grid. There seems no doubt, however that solar has played a significant role in not just moderating demand, but also in reducing the severe pricing peaks that have occurred in recent years.

The Electricity Supply Association of Australia, which represents most of the networks and large scale generators that feed electricity into the grid acknowledges that solar was playing a role, although it described this as “small”.

The ESAA puts solar at just 2.5% of peak demand in Victoria at 3.30pm on Wednesday, and noted it produced the most at noon. It said that in South Australia, solar accounted for just 2 per cent at that state’s peak at 6pm on the same day.

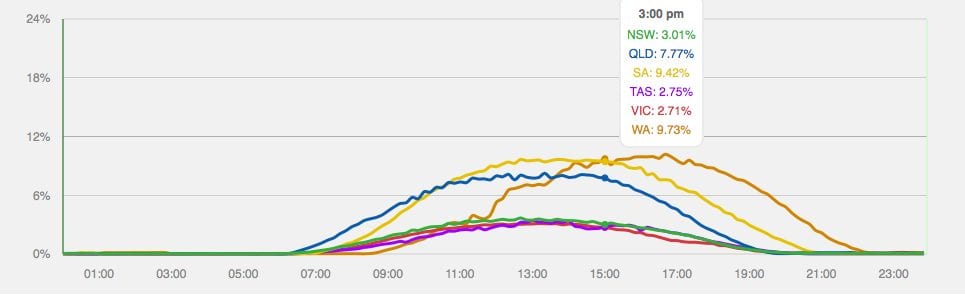

The Australian Solar Council, which represents the rooftop solar industry, puts the figures much higher. It said Victoria , and like other states, produced 2.80 per cent during peak periods, and in some states it was nearly 10 per cent.

9.41% in South Australia

9.13% in Western Australia

8.64% in Queensland

2.80% in Victoria

and 3.59% in NSW

It also noted that the output was pretty solid between 2:30pm and 5:00pm, at the hottest part of the day when electricity use is also at its peak.

This is borne out by data compiled by the Australian Photovoltaic Institute. The first graph shows what happened in Victoria, the second across the country on Wednesday. The APVI data suggests that the contribution of solar PV in South Australia at 6pm (local time) on Wednesday was nearly double that estimated by the ESAA – at more than 3.4 per cent.

As one industry analyst noted, the ESAA assessment of the impact of solar in South Australia misses the point. If it were not for solar, the peak would have been quite a bit earlier in the day and quite a bit higher (as it was in 2009). To put it another way, the peak has been pushed out to 6pm precisely because solar is no longer contributing much. So the solar contribution to reducing peak is much more than the ESAA comment implies, possibly by several multiples.

The second graph shows the contribution of solar on Thursday. If you go to the website, you can play with the graphs and adjust the times. It’s actually quite interesting.

There seems no doubt that solar is playing a key role in moderating demand and stress on the grid.

It’s interesting to note that the differences between the peaks of previous years – such as in 2009 when there was little solar – correspond with the amount of solar that has been installed (notwithstanding the need to add in population and air-con growth, offset by more energy efficient appliances and less manufacturing).

On Wednesday, for instance, the interval peaks were 10,110 MW in Victoria and 3,108MW in SA. The corresponding numbers on January 29, 2009, were 10,446 MW and 3,270 MW. According to the APVI’s Live Solar website, the PV contribution at the peak times was around 220 MW in each state. Some suggest that without solar, Victoria would have hit record demand from the grid on Thursday – and prices to boot.

In WA, the peak in electricity demand has fallen well short of previous years, despite the record-breaking streak of temperatures, rising population and growing use of air conditioning.

In 2011 and 2012, peak demand peaked at more than 4,000GW. In the past week, it made it only as high as 3,733. How much solar does WA have on its rooftops? About 340MW.

This has had an impact on peak pricing events. In 2009, the average spot price between 8am and 4pm was over $6,000/MWh. The average price – despite a few peaks – in the latest period has been about one tenth of that.

On Thursday, the volume weighted pool prices between 08.00 and 16.00 yesterday were $299/MWh in Victoria and $377/MWh in South Australia, despite the huge levels of demand. The reaching of super peaks of $12,000/MWh or more in Victoria occurred mostly when Loy Yang A – the biggest brown coal generator – had one of its four units off-line for urgent repairs .

Generators and retailers use elaborate hedging policies to reduce their exposure to such fluctuations – which can be triggered as much by bidding tactics and other factors as much as weather – but the fact remains that a large revenue pool has been evaporated by the impact of solar.

In the same way that one third of the network costs are to cater for about 100 hours of peak demand a year, generators source a huge amount of their annual revenue from similar events. The problem for many coal generators is that they grew to rely on these peak pricing events to boost their revenue, and inflate their values. Solar eats into those revenues whenever they produce – because the output comes during the day-time period, when prices are normally higher.

The financial advisors to the coal operators were so sure of the future that the coal plants were hocked to the eyeballs in debt, but when these pricing events started to decline, some generators – such as Loy Yang A – were barely able to meet even their interest payments, until AGL picked it up at a bargain basement price and refinanced and reduced the debt level.

In Queensland, the government’s antipathy towards solar may be explained by what it is doing to the state-owned generator, Stanwell Corp, which has more than 4,000GW of coal and gas fired generation, but didn’t make a single dollar in profit from those assets last year, only coal exports. It blames solar for putting into doubt the long term sustainability of its business.

One other graph is worth contemplating, and it is one that will continue to bedevil the established grid operators – be they networks, generators or retailers – and those who set policy and tariffs.

At the peak of demand the price in Victoria (and South Australia for that matter) made occasional jumps above $12,000/MWh. See the graph below, and thanks to Energy Matters for that one. As Energy Matters noted, the price of generation at those times was equivalent to nearly $13/kWh. The price of rooftop solar for households that had them? It would have remained constant – at just 13c-20c/kWh.