What does the fossil fuel industry make of the argument that it won’t be allowed to burn its main product?

What does the fossil fuel industry make of the argument that it won’t be allowed to burn its main product?

In 2011, campaign group Carbon Tracker warnedthat large portions of fossil fuel companies’ assets are “unburnable” if the world intends to limit global warming to no more than two degrees.

If energy companies can’t burn their reserves, they’re overvalued, the group argues, in an analysis aimed squarely at the world’s financial markets.

In the intervening years, the argument has gained some traction, including in key financial industry publications like the Financial Times and The Economist. But what do the fossil fuel companies themselves think?

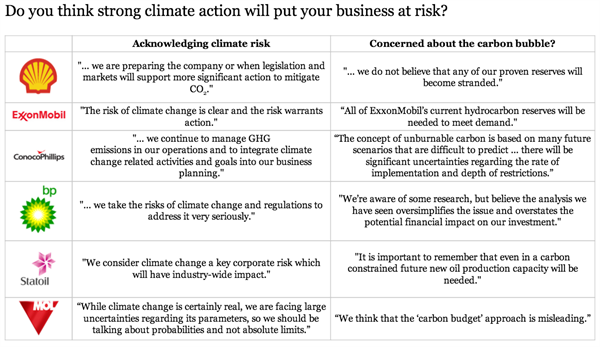

While we weren’t particularly optimistic that they’d want to talk about it, we asked oil, gas and coal companies for their take on the carbon bubble research. Many didn’t respond. But some of the bigger companies did, acknowledging that while strong climate action could affect their activities, none of them considered it a threat to their business this century.

Responses

We contacted 76 oil, gas and coal companies, drawn from the main trade groups. Seven companies provided substantial responses. 58 companies didn’t respond. We got no response from the coal industry.

Of the substantial responses, six came from major oil companies on the Fortune 500 list of the world’s largest businesses, and followed a similar formula.

BP, Shell, ExxonMobil, ConocoPhillips, Statoil, and MOL all acknowledged climate change was real, and that climate policy posed a risk to their businesses – to an extent. They agreed that regulations to curb greenhouse gas emissions should become more stringent over time, and probably will.

But none of the companies we asked saw climate action as a threat to their business in the coming decades – or if they did, they weren’t prepared to share that assessment with us.

BP said:

“We’re aware of [the carbon bubble research], but believe the analysis we have seen oversimplifies the issue and overstates the potential financial impact on our investments. However, we take the risks of climate change and regulations to address it very seriously, and take multiple steps to ensure that we understand and manage those risks effectively.”

Norwegian firm Statoil told us:

“The importance of human activities on global climate change is well documented by science. Statoil is concerned with the challenge of climate change, both in terms of the serious environmental implications and in terms of the impact this challenge will have on our industry. Climate change has drawn considerable management attention in recent years, and we expect this situation to continue as science develops further and as political responses continue to be matured and implemented at both national and international levels.

We consider climate change a key corporate risk which will have industry-wide impact. The issue is treated in a systematic way in our management and risk system … All in all we consider our portfolio of assets to be fairly robust with respect to future climate regulations and their market implications … It is important to remember that even in a carbon constrained future new oil production capacity will be needed.”

ConocoPhillips, the world’s largest exploration and production company, said it:

“… recognizes that human activity, including the burning of fossil fuels, is contributing to increased concentrations of greenhouse gases (GHG) in the atmosphere that can lead to adverse changes in global climate. While uncertainties remain, we continue to manage GHG emissions in our operations and to integrate climate change related activities and goals into our business planning … The concept of unburnable carbon is based on many future scenarios that are difficult to predict.

As additional policies are developed to limit GHG emissions, there will be significant uncertainties regarding the rate of implementation and depth of restrictions. Historically, climate change and energy policy development has been a long and complex process.”

Hungarian company MOL was more forthright:

“We think that the “carbon budget” approach is misleading. While climate change is certainly real, we are facing large uncertainties regarding its parameters, so we should be talking about probabilities and not absolute limits. In this vein, given the limits on our technologies and political realities, we expect that global carbon emission will exceed the level that is currently estimated to give a 50 per cent chance of staying below 2 degrees warming.”

Shell and ExxonMobil both pointed us to statements they’d previously made in response to Carbon Tracker’s research.

In March, ExxonMobil released a report to shareholders addressing the argument. It said:

“ExxonMobil makes long-term investment decisions based in part on our rigorous, comprehensive annual analysis of the global outlook for energy … For several years, [we have] explicitly accounted for the prospect of policies regulating greenhouse gas emissions (GHG). This factor, among many others, has informed investments decisions that have led ExxonMobil to become the leading producer of cleaner-burning natural gas in the United States, for example.

Based on this analysis, we are confident that none of our hydrocarbon reserves are now or will become “stranded.” We believe producing these assets is essential to meeting growing energy demand worldwide, and in preventing consumers – especially those in the least developed and most vulnerable economies – from themselves becoming stranded in the global pursuit of higher living standards and greater economic opportunity.”

Two months later, Shell sent a similar letter to its shareholders. The letter said “Shell believes that the risks from climate change will continue to rise up the public and political agenda” and that a “change in regulatory priorities could well be relatively sudden”. However, it adds that:

“… because of the long-lived nature of the infrastructure and many assets in the energy system, any transformation will inevitably take decades. This is in addition to the growth on energy demand that will likely continue until mid-century, and possibly beyond. The world will continue to need oil and gas for many decades to come, supporting both demand, and oil and gas prices. As such, we do not believe that any of our proven reserves will become stranded.”

The table below summarises the companies’ responses, either as they were sent to us or as they appear in the documents we were directed to:

Smaller companies

We also got short responses from 11 smaller oil and gas companies, saying they had some knowledge of the carbon bubble argument but didn’t believe it was relevant to their business.

Cameroon and Kenya based oil company Bowleven said that it wasn’t concerned because its reserves had already been “earmarked for near term industrial use”. Meanwhile international exploration and production company Hess said it believes “markets are pricing carbon intensive assets rationally”, so it doesn’t need to worry.

Others, such as Genel, operating in the Middle East, said they simply “do not believe that there is a significant risk to our operations from future legislation” without giving a specific reason.

In contrast, some companies pointed us towards their investments in cleaner forms of energy. E.On’s oil and gas wing pointed us towards the group’s renewables investments. The US’s second largest gas producer, Chesapeake, referred us to a spokesperson for trade body, America’s Natural Gas Alliance, who promptly highlighted the industry’s efforts to encourage consumers to switch to natural gas from more-polluting coal.

Offshore oil company Ophir declined to comment on the basis that it risked giving us commercially sensitive information. The rest of the respondees either declined to comment or directed us to the ‘climate change’ sections of their corporate sustainability reports.

Most companies simply didn’t respond. This included major companies such as Anglo American, Total, Rio Tinto, Repsol, Petronas, Marathon, and Peabody.

Visions of the future

Carbon Tracker argues that although companies’ currently known reserves may not be immediately threatened, their continued pursuit of new fossil fuel resources puts future assets at risk.

In a report released today, the organisation says despite Shell’s assurances, their business is at “a progressively greater risk” each year it invests in fossil fuel exploration and extraction.

It urges companies to analyse and declare how much of its business is at risk based not today’s assets, but those it expects to accrue in the future. Otherwise, companies’ assessments are “short-sighted”, it argues.

Couching climate action in terms of financial risk is meant to bridge a divide between policymakers calling for climate action and accountants concerned with energy corporations’ bottom lines.

But while the framing has clearly made some companies to take notice, it doesn’t appear to have made any of them feel threatened by the spectre of strong climate action. Or at least, if it has, they aren’t admitting it publicly.

Source: The Carbon Brief. Reproduced with permission.