A new analysis from the International Energy Agency has highlighted the growing importance of energy efficiency – in decarbonising energy markets, reducing emissions, aiding economic growth and supporting energy and international security.

The growing importance of energy efficiency as a hidden fuel (also known as Negawatts, or measured on the fuel not used) is being recognised as the amount of money invested in energy efficiency topped $US300 million in 2011 – equal to all investments in coal, oil and gas power generation.

Now, the IEA, says, there is an increasing recognition of its role as the “first fuel”. So much so that the energy use avoided by IEA member countries in 2010 was larger than actual demand met by any other single supply-side resource, including oil, gas, coal and electricity.

Yet, the market for energy efficiency has barely scratched the surface. If it was used to its potential, it could boost cumulative economic output through 2035 by $18US trillion.

The IEA says however that two thirds of the benefits of energy efficiency may go untapped unless policies change.

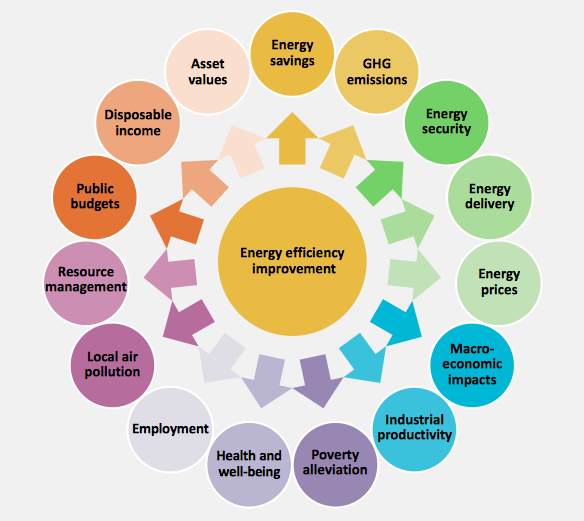

The IEA notes that the broader impacts of energy efficiency (highlighted in graph to the right) have not been systematically assessed, and the degree to which energy efficiency could enhance economic and social development is not well understood. It is often not considered at all in policy decision making processes.

The IEA notes that the broader impacts of energy efficiency (highlighted in graph to the right) have not been systematically assessed, and the degree to which energy efficiency could enhance economic and social development is not well understood. It is often not considered at all in policy decision making processes.

This is true of Australia, where state governments such as Victoria have sought to cancel energy efficiency schemes – despite the fact that data shows they bring enormous benefits. But often they are only considered for their impact on demand, and on the profits of coal fired generators.

IEA says its new study, Capturing the Multiple Benefits of Energy Efficiency, challenges the assumption that the broader benefits of energy efficiency cannot be quantified.

It shows, for instance, that when the value of productivity and operational benefits to industrial companies were integrated into their traditional internal rate of return calculations, the payback period for energy efficiency measures dropped from 4.2 to 1.9 years.

Another example comes in the residential sector: by making homes warmer, drier and healthier, energy efficiency measures can dramatically improve health and well-being. When monetised, for example through the cost of medical care or innovative metrics such as the value of lost work time or child care costs caused by illness, these benefits can boost returns to as much as four dollars for every one dollar invested.

“This report lays out the case for governments to invest more time in measuring the impacts of energy efficiency policies, to improve understanding of their role in boosting economic and social development and to facilitate policy design that maximises the benefits prioritised by each country,” said IEA Executive Director Maria van der Hoeven.