Earlier this week, the satirical website The Shovel had this amusing headline: Abbott commits to cutting Australia’s reputation by 30 per cent by 2015. It could well be Abbott’s most ambitious climate goal yet, and he’s probably already achieved it.

Australia’s about-face and isolation on climate issues has been evident to the world since early in his term as prime minister, from the moment that delegates in Warsaw began wondering “what the hell is going on down there”, as the Australian delegation turned previously held principles on their head.

It has been evident at the CHOGM summit, where Abbott sided with Canada in not wanting to contribute to the UN fund helping poorer nations, and in his visit to Canadian PM Stephen Harper, where their status as joint leaders of the climate Opposition was reinforced.

Abbott’s meeting overnight with Barack Obama simply underlined the point. According to the Huffington Post, White House spokesman Jay Carney said the two leaders did discuss climate change in their private session and that Obama emphasized the need for countries to adopt “ambitious domestic climate policies as the basis of a strong international response.”

He also said Obama believes climate change should be discussed in November’s G20 meeting, something that Abbott has resisted so far.

The key word here was “ambition”. In Abbott’s case, it doesn’t even extend to wanting climate on the agenda of heads of state at the G20, or to accepting an invitation to discuss the issue at a special meeting hosted by the UN. It certainly doesn’t extend to domestic policies.

Much has been written about the politics of Abbott’s position, but what of the economics? Abbott insists he doesn’t want the Australian economy “clobbered” by efforts to cut emissions. But what if the “clobbering” came from failing to do so?

Nat Bullard, from the increasingly influential Bloomberg New Energy Finance, gave a fascinating insight in a presentation in Sydney on Thursday, which underlines some of the global clean energy trends that the Abbott government and their conservative boosters in the media commentariat are trying to ignore.

Germany is not going to reverse course

The first of these is that Germany – the strongest economy in Europe – is committed to its “Energiewende”, or energy transition, and is not about change course – no matter how much the conservative press in Australia and overseas want to write it off and urge a return to nuclear and fossil fuel base load.

This graph below illustrates the anticipated growth in solar and renewables over the next few years. And while Germany is tinkering with its tariffs, it still has a target of 60 per cent renewables by 2035.

Bullard’s point is that what Germany did, others are now doing. Which is not to say that countries have to repeat its cost structures, or that they need to, because Germany was essentially a loss leader that brought down the cost of technologies. “The costs (now) aren’t significant at all,” he says. In many markets the investments are in the money right away, and less risky than many competing energy/infrastructure investments. “We now have an example of market transformation to look to.”

China’s rapid change

The second graph is another that suggests how quickly things are changing in China, the world’s biggest polluter and second biggest economy, and a major customer for Australian coal.

The second graph is another that suggests how quickly things are changing in China, the world’s biggest polluter and second biggest economy, and a major customer for Australian coal.

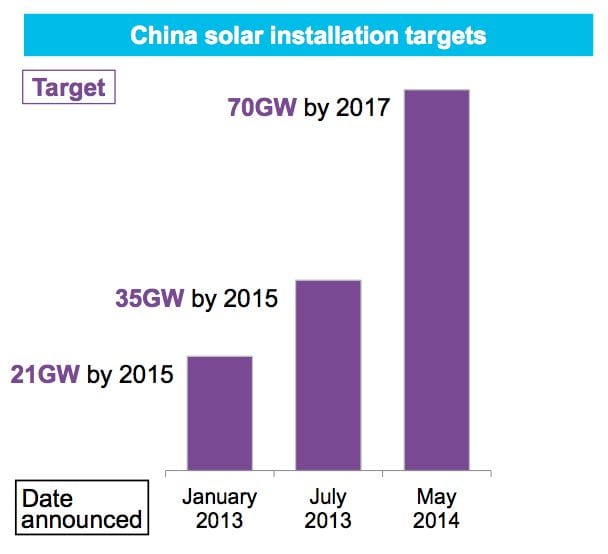

This graph highlights the evolution of China’s solar installation targets over just the last 18 months, and how quickly the country’s administration has increased its ambition.

The target has jumped from 21GW in 2015, to 70GW by 2017. By that time, Bullard suggests, China will also have 140GW of wind capacity – with both growing quickly.

Here is another graph that Bullard says is crucial to understand, one that illustrates how China is opening its energy markets to private investment.

Here is another graph that Bullard says is crucial to understand, one that illustrates how China is opening its energy markets to private investment.

“This is potentially quite a big deal”, he says. It will likely see a recalibration of tariffs, and could pave the way for new business models.

The US experience

This leads us to the US. One common factor from the US and the China experience is that both administrations are agitating to force out ageing and dirty generation. In Australia, the government seems certain to reduce its renewable energy targets after buying the argument that the policy should not seek to hasten the exit of incumbent generators.

California, the world’s eighth biggest economy, is looking to increase its renewable energy target to 40 per cent by 2020, Warren Buffett is looking to double his investment in renewables. Australia, meanwhile, stands to become the first country to dump its carbon price, and the first country to reduce the scope of its renewables target.

Jobs and business models

Bullard also notes that all of the energy jobs emerging in the US are in distributed generation. Which reinforces an assessment by economist Paul Klugman who said coal represents a fraction of on per cent of GDP.

Changing business models is again a big theme, hastened by distributed generation, and software. Google and Apple are to enter the market, and this will have a big impact on incumbents, as will the emergence of battery storage.

“The business model is going to be more fascinating than the technology,” Bullard says. “Will it sit in front of the meter or behind the meter?”

He says utilities probably had an opportunity early on to invest on the assumption that there will be a lot of distributed generation, but instead they ignored it, and have now sacrificed their advantage. “They thought it was small and inefficient and only weirdos would want it. Now everyone has it, and the utilities are wondering where all the money that they were going to get has gone.” Australia, because of its high penetration of rooftop solar, could be at the forefront of these developments.

Divestment and the flow of capital

And then there is the flow of capital. A lot of noise has been made about the so-called “divestment” campaigns, and the “carbon budget” warnings coming from high financial places. A lot of this has focused on university endowment funds, where the message – if it is wrong to pollute the planet, then it is wrong to profit from that pollution – resonates with youth. Bullard warns that fossil fuel divestment is likely to happen quickly, given the power of the internet.

A recent decision by Stanford University to quit fossil fuel investments is likely to be crucial. For a start, it puts pressure on other Ivy League universities such as Harvard to do the same, and reverse their recent refusal. The second point is that Sanford simply pointed out that they didn’t need coal stocks any more because there was a viable alternative. “This is a very simple statement, and a very economic statement,” Bullard notes. “It’s not a firebrand statement, it’s just assesses the issue on a pure risk basis.”

And what happens to investors who divest? HSBC gives some insight into that. In a new report released overnight, HSBC notes that its “climate theme” – essentially those stocks focused on carbon abatement and energy efficiency – has outperformed the main global benchmark, the MSCI All Country World Index, with a 6.7 per cent gain for the year, compared to 4.4 per cent.

That continues an outperformance of similar proportions over 2013, a rebound from the post GFC, post Copenhagen pessimism, worsened by the oversupply in the global solar market.

That continues an outperformance of similar proportions over 2013, a rebound from the post GFC, post Copenhagen pessimism, worsened by the oversupply in the global solar market.

“It clearly demonstrates investors’ growing appetite for the climate theme in 2014.” HSBC notes. (HSBC is one of a number of banks that has said it will not fund the development of the Abbot Point coal terminal in the Great Barrier Reef).

What’s more, it notes, the over performance has been delivered at proportionately lower risk. In short, it is becoming a solid, reliable and profitable investment. Low carbon energy production leads the way, with a 12 per cent return in year to date, with wind up 33.7 per cent, and hydro/geothermal/marine up 17.7 per cent.

No need, though, to check your Australian portfolios. There are no Australian stock figures in HSBC’s index. And Australian clean-tech stocks, stranded by policy uncertainty, have fallen behind the main benchmark (down 3.2 per cent in last quarter compared to 1.6 per cent gain), according to the local ACT Cleantech Index.

So, what does all this mean? Funds move and capital finds a new home. Increasingly, investors are finding it safe and smart to divert away from high carbon investments, and high carbon economies. The implications for Australia could not be more obvious.