The Australian government’s main economic advisor has significantly revised its cost estimates for leading energy technologies in an update that should introduce a dose of reality to the energy debate in this country.

The Bureau of Resource and Energy Economics quietly released an update of its Australian Energy Technology Assessment in December. The first report came out in July, 2012.

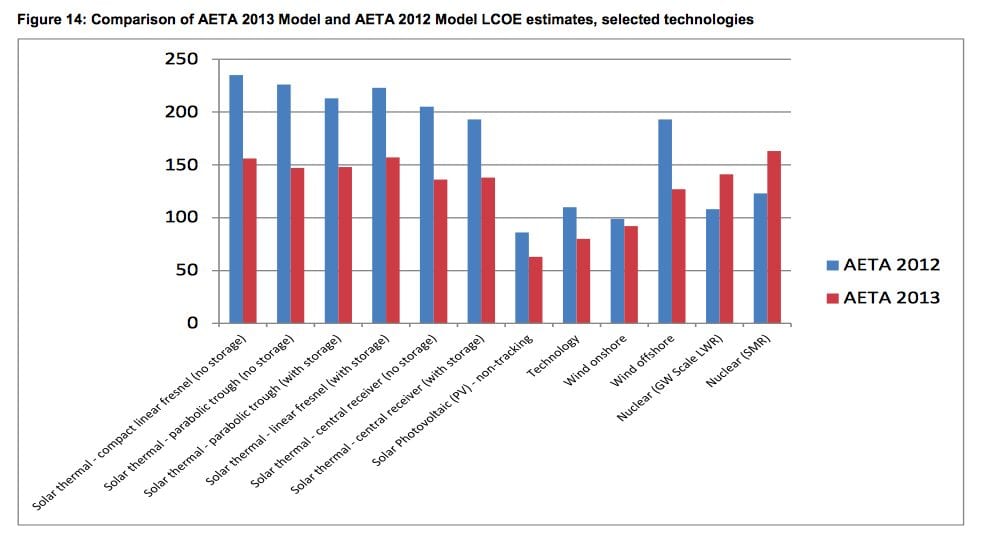

In the latest report – concluded after “consultation” with various industry sectors – the cost of solar technologies has been revised downwards (in some cases by up to 30 per cent), in particular solar thermal with storage, while the costs of clean energy rival technologies such as carbon capture and storage and nuclear have been revised upwards.

It leaves no doubt which is the cheapest avenue forward for Australia in a low carbon world – renewables, and solar in particular. Importantly, even if carbon emissions and their costs were not taken into account, it will still be the cheapest option.

This graph immediately below highlights the changes made by BREE for its energy cost estimates. It is for median LCOE (levelled cost of energy) estimates of various technologies in 2050 – the blue lines represent last year’s estimates, the red lines the latest revisions. Note how cheap solar PV will be. (The adjoining bar should read Solar PV – single axis tracking technology).

Indeed, the report recognizes that onshore wind energy is already cheaper than new build fossil fuels. BREE likes to frame the future by suggesting wind and solar will be cheaper on average than fossil fuels by the mid-2030s – but its graphs (the key ones are reproduced at bottom of this article) are clear – by 2020, the lowest cost wind and solar installations (which are already being achieved overseas) will be cheaper than the lowest cost coal and gas (even without pricing carbon).

Significantly, the revised report also flags that the best solar thermal with storage will be below $100/MWh. This is significant – it is way cheaper than other “dispatchable” sources such as peaking gas generation. And cleaner too.

The new solar power towers with storage that are about to be commissioned in the US, and are being considered in Australia, could redefine the energy debate in those countries with the appropriate solar resource – and answer the question about dispatchability and storage.

AETA’s original estimates on the cost of nuclear were laughable, given real world experiences international. We said so at the time and this was confirmed by the recent deal struck by the UK government for its first nuclear plant in more than two decades. (That price was £92.50/MWh, or $A170/MWh at current exchange rates. AETA originally suggested the cost of nuclear would be below $100/MWh).

Getting the LCOE right – or at least improving on the previous effort – is critical because the energy debate is high-jacked in this country by those who either don’t or should know better, and will be critical as the country makes important decisions for the future in its review of the renewable energy target and the preparation of a new energy white paper.

The conservative state and federal governments consistently brand renewables as expensive, when clearly they are not (although some state-based support schemes were way costlier than they needed to be because of mismanagement).

Nuclear boosters – who have some sympathy within the current government – have also taken the opportunity to assert that “nuclear is cheap” – a slogan the AETA accepted in its first report with little critical analysis. Some of its most prominent hoorayers have used the CSIRO e-future modeling – which featured the absurdly low nuclear estimates – to boost their case.

AETA has at least partially rectified its errors by lifting its estimates of the capital costs of nuclear by around 50 per cent – it will be interesting to see how quickly CSIRO amends its own modeling.

However, the nuclear picture is still not complete because AETA has refused to include the insurance and decommissioning costs of nuclear on the basis that it does not do so for the 40 other technologies. Well, that’s because other technologies do not have the same issues on either front.

The cost estimates for carbon capture and storage were also significantly increased after AETA admitted it had “overlooked” the well-accepted fact that adding CCS greatly reduces the thermal efficiency of the coal-fired generators. i.e. it needs to burn more coal to produce the same amount of electricity. All this does is confirm that fossil fuels with CCS are simply not in the money.

But the AETA assessment stills fall short on many fronts because the LCOE calculations do not include interest costs – which in the case of nuclear are significant because of the sheer scale of the capital investment, and the time it takes to construct them. (It’s a bit like buying a house and not worrying about the mortgage).

It also does not include variations for fuel costs (such as what happens when gas prices soar, as they are already starting to do in Queensland).

Part of the reason for the reduced cost of solar PV and solar thermal was a more informed appraisal of the operations and maintenance costs (they were reduced up to 27 per cent in the former and up to 30 per cent in the latter), and the recognition that solar has a much faster capital learning rate.

Still, there is also a suspicion that BREE has a level of bias against renewable technologies in favour of the traditional baseload installations.

For instance, it notes:

“To cater for sudden, unpredictable, changes in the output of variable power plants, it is necessary to operate responsive, dispatchable power plants (e.g. hydro, open-cycle gas turbines) in a back-up role to maintain the overall reliability of the electricity system. As a result, LCOE by technology is not the only factor considered when deciding what type of electricity generation plant to construct.”

There is no mention of the fact that most of these dispatchable power plants already exist because they are needed to back-up “baseload” generation, to cater for sudden changes in demand and to support unexpected outages. The fact that South Australia now has more than 31 per cent “variable generation” from wind and solar without the need for any new “back-up”, should put those comments into context.

Here are some of the forecast graphs. You can click on these to expand them. These and others (for 2030 and 2050) can be found at the BREE website.