Iain MacGill is the first to admit that there’s a good deal more research and modelling work that could be done before Australia might confidently launch itself on the path to 100 per cent renewable electricity generation.

But the main, and very positive, message from the UNSW Associate Professor, and joint director of its Centre for Energy and Environmental Markets (CEEM), is that on the basis of current research and modelling, the viability of a shift to a 100% renewable energy network looks “very promising” – in fact, when you factor in the costs of business-as-usual, it’s likely to be cheaper than continuing on the current path.

Speaking at the All-Energy Australia conference in Melbourne today, MacGill outlined some of the preliminary findings of the current UNSW project on the technical feasibility, underlying economics and possible commercial implications of 100 per cent renewable energy generation for the Australian National Electricity Market.

It’s a hugely complex task, that has had to factor in such technicalities as the NEM’s 0.002 per cent unserved energy standard, moderate energy spill, moderate total biomass, no extra hydro capacity, the need for new NEM regions, and the perennial question of whether a 100 renewables mix using highly variable and somewhat unpredictable solar and wind can reliably meet demand at all times and locations.

And then, of course, there is the all-important question of whether 100% renewables is economically worth doing, not to mention commercially feasible: can we establish commercial frameworks that drive appropriate deployment at the speed and scale required?

The final estimates for the UNSW work are not ready for release, but when they are they will form a crucial reference point for the clean energy industry. One of the criticisms of the detailed work that the Australian Energy Market Operator is being asked to undertake into 100 per cent renewable scenarios is that it will not reference its cost estimates to business-as-usual, or to the potential savings.

As the International Energy Agency noted in its recent assessment on the effort required to transform the global energy grid to meet a 2°C global warming scenario, this may require a capital cost investment of $36 trillion over BAU – but this will likely to pay itself back by 2025 in fossil fuel savings, and generate total savings of $100 trillion by 2050.

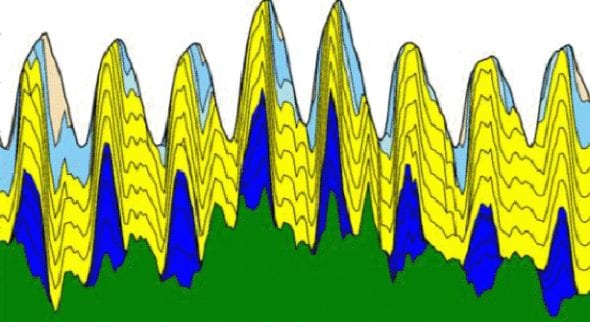

And as MacGill today pointed out (and illustrated in the charts below), if the inevitable replacement of existing ageing fossil-fuel power plants – the majority of which would be 30 years and older in 2030 (and things look particularly grim on this front for Victoria and NSW and Queensland, as you can see in the graph below) – is factored in to the Australian equation, then the cost of 100 per cent renewables starts to look very competitive compared to that of business-as-usual.

At a carbon price of $50-$100/tonne, MacGill told the conference, if you rebuild all of those plants and then paid the carbon price, “it would cost more than replacing them with 100 per cent renewable energy sources.”

And while he admitted that a carbon price at such levels might seem unrealistic, considering the current state of the market, MacGill points to the IEA’s recent projections of how much higher again the carbon price would need to be in a worst-case scenario, if the world didn’t do enough, quickly enough, to cut emissions.

As the charts above reiterate, these are preliminary findings only, and the economic costs are modelled the AETA’s 2012 BREE report, which MacGill repeatedly stressed were “not right.” If you’re going to compare the costs of renewables to business as usual, he told the conference, it needs to be a fair comparison.

So 100 per cent renewables is looking promising technically (the UNSW modelling only factors in currently available resources and technologies, and no extra hydro – you can see the mix in the charts above) and economically. But what about the commercial feasibility? According to Macgill, this is where the right policy becomes all-important – and where, in Australia, “much more progress is required.”

On this point, he refers to the IEA’s view on global clean energy progress and what’s required from policy to protect the climate, as expressed in its Energy Technology Perspectives, 2012 report, which said: “Continued policy support needed to bring down costs to competitive levels and to prompt deployment to more countries with high natural resource potential.” And “Large-scale RD&D efforts to advance less mature technologies with high potential.”