The UK government has just announced a target of a 78% reduction in the country’s emissions by the year 2035, effectively bringing forward its previous 2050 target by 15 years.

This is the first of many similar headlines you’ll be seeing this week. The ‘Earth Day’ climate summit due at the end of this week, convened by President Joe Biden of the United States, will see a range of different countries announcing upgraded climate ambitions.

The UK government target is a pointedly ambitious one. The number comes from a major report released last year by the country’s “Climate Change Committee (CCC)”, an independent government advisory body tasked with guiding the government’s trajectory to net zero by 2050. The target is enshrined in legislation, and has been upgraded to include emissions from international aviation and shipping, a significant proportion of the country’s emissions.

Setting the UK's Sixth Carbon Budget (2033-37) in law is a huge moment. A 78% reduction in territorial emissions between 1990 and 2035.

Until 2019 the UK's 2050 target was an 80% reduction. It has effectively been brought forward by 15 years.

That's the implication of #NetZero. pic.twitter.com/1UkI8YXDFt

— Chris Stark (@StarkClimate) April 20, 2021

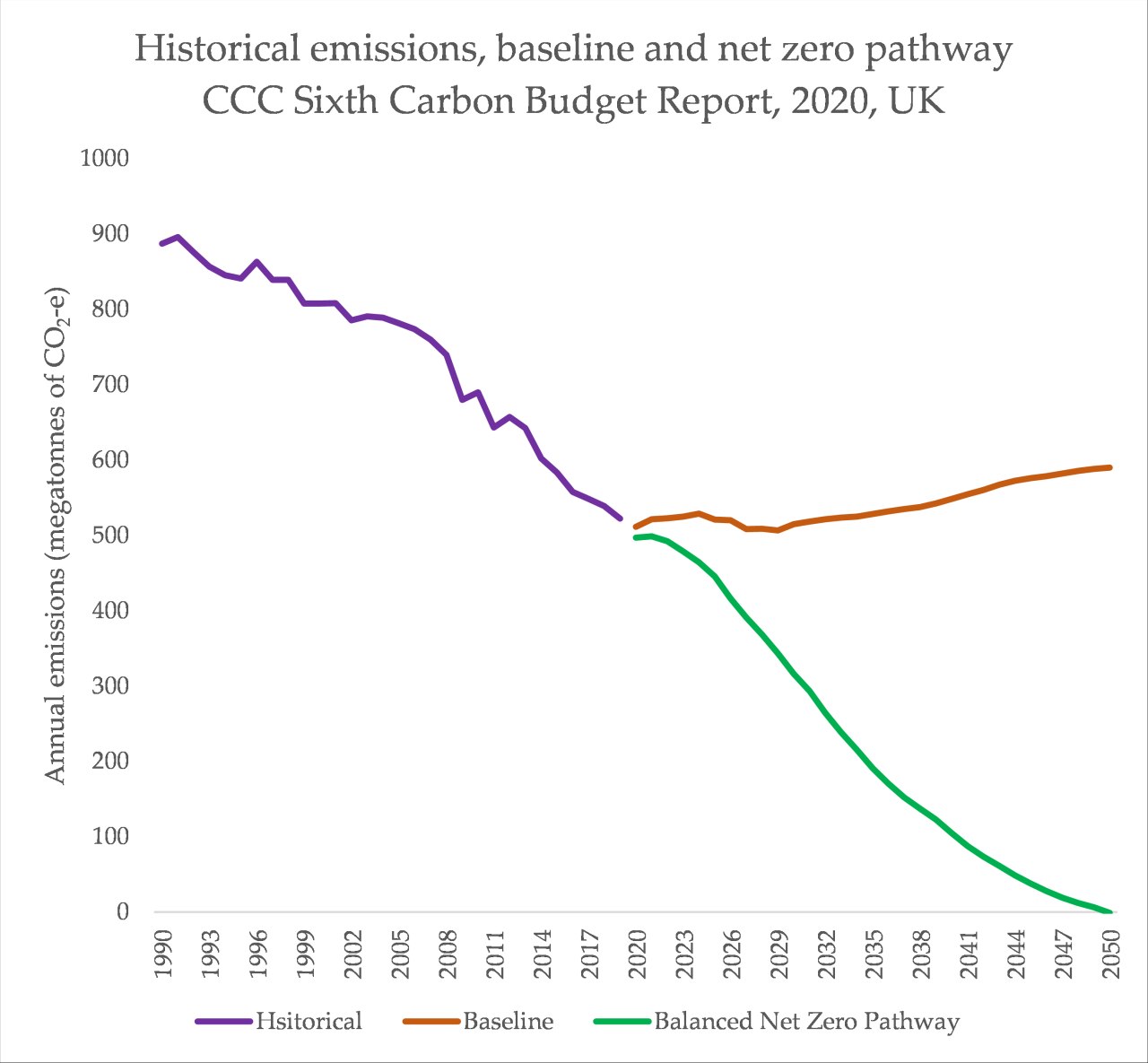

The CCC’s sixth carbon budget report (6CB) outlined a clear pathway from current emissions to net zero, detailing the significant changes that must occur across a range of sectors, and including a collection of related scenarios. The report shows that to be on track for net zero by 2050, the UK must reduce emissions by at least 78% by the year 2035, extending and sustaining the current level of emissions reductions across the entire economy.

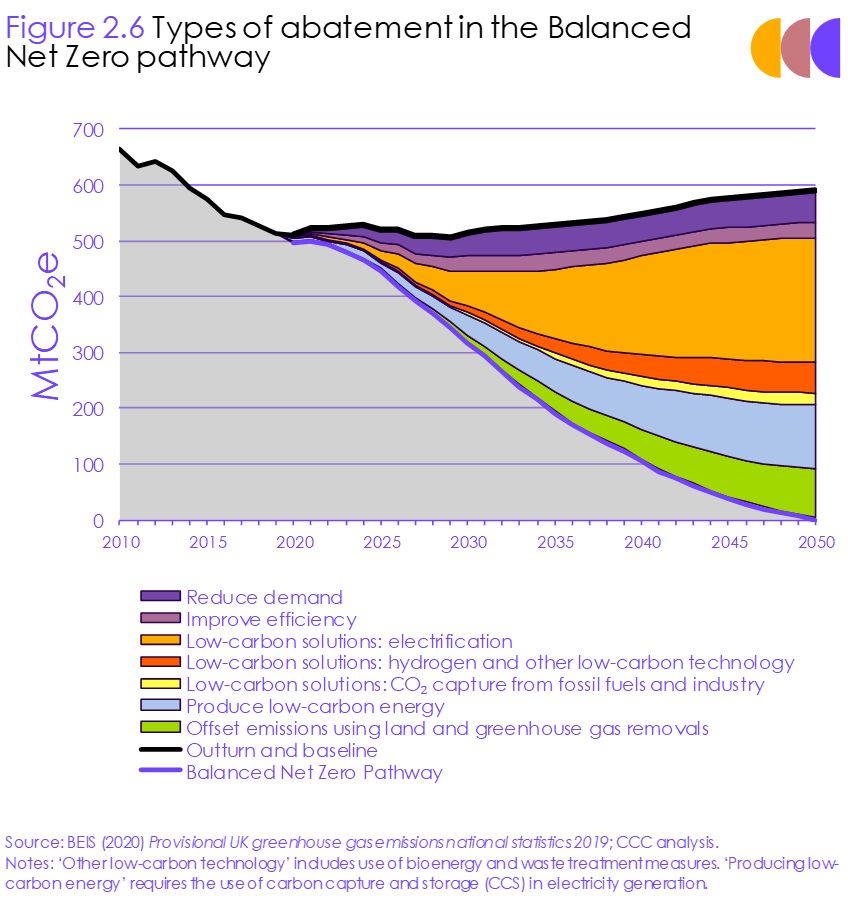

Previous reductions have come from increased energy efficiency and the phase-out of coal, but future emissions reductions will come from electrifying transport, heating and industry, ending fossil fuel usage by 2035 and implementing carbon capture and carbon removal for residual emissions.

While the adoption of the target has been welcomed, several UK energy experts and analysts have highlighted that detailed and effective policy must follow, particularly focused on the transport and residential heating sectors. This will be particularly challenging, but the UK’s Prime Minister, Boris Johnson, is expected to announce a range of new policies in the lead up to the 26th Conference of Parties meeting to be held in Glasgow at the end of this year.

The UK is committing to cut its emissions to 78% below 1990 levels by 2035, including international aviation & shipping

The target is a step change vs earlier carbon budgets

But govt projections show there's a huge gap between ambition + deliveryhttps://t.co/6mmqqcOOWY pic.twitter.com/Hx7vaVoMnr

— Simon Evans (@DrSimEvans) April 20, 2021

In announcing their target, the UK government also somewhat distanced themselves from the CCC’s 6CB report. “The government will look to meet this reduction target through investing and capitalising on new green technologies and innovation, whilst maintaining people’s freedom of choice, including on their diet”, said the Johnson government. In the CCC’s 6CB modelling exercise, diet changes account for 10MTCO2-e of emissions reductions (of 52 MTCO2-e abated in total) in the year 2050, but 35MTCO2-e of ‘residual’ emissions remain.

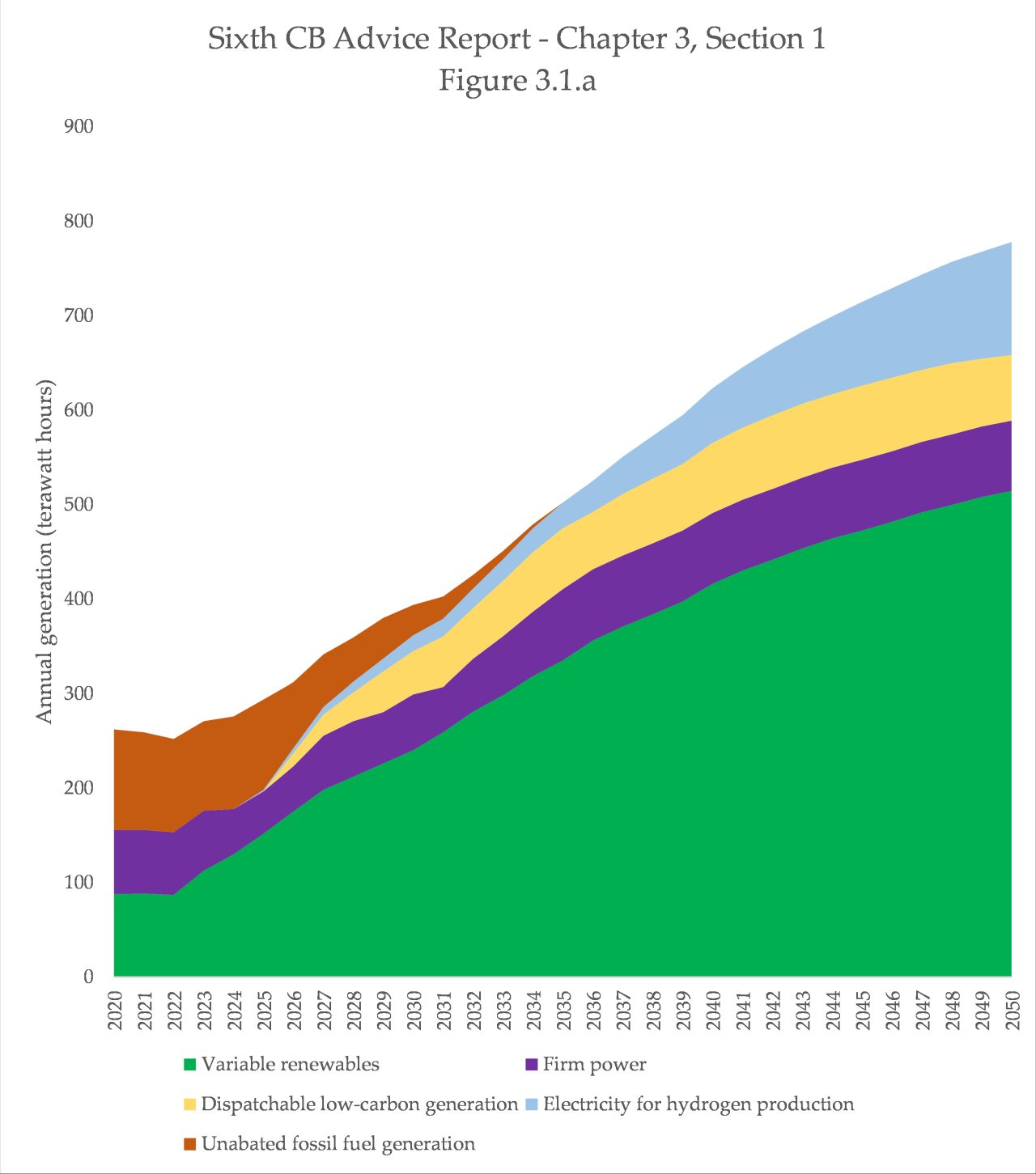

In the power sector, significant change has already occurred. Coal has been functionally removed from the UK’s power system, save for occasional activations. This means the pathway for full grid decarbonisation is a matter of either shutting down gas-fired power or allowing only gas-fired power stations equipped with carbon capture; something which features in the CCC’s modelling (“dispatchable low carbon generation” includes gas with CCS, bioenergy with carbon capture and storage, and ‘firm power’ includes nuclear).

For the transport sector, a major transformation must occur very rapidly. The UK has announced a plan to fully phase out the sale of fossil vehicles by 2030, but the 2050 trajectory must see significant growth in various modes of emissions reductions in transport, including EVs, prior to 2030. Demand reductions also play a major role, in the CCC’s modelling.

The Johnson government’s climate targets are ambitious, cemented into legislation, operating on a short timeframe with clear accountability, but the policies tend to be focused on technology and business, with economy-wide considerations of jobs, benefits, costs and social justice and equity issues not featuring strongly.

This adds another layer of pressure onto the Morrison government. The UK’s baseline is the year 1990, but to compare this target to Australia and set both at a 2005 baseline, it is the equivalent of updating the current 26-28% target to 60%, and a target of 76% by 2035. Recall the half-year furore around the Labor opposition’s suggestion of a target of 45% by 2030, and you’ll know how improbable any such change is from Australia’s current government.

The UK’s climate policies are not without their problems, but the fundamental structure of climate policy is significantly removed from Australia’s current situation. Mutterings of “preferences” for net zero are essentially meaningless compared to a structured, accountable trajectory towards net zero, and an independent body providing clear advice on how to achieve those reductions.

It won’t be the first embarrassment on the global stage for Australia this week, but it’s a significant and serious one.